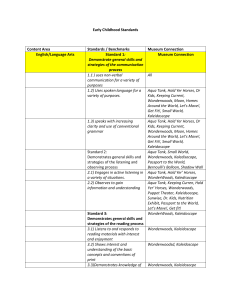

Kaleidoscope: Building an Arts Infused Elementary Curriculum

advertisement

Arts and Young Children Kaleidoscope: Building an Arts Infused Elementary Curriculum by Dr. N. Carlotta Parr, Indiana State Arts Consultant Dr. Jan Radford, Michigan City Area Schools Administrative Assistant for Curriculum & Instruction, and Dr. Susan Snyder, Scholar-in-Residence, Connecticut State Department of Education ABSTRACT Michigan City Area Schools received a school improvement grant and used the challenge to develop an arts-integrated program in eight struggling schools. The goals of the Kaleidoscope Program were to improve language and math scores; foster collaborations between faculty members and the community; build multicultural understanding; and utilize a multiple intelligences perspective to observe, teach and assess students. Three individuals representing the perspectives of district, state and outside consultant shared leadership to facilitate the change process. The program evolved over time, and led to changes in attitudes, teaching, and goals set for students; and ultimately toward significantly raised scores for four of the eight schools. In addition to the program’s quantitative success, less measurable outcomes were evident in teachers, students, and school communities. Documentation of this program provides additional support for the growing number of successes gained through arts-integrated curriculum planning. KEY WORDS integrated arts low achievement curriculum development collaboration change 1 INTRODUCTION Michigan City, Indiana is a small industrial city at the base of Lake Michigan. When several of the elementary schools’ test scores triggered state-funded reform, they embarked on a bold initiative to develop an arts infused curriculum that met the needs and interests of their student population. Under the direction of Jan Radford, the district was awarded a grant for a multi-layered school improvement plan encompassing four main goals: 1. To infuse the arts into language arts and math curricula, 2. To foster collaborations between classroom teachers, arts specialists, and the community; 3. To build greater multicultural connections and understanding; and 4. To use a multiple intelligences perspective to observe, teach and assess students. Eight schools participated in the Kaleidoscope program, and Jan was soon working with Carlotta Parr, State Consultant for Fine Arts. Together they began to mold a plan. Sue Snyder was hired as facilitator for the program, and the three worked together for a year, shaping and sharing a research-based vision to facilitate change. Here is the story of a most successful collaboration in Michigan City, told through the interwoven voices of Jan, Carlotta and Sue. BACKGROUND Jan: The Michigan City Areas Schools have been in a pattern of decline for the past ten to fifteen years in terms of enrollment, graduation rate, and standardized test scores. The lowest point for our district came in February, 1994, when ten of our sixteen schools were placed on probation by the Indiana Department of Education. This date was also the turning point. Sometimes what seems like an ending is the beginning of something new. For the Michigan City schools and community, probationary status served as a wake-up call that our students had been neglected. If the schools were to receive accreditation it would take the community and school personnel working together, not only harder but smarter. 2 Along with probationary status came state school improvement funds. We dove into the research on effective schools. We visited successful programs. We obtained high-quality professional development for our faculty and staff. We considered options that would enhance achievement for all our students. We implemented several new programs. The journey was difficult but exciting. Success was coming slowly but surely. While the trend from 1994-96 indicated improving test scores, some of our schools continued to qualify for school improvement funds. In 1996, eight of our schools qualified for ISTEP-UP (Indiana Statewide Testing for Educational Progress) dollars through the Educate Indiana Program. Even with the prior interventions, more than onehalf of these schools’ students did not yet meet the proficiency expectations for their grade level. We knew we had to search further to find new instructional strategies to meet the needs of our students. In order to create meaningful learning experiences for children, we focused our ISTEP-UP efforts on an experiential, program-based, thematic, integrated arts program called Kaleidoscope. This program enabled classroom teachers to collaborate with community artists as well as art, physical education and music educators to provide first-hand experiences and integrate various art forms into the curriculum. Kaleidoscope emphasized patterning in math, observation skills, and an appreciation for individual differences through arts-related language instruction. The rationale for this program was that students would be able to learn successfully and improve their selfesteem, because teachers would incorporate the visual, performing, and musical arts. These would continue to be taught for their own intrinsic value, but also be used as teaching tools which are not restricted by language barriers and socioeconomic backgrounds. Arts education research suggests that the arts: 1) help energize the school environment; 2) help students develop critical skills for life and work; 3) improve student performance in other subject areas; 4) expose students to a range of cultures and perspectives; and 5) can reach hard-to-reach students. The projected impact and benefits of the program included improving