Surgery Student Communications Primer

advertisement

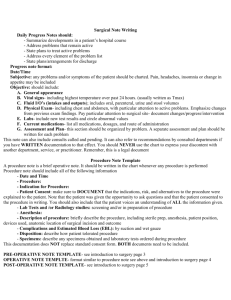

Surgery Student Communications Primer Objectives: 1. Medical students will understand the importance of developing clear and concise communications skills. 2. Students will understand the core elements of communications with patients. 3. Students will understand the core elements of oral and written communications with colleagues, and the importance of tailoring communications to the listener and environment. 4. Students will work through communications exercises. Surgery Communications Primer Page 1 of 16 I. Importance of Communicating Effectively For Patient Care Professionalism Clear communications are integral to patient autonomy and informed consent.1,2 Competencies Communication skills are considered one of the ACGME competencies and are integral to other competencies such as systems-based practice and patient care.3 Patient Safety Miscommunication is a leading cause of preventable medical errors.4 1 Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. ABIM Foundation, ACP– ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243246. 2 Ref UNC Professionalism docs, again show place of communications. 3 http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compCPRL.asp 4 Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000. Surgery Communications Primer Page 2 of 16 For Caregiver and Institutional Protection Medicolegal protection Clear communications are vital to the process of informed consent and its documentation. As well, poor communications are believed to account for about 70% of surgical errors5 that lead to medical malpractice claims. Unstructured verbal communications are most often the source of these errors, so systems to improve communications are advocated to improve patient safety.6 Billing All billing services depend upon coding from written documentation in medical records. Institutions or individuals coding and billing for more than is appropriately documented in the medical record may be charged with fraud irrespective of the level of care actually provided. “If it is not in the chart you did not do it.” Compliance Hospital contracts depend on record keeping and compliance with mandated standards. 5 The Joint Commission. Sentinel events statistics—June 30, 2006. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvent/Statistics/. 6 Greenberg C, Regenbogen S, Studdert D, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533-40. Surgery Communications Primer Page 3 of 16 II. Core Elements of Communications with Patients7 According to the Bayer Institute for Health Care Communication, a clinician’s role in communicating effectively with patients can be broken down into a process that includes the following communication tasks: engagement, empathy, education and enlistment. Engagement Engagement depends upon a connection between the clinician and patient. This must continue throughout the encounter and will set the stage for a partnership. introduce yourself do not grill the patient try not to interrupt the patient’s story show interest in the patient as a person, o eliciting the patient’s agenda and expectations o negotiate and prioritize the agenda for the visit o use the patient’s language rather than medical jargon Remember the expression, "You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression." Be cognizant that both your actions and your words express your interest in the patient as well as the medical problems they bring to the table. The outcomes of successful engagement are rewarding. For example, the quantity and quality of the diagnostic information available will improve. The groundwork for a successful relationship will have been laid. Additionally, the patient will have a sense of partnership with the clinician, which will facilitate adherence to a treatment regimen. Empathy Empathy is sincere—and successful—when a patient acknowledges that he or she has been seen, heard, and accepted as a person. This seems like a simple concept, yet the effective use of empathy presents common dilemmas for clinicians. Once again, clinicians who fall back on "comfortable" medical language create a barrier to empathy. Additionally, clinicians often confuse sympathy with empathy. What’s more, although research proves it to be untrue, some clinicians may feel that empathizing with a patient will require more time than they have to give. New patients should be seen fully clothed Proper introductions should be made Sit on level with the patient’s line of sight Avoid physical barriers or distractions 7 Mock KD. http://www.physiciansnews.com/law/201.html Surgery Communications Primer Page 4 of 16 To effectively hear a patient, invite him or her to share thoughts and feelings and then affirm them by using the patient’s own words. Hearing also means allowing the patient to correct your understanding of what was said to ensure agreement. Acceptance requires acknowledging the patient’s thoughts and feeling while reserving judgment. It also allows for self-disclosure, when appropriate. Don’t tell your life story, but do share anecdotes that will facilitate the clinician-patient bond. Keep in mind that by encouraging "windows of opportunity" through the use of open-ended questions, you will be better prepared to address the psychological and social, as well as medical, needs of the patient. Education Education has taken place when the cognitive, behavioral, and effective needs of the patient are addressed. Research shows that clinicians overestimate the time spent in the education of their patients by nine times! In reality, approximately one minute is actually spent on this crucially important task. Poor education of patients is clearly a product of poor communication skills on the part of the clinician. To effectively communicate, first assess what the patient already knows and then ask questions to determine what he or she might be wondering. Not all patients will be forthcoming with questions, so be prepared to probe empathetically to discover their most basic concerns and fears. Educating a patient involves providing increased knowledge and understanding while at the same time, decreasing uncertainty and anxiety. Assess the patient’s current knowledge Ask about their understanding of the disease process Ask "what do you think is going on?" All patients have the same questions, whether or not they ask them… Surgery Communications Primer What has happened to me? Why has this happened to me? What will be done to me? Why will they do this rather than that? Will it hurt? When will you have the answers (test results)? When will I have the results? Page 5 of 16 Remember that education has not taken place until the patient has learned something. Be sure that all questions have been answered. Then ask how the patient understands, not if the patient understands. Also, consider that health terms may have both a clinical and lay meaning. Be clear in describing or defining terms to avoid confusion, making sure that you and the patient are on the same page. Successful education brings great rewards. The relationship between the patient and the clinician is enhanced and the patient becomes part of the process. The patient will know and understand what is happening, what to expect, and therefore, will be less anxious. You will not bear total and sole responsibility for the implementation of the proposed regimen and both of you will be partners in a successful treatment plan, creating a high level of mutual satisfaction. Enlistment Enlistment is an invitation by the clinician to the patient to collaborate in decision-making regarding the problem and the treatment plan. It is a challenge to the health care provider to create a plan of treatment that the patient will accept and to which he or she will adhere. As all practitioners know, patient non-adherence is a tremendous problem. Research shows that several things affect adherence: patient’s perception of the illness, efficacy of treatment, and duration of treatment. What is clearly presented is that the relationship between the clinician and the patient is a critical factor in patient adherence. Before they even enter the clinician’s office, most patients have made their own diagnosis—a diagnosis that more often than not, they are looking to confirm. Enlistment requires that a clinician and patient come to an agreement about the problem and prescribed treatment. To ensure collaboration, provide a "possible explanation" and ask how it fits with what the patient has been thinking. Differences in diagnoses need to be reconciled or the patient is likely to follow his or her own. Lay out the variables for the patient in a simple format Include indications risks and benefits of options Ask for feedback to ensure true collaboration Be prepared to tailor the course of treatment to best suit the patient’s needs and overall health Close by summarizing the agreed-upon plan and discussing next steps Surgery Communications Primer Page 6 of 16 Creating a Win-Win Situation Although patient communication is the most common and easiest-to-improve medical procedure, its significance is often overlooked. Effective communication is the key to adopting a patient-centric approach to providing medical care, and to the reduction of adversarial clinician-patient relationships. By incorporating effective communication techniques into daily patient interactions, clinicians can decrease their malpractice risk. More importantly, clinicians can positively and effectively impact patient health outcomes without increasing the length of visit—a win-win situation for both parties, and indeed the goal of health care. III. Core Elements of Communications with Colleagues A. Effective Oral Communications As a member of a clinical care team, your patients depend upon your ability to communicate effectively and honestly. Whether you are presenting an H&P or a “SOAP” assessment, there is value in committing in a common structure. Colleagues who share a structured pattern of communicating do so with more efficiency and fewer errors. A special language reduces distractions. The