student performance, creating a new learning partnership between students and teachers, pulling additional adults/artists into the 3 learning community, and providing teachers with opportunities to gain insight into their students’ learning preferences and motivation. BEGINNINGS - THE GRANT APPLICATION & APPROVAL PROCESS The large number of students qualifying for remediation made Michigan City Area Schools eligible for the ISTEP-UP grant dollars. The approach they elected allowed them to gain both approval and additional grant dollars. Carlotta: The inclusion of the arts in Goal 3 of the National Goals held much promise for those concerned about arts education in American schools. There was hope that, at the least, arts education would be “valued” in the school curriculum. There was even more hope that there would be funds to support school arts programs. While there was money designated for national arts education standards, we (I) quickly realized that state funds to support arts education was not a “sure thing.” Each state can determine the parameters for their state plan. Indiana supported local decision-making by allowing individual applicants to devise their own plans. Linda Cornwell, Consultant for Education Indiana (Indiana’s Goals 2000 plan) and I had been talking about ways to get schools to include arts education in their grant applications. One solution we devised was for me to make a presentation at the statewide meeting to discuss the grant application. I was very pleased that four school corporations/ districts, including Michigan City, were interested in incorporating the arts in the local plan for school reform. Michigan City, however, had a vision even bigger than I had anticipated. Unbeknownst to me at the time, Jan Radford had been thinking about how to integrate the arts into the curriculum. Jan: Rather than propose giving our students more of the same, which obviously had not worked in the first place, we researched alternative approaches to improving students’ achievement in math and language arts. We did not believe a traditional before or after school remediation program would make a substantial impact. We knew that we needed to significantly alter the instruction we offered during the school day in order to reach our students and hook their interest. We also knew that in order to infuse arts 4 education into instructional practice we would need to offer intensive professional development and substantial support to our staff. The process of determining a program involved working with the building administrators, community artists, and the leadership of our local education association. Linda Rugg, the principal of Springfield Elementary, was particularly influential in promoting arts and providing research information. The actual writing of the proposal was largely the effort of one person, but with much interaction between the various stakeholders in order to use the proposal development to build the consensus process. We knew we were on the right track when a consultant from the Indiana Department of Education called to inform us of our approval with the side comment that we would get additional funds if there were any dollars available after the award process was complete! PLANNING THE KALEIDOSCOPE PROGRAM The ideal planning model includes all participants from the start. However, as this model emerged, the reality was quite different. “Visions are necessary for success… Vision emerges from, more than it precedes action. Even then it is always provisional ...Shared vision, which is essential for success, must evolve through the dynamic interaction of organizational members and leaders. This takes time and will not succeed unless the vision-building process is somewhat open-ended. Visions coming later does not mean that they are not worked on. Just the opposite. They are pursued more authentically while avoiding premature formalization.” (Fullan, 1993, p. 28) A series of events and needs led to the involvement of new participants as implementation evolved. Jan: The weakest link in our planning process was that classroom teachers and our art, physical education and music teachers were not in on the program development from day one, because the proposal was written after school closed for the summer. We did compensate for this in three ways. As soon as the program was approved, we worked with every participating school staff and the K-12 Curriculum Committees for art, music and physical education to make them aware of the overall program goals. Next, we established a district-wide focus team consisting of representative from every Kaleidoscope school in order to pool our ideas, programs, resources, and expertise. 5 Finally, we designed the program to enable each school to personalize the program to their students and school setting. Kaleidoscope, was chosen as the project’s name and a metaphor to reflect the unique nature of this program. Like a kaleidoscope, each of the schools shared common pieces, but had the flexibility to configure the pieces to meet their own vision or picture. Thus, the district level focus team provides the program’s framework of goals, objectives, and philosophy while the school teams personalize the program through their specific activities. We have also worked to inform the community of our efforts through school board presentations (which are carried on local cable access), local newspaper articles, and newsletters to parents and school community. Sue: By the time I became involved with Kaleidoscope, schools had already created goals and strategies for the year, and were in the process of implementation. The planning teams used their prior knowledge of integration, the arts, student interests and community/school