short order chef knows the meaning of your waitress’ call of “eggs up.” Your short tempered chief resident will know the meaning of “T-max.” One way to commit to a common structure is to use “signposts” in your narrative. These short phrases, when spoken aloud, reorient and refocus the listener. In the real world, a speaker may say, “so in conclusion…” In anatomy lecture the professor may say “pay careful attention to this next point…” In clinical medicine we orient the listener with statements like “on physical exam…” or “so in summary…” S: In delivering a medical history in an H&P, or the subjective information in a SOAP presentation, fewer words are generally better, but while maintaining sentence structure. We do not hear in bullet points. One good way to limit wordiness is to write things down beforehand. Medical students will learn the value of pre-rounding. This gives the student a chance to process the information and to draw the data into the correct structure for presentation on rounds. Another way to improve is to practice and to pay attention to the feedback of the members of the team. If you find people asking for the vital signs (see “O”), they are asking you to move along. O: In delivering objective data, including vital signs and physical exam findings, editorializing is distracting and assessments are premature. Fabrication is a sin. Your team will be listening for things in a certain format. If you said BP is “120 over 60”, they are hearing you, if you say “diastolic pressure was a little low at 80 and systolic pressure was 120” you have made everyone wonder why you think 80 is low and if you drive on the wrong side of the road. While they were imagining you driving they might not have Surgery Communications Primer Page 7 of 16 actually processed the information you were sending. So follow the conventions and do not editorialize here. A/P: This is the part of the presentation where you can shine. You have collected and presented the data, and now it is your chance to put it together like a physician. In integrating the subjective and objective data, the assessment and plan still benefits from a structured analysis and delivery. Most of us think through a systematic checklist on every patient every day, so as not to miss a key issue, and then present the summary of this process in a way appropriate to the level of care. For example, a critical care presentation will always consider each of the major systems explicitly, whereas a postoperative appendectomy presentation will leave unspoken some of the systems considered. Know the Listener and Environment Speaking to Other Caregivers Most medical communications occur when two physicians are passing like trains in the night. The receptivity of the listener is affected by his or her ongoing activities and agendas, including beepers going off and patients waiting. So, it is imperative that the person initiating the communications secures the attention of the listener and delivers the information efficiently. Having your thoughts organized is part of the challenge. Sign out lists with written annotations will ensure the transfer of information is complete and will serve to remind the listener of the details of the conversation. Engaging in two-way conversation and fielding questions from the receiving party will also avoid misunderstanding. Pilots and spouses know that a simple statement of acknowledgement, whether it is a “check” or a “yes I’ll pick up Jimmy,” is the only way to transfer important responsibility without doubt. If you say “this patient needs a blood draw at 8PM,” your colleague should say something like “OK, is it a stat draw?” or even “check,” but should not say something like “what time is the game on tonight?” Sometimes you will be called upon to present a patient you have evaluated to a supervising physician. Maybe you are the first one to see a patient with abdominal pain in the emergency room. You will collect the history from the patient, perform your physical exam, perhaps review studies and then develop an assessment and plan. Then you will call your senior colleague to report on the consultation. Consider these two presentations of the same patient: 1. “I have a consult to present. Ms. Smith is a 22 year-old student who presented to the student health center with abdominal pain. She was seen by the clinic physicians and they called us for a surgical consult. Two days ago the pain Surgery Communications Primer Page 8 of 16 began after she ate Chinese food. She was concerned that she had food poisoning, but none of her other friends got sick. She felt a little warm but didn’t take her temperature. Her abdomen was hurting but she went to class. Later she was feeling like she maybe was doing a little better so she went to a party but couldn’t eat anything. She works as a chemistry graduate student and hasn’t been on any foreign travel recently. Her mother has a history of breast cancer and her father died of coronary disease when she was a little girl. She never had surgery. She smokes a rare cigarette, and drinks socially. Her review of systems is negative of weakness, numbness, shortness of breath, melena, hematochezia, bleeding, clotting, weight loss, rashes, arthralgias, chest pain, or other symptoms. She was seen in the clinic and had bloods drawn including a CBC, lytes and urine. All of there were normal except the WBC was slightly elevated and the urinalysis had a few red blood cells but she is menstruating. Oh, incidentally she is not sexually active and has never had any STDs. Anyway, I did a physical and she was tender in the lower abdomen on the right side, with a little bit of guarding and rebound but I am not sure if it was peritonitis. A CT scan was ordered and it showed there was non-filling of the appendix with surrounding inflammation. So I was wondering what you wanted me to do.” OR 2. “I have a consult to present. Ms Smith is a 22 year-old student who presented to the student health center 2 hours ago with abdominal pain. I think she has acute appendicitis. She was well until 2 days ago when she developed periumbilical abdominal pain and anorexia. Over the last 2 days the pain has migrated to the RLQ. She has no vomiting or diarrhea. She has not had recent infectious exposures or foreign travel. She has never had abdominal surgery. She is menstruating now. Remaining history is negative. Physical exam is consistent with focal peritonitis in the RLQ at McBurney’s point. Pelvic exam was negative. WBC was 12K. U/A had a few RBCs. CT scan is consistent with early appendicitis. I’ve called the OR and we can get her there for lap appy in 1 hour. I’ll give her a dose of prophylactic antibiotics and call you when she is in the holding area. Is there anything else I need to do?” The second presentation is much better. Sure, it is better organized and flows more easily. It sounds like a story because it is chronological and filtered. Most importantly, the presenter has taken a stand in saying “acute appendicitis” up front, so the listener can judge each of the following statements as supporting or refuting the proposed diagnosis. This is much preferred to the ‘mystery-novel’ approach where the presenter provides Surgery Communications Primer Page 9 of 16 every bit of information and hopes the listener will come to the same conclusion. Notice the first presenter did not have an assessment and plan as part of the presentation but the second presenter did. As one matures in clinical medicine, one development scale describes the transitions from data reporter (R) to data interpreter (I), and later to a manager (M) and educator (E).8 The first presenter is a reporter, whereas the second is at least an interpreter on the RIME scale. Given the excellent presentation and decision making demonstrated, this learner may get to prove whether or not he or she is a manager in the operation. There are other standards of healthcare communications that must be understood and followed. Maintaining patient privacy is a responsibility our profession demands. Be discreet in sharing private health information with other team members in the public areas of the hospital. Never share patient information with non-caregivers. Never look at healthcare records of patients with whom you are not involved. Presenting to Evaluators As a learner who is being evaluated, it is important you comprehend the expectations of your evaluators. A. Complete H/P – In certain new patient evaluations, such as when you are on Internal Medicine or Family Practice, you will be expected to cast a wide net during history taking and examination to create a complete problem list for the patient. When presenting overnight admission to the Chief of Medicine during morning report, this is the level of preparedness to bring to the table. 8 Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74:1203–7. Surgery Communications Primer Page 10 of 16 B. Focused H/P – On the Surgery clerkship, most listeners are anticipating a problem-focused presentation, even for a new patient. In collecting the data, it is reasonable to begin formulating a differential diagnosis as you hear the chief complaint and the presenting symptoms. If a patient describes right upper quadrant pain and nausea, you are prompted to ask questions about jaundice, light stools, dark urine… because biliary stone disease has risen to the top of the list of possible diagnoses. You should also ask questions that pertain to secondary possible diagnoses, such as EtOH use, travel, etc. As you roll through the past medical and surgical history, and medications, again it is reasonable to focus on areas connected to the diagnosis and treatment of this patient with RUQ pain…prior biliary tract disease or surgery, history of urinary stones, colon disease, etc. However, remember that all surgeons must also collect information about the cardiopulmonary status of the patient who may soon be offered general anesthesia and operation. The same degree of focus is appropriate for eliciting the social history, family history, review of systems, and physical exam findings. In communicating to your evaluators, it