needs to develop beginning steps. There had as yet been little dialogue between the arts teachers and classroom teachers, and the yearly plans relied heavily on artist-in-residence programs, assembly-type arts programs brought into the school for a period of time, and some field trips. Schools also made plans for extracurricular clubs and groups, as well as special days during the year which celebrated the arts. While this was a good and necessary start, it had a focus that was potentially damaging to the school-based arts educators and arts programs. The focus was to look outside the school for quick fix moments, rather than focusing inward on the richness of interactions to be found within each school. The emphasis needed to be put squarely back on education in, about, and through the arts, rather than entertainment from the arts. Only then would meaningful systemic change be possible. STAFF DEVELOPMENT Professional development was critical to the Kaleidoscope program, since student success was contingent upon teachers’ success in integrating arts into instructional practice. Teachers could not fundamentally alter the delivery of instruction without ongoing, high quality, sustained professional development that included reflections, guided practice, and support from the administration. The professional development plan was based upon the 6 national standards for staff development (National Association of Elementary School Principals, 1995). The professional development had several layers of support built in to enhance implementation and sustainability. Sue: After a brief initial contact by Carlotta, we began a series of conference calls to determine the scope of in-service for Kaleidoscope. The four main goals were in place, as well as the initial stages of implementation. A few main concerns were the definition of integrated learning, establishing communities of collaborators within schools, and creating an open environment for change while validating current efforts for the year. We were after a deeper understanding of arts integration than the usual “song about this” and “picture about that.” Rather, we hoped to move toward deeper integration that allowed the arts to be used for their inherent value as powerful modes of communication, and unique ways to know. The arts are highly motivating, and research had led the grant writers to seek this path. Yet, implementation could not be effective until an in-depth model was on the table. We needed to delineate the differences between teaching in, about, and through the arts. We needed to understand what arts curricula entailed. And we needed to identify links between the language arts and math curricula and the arts. Yet another goal was to look at perceptions of integration and compare them to sound theory. The in-service days were designed to provide information on integration theory, a perspective on arts and their role in education (particularly the four large objectives of Kaleidoscope), and a forum for decision-making in light of this information. In many ways this was a “chicken or egg” dilemma, because the yearly goals were already underway. While these plans were exciting and infused energy, money and enthusiasm into schools, they lacked the depth required to make sustained changes in teaching and learning. Each day of in-service was designed to allow ample time for interaction between participants, concise descriptions of theoretical concepts, and activities which helped teachers understand each other’s disciplines. Creating change is hard work, and the rigorous tasks of each day brought many questions along with the answers. Soon, teachers were engaged in high-level dialogue with a fresh openness that was sometimes 7 scary. While some dipped their toes in the waters of change, others jumped in and began to swim. Each found a tolerable level along the comfort/discomfort continuum, and began to progress. Jan: Beyond the traditional concept of “in-service” as staff development, the grant paid for substitute teachers, which afforded our teachers release time to plan as school teams or grade level teams with classroom and special area teachers together. As artists worked with our students or taught about art through “informances,” the teachers were partners with their students learning both about the arts, and new strategies to infuse art into education. An additional level of support occurred through discussion at monthly district-wide Kaleidoscope team meetings. Representatives of each Kaleidoscope school team met to share ideas, resources, ask questions, and gain support from one another. We have been diligent in our efforts to build a sense of “we” and empower staff to make decisions that enhance all students’ opportunity to learn. A THREE PHASE PROGRAM The in-service program was developed in three sequential segments. Phase I included two days of in-service for each group (Pre-K-3 and 4-8, with music, art and P. E. teachers as available; some community artists). These days were spent identifying the parameters of each school’s program, thinking, and interactions. Some theory was shared to provide a scaffolding for programs already in process, and to begin thinking toward deeper understanding. Model integrated arts activities were shared both to provide interactive experiences for the teachers, and to take back to their students. Sue: As I reflect, there were five main needs that drove the first in-service days. 1) There was a need to facilitate plans already in place, while creating an understanding and need for deeper and more organic integration. 2) The concept of integrated curriculum needed to develop from superficial understanding to a level which honored the integrity of disciplines, teachers and children. 