is best to begin with a clearly stated diagnosis up front, such as “this is a 40 year-old female with acute cholecystitis,” stated at the beginning, so your listeners will see you as definitive, and will hear everything you say as supporting your leading diagnosis, refuting a secondary diagnosis, or describing an important issue in the patient’s history that will impact care. The justification for the focused H/P is time and efficiency. Some surgical diagnoses, such as a ruptured aneurysm, will not wait for a full review of systems. Likewise, follow-up interactions in clinic or on the hospital wards do not require retracing previously covered ground. If a clinic has a defined time allocated and a certain number of patients scheduled, set your pace for each patient encounter with the team goals in mind. Ask your attending or resident how long you have before you enter a room. C. AM Rounds – In your Surgery clerkship, morning rounds are considered work rounds. The team goal is to see all the patients before the start of scheduled OR cases or clinics. As a member of the team, if your patient presentations are efficient and trustworthy, and you find Surgery Communications Primer Page 11 of 16 ways to contribute to this effort, you will earn the trust and appreciation of your teammates. If you spend the entire rotation struggling to understand, resisting the accepted format for presenting, or putting your personal needs ahead of collective needs, you will feel as an outsider. So pre-round on your patients, have the data organized, and deliver in a clear SOAP note. Help out by offering to dress a wound or look up a lab value. Save your questions for times when the clock is not ticking. D. PM Rounds - In your Surgery clerkship, these are considered follow-up work and teaching rounds. Most other specialties meet once per day, but surgeons traditionally meet twice to discuss interval issues of care (follow-up of tests and imaging) and for teaching purposes. Take responsibility for your patients by tracking down the pertinent test results and seeing your patient during the work day. Be prepared to discuss the issues of the day on PM rounds in an extremely concise format. These rounds are intended to serve the dual purpose of securing patients for the night and also to provide education time. Ask your questions and hold those faculty and residents accountable to your needs! B. Effective Written Communications The written medical record has always been seen by providers as a place for concise documentation of the flow of patient care and medical decisions. Over recent years, this record has been increasingly called upon to serve as a chronicle of billable activity and compliance, and the template for medico-legal scrutiny. Unfortunately, the clarity of patient care documentation is sometimes affected adversely by efforts to use the medical record for parallel purposes. Implementation of electronic medical records and order writing systems are driven by the desire to streamline patient care and to reduce error. These systems have impacted the ability of medical students to easily participate in medical record writing. Despite these challenges, medical students must learn the basics of medical documentation and order writing and have a forum for practice. A. History and Physical Exam – The major sections of a written surgical H/P follow the standard form taught in your Physical Diagnosis class, and should be included explicitly. The elements in the history must include the chief complaint (CC), history of present illness (HPI), medical history, surgical history, medications, allergies, social history, family history and review of systems. The physical examination includes General, HEENT, Neck, Lungs, Heart, Abdomen, Surgery Communications Primer Page 12 of 16 Extremities and Neuro. The pertinent positives and negatives should be documented under each section. Abbreviations and jargon are sometimes helpful, but are distracting if overused. Many clinicians would prefer use of a qualifier “normal” over rewriting the specific comment “no clubbing, cyanosis or edema” every day over a 2-week admission for bowel obstruction. When you think about it, is clubbing really associated in any way with the patient’s active medical issue? Perhaps “normal” carries more information in fewer words. On the other hand, excessive wordiness in a written H/P is even more distracting than excessive abbreviation. The HPI should read as a concise, chronological narrative, whereas the rest of the document should use bullet points and lists liberally in reflecting the medical history, medications, surgical procedures, and assessments and plans. B. Progress Notes – These follow “S-O-A-P” format strictly. Like H/Ps, these progress notes need to be well organized on the page to allow someone scanning through the medical record to follow trends. Always identify the note clearly as a “Medical Student Progress Note,” including the date and time. S: O: A/P: Briefly describe the interval issues subjectively since the last note. Tmax, T