3) The role of the arts specialists needed to change from marginal involvement to an integral position both in planning and implementation. Arts educators were at risk of having guest artists drive their programs, rather than those programs brought into the school providing support and enhancement of sequential arts 8 education the arts educators were providing students. There was also the danger of outside disciplines driving the arts programs, rather than building a curriculum that deepened understanding of both content areas. 4) The arts were defined in as many ways as there were participants, and we needed common vocabulary and definitions from which to work. 5) Teachers within and between schools knew what the goals were, but needed some fresh perspectives, strategies, materials and ideas to take back and share with colleagues and students. They also needed to develop collaborative, respectful and trusting relationships. Each of these situations and needs represented a challenge for our implementation team, because each required an element of change in the system and participants. After the two formal days, this phase continued informally as team members went back to each school for sharing, implementing, dialogue, and reflection. Phase II began with reports of progress, followed with a day of developing theory based on practice. Pre-K - 8 teachers were together on this day, and it was an intense inspection juxtaposing current practice and theoretical beliefs. The range of teacher experience, abilities, and creativity in the group afforded challenges at every turn. This pivotal day moved participants past the level of the known, and required skillful reflection and critical decision-making. Many heroes emerged this day, stepping past the precipice of comfort for the sake of real change. The participants’ reflections shed light on this complex and challenging process: The moment of break-through for me was realizing what true integration is. I didn’t discover it on my own. I was shown by some graphic organizer on the overhead. Sue demonstrated true integration at our second meeting. Then I understood how integration really should work. I always thought ‘I’ taught an integrated curriculum - now I know ‘I’ can’t do it alone. [I’m] starting to see the ways to tie in the various disciplines and work to establish links between subjects and to show the importance of the Arts with the academic areas. I found information on connection of steady beat and reading ability interesting. (There is some evidence that children who cannot keep the 9 steady beat have difficulty reading, and as beat competency improves, so does reading ability.) It was very important to have special teachers and classroom teachers at the workshops together. After the last workshop our team presented what we learned and worked on to the entire staff at an after school meeting. This was not the first time we presented Kaleidoscope, but the staff was still very frustrated. Most wanted to participate, but were very confused. If they didn’t want to participate they would have just let us talk, and then let it go. Even the music and PE teacher and I do not totally agree on what Kaleidoscope is. I believe that this is all right. Having a classroom teacher there seemed to help bridge the gap. Later I wrote a paper with just my feelings about Kaleidoscope to each of them. I let them know that it was my opinion only, not any one else’s. One point I brought up was that there was not one right answer, that the solution to the problem was up to us to discover as a school. After this many staff members came up with ideas (pieces of the puzzle). The significant experience I remember most about the Kaleidoscope workshops involves the discipline specific adaptations made for the theme and “big questions.” I felt as if numerous ideas, concepts, and plans became so clear and evident. The philosophy and theory now seemed so practical and useful for implementation. This was probably one of the best feelings I received from the workshops. True integration – more than just “here is a topic, please do an activity.” The planning it takes to do an integration [is much more than I realized]. The disciplines overlap and layer. I still teach my discipline as another teacher teaches his/hers. [I liked seeing] possibilities of teaching on a topic or idea when there is no time provided to communicate or plan with others. 10 Phase III focused around another single day in-service, when participants again shared their individual successes and challenges, then began planning for the following year. The plans they started were later taken back to their individual schools to be expanded and elaborated upon within the school setting. The participants then spent some time reflecting on the Kaleidoscope experience for themselves, their students, and their schools; using storyboards to graphically represent their progress. Karin McKenna described her reactions in an article published in the Michigan City News-Dispatch: What an amazing and wonderful thing it is when months of practice, learning and teamwork finally come together! Marsh School concluded a portion of its Kaleidoscope Program Monday night with a fun-filled and rousing production of ‘Motown at Marsh,’ followed by a school-wide writing fair. As only one of many teachers involved with this program, it is with great satisfaction that I step back and view months of integrated teaching pay off. Yes, what a great feeling to be part of an education program that works just as expected. For years, teachers of the arts have understood that organized, welldisciplined music, dance and art programs have residual benefits for students. However, not until the graphic evidence from recent brain/learning research was made available to the mainstream public could we point to proof. What a wonderful time period to be a “special” teacher in the educational arena! Monday night’s performance shows just how INCLUSIVE the arts can be. The following comments demonstrate the range of reactions and power of the process: At one early in-service workshop we did an activity during which teachers remembered an important arts-related moment from their own childhood. After picturing the moment in their mind’s eye, each created a torn construction paper image, shared it with others, then placed it in a paper “quilt.” The event I remember was when we made the quiet pieces with the construction paper. I enjoyed the experience of self-expression and I liked the idea of tearing the paper to achieve a more abstract look. It was very intriguing to observe the 11 quiet pieces of the other folks. I thought that activity was positive for teambuilding and to engage the mind. The mind-engaging activities that we have done have inspired me to be more aware of doing things in my classroom to engage the mind for learning. That particular expressive activity relates to storytelling, and the telling of one’s own story helps foster respect and lessen prejudice. One school used Kaleidoscope funds to bring in experts for a Puerto Rican Day celebration, including experiences with food, festivals and aspects of Puerto Rican culture. I chose to focus on our Taste of the Nations - Puerto Rican day. The kids, teachers and presenters had a wonderful experience learning, cooking and tasting. Everyone involved learned a great deal about the culture. [We became aware of] the similarities and differences between our culture and theirs and also the Puerto-Rican culture compared to the Mexican culture. Side note: The teachers liked it so well that some of us took a cooking class from our presenters! Now we eat Puerto-Rican food on a regular basis - Yum! A popular artist-in-residence was the Ballet Lady, who worked to help the children understand ballet through active participation. I really enjoyed how engaging the children were as they moved their bodies freely, along with the Ballet Lady. They went from being stiff to no inhibitions at all. They learned so much - French words, posture, self-control, different music, sharing . . . It was a wonderful experience. Storytelling was a favorite artist-in-residence activity, integrating all arts including language arts. The most exciting for me was the oral storytelling we had in my language arts classes where the leaders incorporated oral storytelling, music, mood, setting, rhythm and movement, word webbing, summarizing and retelling into the two day 12 lesson. The kids enjoyed it and so did I. The drama/acting really came out of some of the kids as they participated in the telling of ‘Wiley & the Hairy Man.’ During the in-service Sue guided several activities, including making lummi sticks and drums. Lummi sticks are used by both Northwest Native Americans and South Sea Island natives for coordination games and dances. Our lummi sticks were made of wrapped newspaper, decorated with Aboriginal dot-drawing inspired marker art, and coated with clear packing tape. Once made, they became a math tool utilized to explore facts and patterns. Further reflection led to discussions of the many intelligences tapped by this activity. I enjoyed the time we made lummi sticks and drums. I used the lummi sticks in the classroom and the students had a great time. We also enjoyed using our spelling words through movement and various voice tones. I know that I will incorporate multiple intelligences theory more and more into the disciplines. It’s like learning through fun! Game playing. The resistance to change, and pressures of everyday teaching, became balanced by student needs. I will remember my emotional content on the day Kaleidoscope was explained. It can be summarized by ‘one more thing to do.’ In contrast, I remember how I felt when I realized the need of Park students to have more mental hooks on which to place information and the importance of Kaleidoscope in developing those hooks. I felt that this was another way to open doors into the minds of children. The feeling was one of hopefulness. Teachers began to form networks of support within and between schools as they learned more about one another, and arts activities presented as classroom models brought richness and meaning into teacher interactions as well. Again, the torn paper illustration of a personal story provided a forum for growth and understanding. 13 Two other art teachers and I talked about our pictures. One asked me to explain my torn paper narrative and I told her it was personal. She said she could tell, and was interested to learn about it. She’s a counselor or therapist as well as an art teacher. Everything was interesting to her and the other art teacher present. She could see things in my picture that I was talking about, more than what I was saying. Sharing with other art teachers and understanding our valid ways of knowing the world has been an important part of Kaleidoscope. It made me aware - this moment - of what we are trying to do - develop language abilities in other areas – we were both communicating - the narrative picture - and teaching and assessing the experience in [pictures and words]. These reactions are as varied as the individuals involved, and as diverse as the experiences across the Michigan City school district. Some reflect personal growth, and some show teacher and student as shared learners. Each had found some magic in the Kaleidoscope experience. READY FOR IMPLEMENTATION The ISTEP-UP funds have thus far promoted a context that has brought together existing resources, provided opportunity for collaboration among community groups, and bridged services for at-risk children. These results are essential if all MCAS students are to become contributing, self-sufficient citizens. With ISTEP-UP as the catalyst, educational opportunities have become more comprehensive in scope, focusing on learning environments that enable learners to become more aware of their diverse strengths, thinking skills, and abilities to approach learning from an arts and multiple intelligences perspective. The eight Kaleidoscope schools are poised and ready to continue in the upcoming year. They are armed with plans, positive energy, increased parental and community involvement, and a district-wide commitment to further in-service and support. Grant proposals are going out to seek funding for this ambitious and worthy program. ISTEPUP funds will not be available for four of the eight schools because they have improved to the point where they are no longer eligible. While it is likely that Kaleidoscope is 14 partially responsible for this apparent improvement, two other factors occurred during the first year of implementation: 1) the ISTEP threshold was changed, and 2) one of the elementary schools was closed. However, it appears that Kaleidoscope has begun to successfully achieve many of the initial program goals. This ironic situation is familiar to those working to improve education. A grant is provided to change a situation, and if the intervention is successful, it disallows candidacy for future funding. This successful program might lose its ability to move forward simply because of its initial success. The schools are then at risk of back-sliding, with student progress undermined. The themes for the second year reflect enormous growth in understanding of integrated curriculum and thematic planning (See Figure 1). Themes are broad, and provide rich opportunities for integrating with integrity for each discipline. The arts are being integrated by teaching in, about and through each arts discipline. Special performances and artists-in-residence are being planned to enhance the themes and arts programs, rather than in place of them. They will provide support and richness. Teachers are communicating across disciplines and grade levels, and parents are becoming involved in positive roles within the school community. Figure 1: 1997-98 Themes SCHOOL Springfield Elementary THEME(S) Personal Best Fest Taste of the Nations Festival of Artists Marsh Elementary Celebration of Feelings Eastport Elementary Workshops for Kids Barker Middle School Progression and Evolution of Cultures and Society Krueger Middle School Around the World in 180 Days Park Elementary Patterns 15 OBSERVATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS: LOCALLY, STATE-WIDE AND BEYOND Jan: As I reflect on this program, I am most amazed at the power of an idea to create excitement, commitment, and energy toward school improvement and enhanced student achievement. I have seen unlikely leaders emerge in this program. In particular, Program Kaleidoscope has enabled our special area teachers of music, physical education, and art to take on leadership roles in their schools. These teachers have generally travelled to several schools and their traveling status has kept them “apart from” the rest of the faculty rather than “a part of” their schools. Although these teachers still service more than one school, the Kaleidoscope Project has helped them bridge this gap, and become integrated into the school learning communities. A couple of examples stand out in my mind. Early in the year, I was asked to meet with one school’s Kaleidoscope team. The physical education teacher serving on the committee spent the entire meeting poking fun at the educational jargon being bandied about, questioning the program’s goals, and testing my commitment to the process (and my endurance/patience as well). However, he did uphold his role as team member and as Fullan (1993) suggests, sometimes changes in behavior precede changes in beliefs. Through this process, he became a strong leader for this program not only in his schools, but on the district curriculum committee for health and physical education as well. Another pleasant surprise, a music teacher who disagreed quite vehemently with our facilitator during the first in-service, later wrote a wonderful article for our local paper in support of the program. Kaleidoscope has given the rest of the faculty the opportunity to collaborate with our special area teachers and to see first-hand the strengths that they have to share. Marsh Elementary School, which has been engaged in significant school improvement over the past four years, utilized the Kaleidoscope Program as the ingredient that helped jell all their other efforts into one. Marsh also relied heavily on parent involvement through parent-child arts interaction nights that were wildly successful and encouraged their families to feel a part of the learning community. 16 This program is truly living up to the early vision of a “kaleidoscopic view” of school improvement and enhanced student achievement. While the goal of improved student achievement in language arts and math through an arts integrated approach served as the foundation lens, each school’s personality, strengths, and student needs are reflected in the ever emerging picture. Carlotta: The desire to help schools implement curricular change is different than knowing exactly how and what to do. This is especially true of knowing the best way to help schools truly interested in integrated curriculum. This program has helped clarify the type of technical assistance that Departments of Education can give to support schools. While the specifics may change for each site because of personnel and local resources (artists, materials, etc.), the processes developed from this program have been defined and a design articulated. These can now be shared with other schools throughout the state or nation. The Michigan City program serves as a model for others who want to develop a true integrated curriculum. The Michigan City administrators and teachers will be able to serve as mentors/resources for other educators in the state. As they become more secure in the process, they will emerge as leaders in this curricular process. Sue: Integrated curriculum design is a hot educational topic across the country and throughout the world. There are many potential opportunities and dangers emerging as programs of varying quality are established. The opportunities lie in the richness of experiences for students and teachers alike, and the potential for learning to become far more meaningful than the traditional model has engendered. Yet, there are few models that build from a comprehensive understanding of integration with integrity that demonstrates understanding of the role of the arts in education and integration. The existing theory I shared was developed out of practice, and was ready to be applied to new situations. It required a special and courageous group to forge the marriage of theory and practice, and be the first to implement the vision. Michigan City Area Schools’ Kaleidoscope Program is the first in-depth, long term effort. The results have been overwhelmingly favorable in terms of student achievement, teacher satisfaction, and change. With this existing model, interested organizations can now replicate the design with their own unique variations. 17 Carlotta: Indiana is not the only place where the word integration is used in thousands of different ways. Unfortunately, and all too often, the word is tossed out as substitute for “arts activities” in the classroom. And, sad but true, there is a dangerous belief that if the classroom teacher “integrates” the arts into the curriculum, money can be saved by eliminating the art, music, and sometimes physical education teachers. The Michigan City program provides a vision for something much different; for something much richer for the lives of students and much more educationally sound. I hope others choose to walk where Michigan City has dared to tread! REFERENCES Fullan, M. (1993). Change forces: Probing the depths of educational reform. New York: The Falmer Press. Snyder, S. (1996). Integrate with Integrity: Music Across the Elementary Curriculum. Norwalk, CT: IDEAS Press. National Association of Elementary School Principals. (1995). National standards for staff development. Alexandria, VA. (1992). Goals 2000: Educate America Act. Washington, DC: United States Congress. POST SCRIPT During the 1998-99 school year, additional schools have begun to implement Kaleidoscope. We have added: an assessment component a strand on parenting and building community support through advocacy, and a Leadership Cadre through which teachers who have been involve from the start can now develop the skills and materials to begin sharing with others. In the PBA assessment recently completed by the state, every school in Michigan City got accreditation for the next five years. Kaleidoscope certainly contributed to this turnaround. 18 19 ABSTRACT Michigan City Area Schools received a school improvement grant and used the challenge to develop an arts-integrated program in eight struggling schools. The goals of the Kaleidoscope Program were to improve language and math scores; foster collaborations between faculty members and the community; build multicultural understanding; and utilize a multiple intelligences perspective to observe, teach and assess students. Three individuals representing the perspectives of district, state and outside consultant shared leadership to facilitate the change process. The program evolved over time, and led to changes in attitudes, teaching, and goals set for students; and ultimately toward significantly raised scores for four of the eight schools. In addition to the program’s quantitative success, less measurable outcomes were evident in teachers, students, and school communities. Documentation of this program provides additional support for the growing number of successes gained through arts-integrated curriculum planning. KEY WORDS integrated arts low achievement curriculum development collaboration change 20 AUTHORS BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES Dr. N. Carlotta Parr is Indiana State Consultant for Fine Arts. Dr. Jan Radford is the administrative assistant for curriculum & instruction for the Michigan City Area Schools. Her responsibilities include facilitating grant programs, program development, student services, and the related professional development. Dr. Susan Snyder is President of Inventive Designs for Education & the ArtS (IDEAS), a consulting and publishing company dedicated to facilitating excellence in education. She has taught at all levels from early childhood through post-graduate, and is currently a Scholar-in-Residence in the BEST Program at the Connecticut State Department of Education. 21 CAPTIONS FOR PHOTOGRAPHS #1 - Weaving ribbons and thoughts about how weaving can be represented through each intelligence.. #2 - Discussing big questions for a new theme - What is really important for the children to know at the end of this unit? #3 - Storyboarding helps focus on past, present and future, and provides a record of how far each school group has come. #4 - The torn paper quilt squares provided a visual representation of individual stories, the sum of which created a model of our learning community. 22