current, BP, HR, RR 24 hr ins/outs, last shift I/Os Include drain output Physical exam findings Gen Lungs Cor Abd Ext Neuro Organized by systems for complex cases C. Procedure Notes – These are immediately placed in the written record. Often, a more complete note will follow after a transcription process. Date and Time Preoperative Diagnosis Postoperative Diagnosis Procedure Surgeons Estimated blood loss (EBL) Blood Products Fluids Complications Drains Surgery Communications Primer Page 13 of 16 D. Post-op Notes – The postoperative check/postoperative note is a visit made by oncall providers to operated patients on the evening of the procedure. These assessments and written documents follow the usual progress note format, but pay particular attention to fluid dynamics and postoperative pain management. E. Orders – A set of new orders is usually required whenever a patient changes from one level of care to another. This can mean moving from the OR to the recovery room, or from the hospital floor to the ICU. Electronic order systems have diminished some of this requirement, as orders can be reviewed/validated and not re-written in some settings, but students still need to have a system for writing orders so that important items are not forgotten or overlooked. Most physicians learned to write inpatient orders using a pneumonic such as “ADC VANDIML.” A= Admit to unit D=Diagnosis: ____________ C=Condition (Stable, fair, critical, etc.) V=Vital signs frequency A=Allergies: list them A=Activity (out of bed?, bedrest?, etc.) N=Nursing (I/Os, call houseofficer parameters, tubes and lines management, prophylactic measures, etc.) D=Diet (regular, full liquids, Low fat, etc.) I=IV order M=Meds (chronic medications, pain medications, prn medications, prophylactic medications, etc.) L=Labs Prescription writing is another ability that is acquired during medical school and early residency. The typical prescription includes: Patient Name__________________________________ Date________ Medication name (strength or concentration) Number pills or volume to dispense Instructions for use (to be put on bottle) # of refills______ Name / Signature______________________DEA number_____________ Develop a system and practice. There are no substitutions for this prescription. Surgery Communications Primer Page 14 of 16 IV. Communications Exercise (self reflection exercises) Non-English speaking, unsophisticated, adult pt, mother in room, sensitive topic – cervical cancer, get permission for bx. How do cultural and language differences challenge effective communications? What methods for cultural sensitivity can you apply in these situations? What pressures negatively affect your ability to communicate with your patients? What can you do to work through them? What are some specific techniques you can use to ensure that patients have understood what you have shared with them? Delivery of bad news – cancer In delivering a diagnosis of cancer, is it best to be blunt or gentle? How do you balance the need to deliver information clearly with sensitivity to the patient’s emotions? After processing the information delivered, what questions will the usual patient have about having cancer? Can you empathize with this patient and list the likely questions you would want to have answered? As the physician, are you prepared to answer them? Oral communications with specialist If you feel this patient’s care is outside of your expertise, and you want to make a referral to a GYN oncologist, is it important to call? What value might there be in verbally communicating to a specialist? Written referral to a specialist If you have made the referral verbally, is it important to write a referral note/summary? Could you write a brief referral note to a specialist clearly defining the patient’s needs and social issues? How much should you include? Discovery that biopsy was an Error – Report to Patient A week later a lab worker calls to say the biopsy reported was that of another patient. The biopsy of your patient was misplaced. What would you tell her? Imagine her response. How would you assure her understanding of the change in your advice, accommodate her reaction, and guarantee appropriate care is delivered from here? How would you amend the patient’s medical record and document the discussion? Surgery Communications Primer Page 15 of 16 When mistakes occur, how do effective communications and a personal relationship with your patients decrease the chance of litigation? M/M oral communication If your patient suffered a systems error, is it your responsibility to investigate the system that failed her? How would you gather information about this case? Would you discuss this case at your departmental Morbidity and Mortality conference? How would you present the case? What are the benefits of presenting errors in M/M conference? Legal deposition A year later, you are contacted by the patient’s attorney about the emotional suffering she endured as a result of this error. You are asked to sit in a deposition to discuss the case. As a treating physician, how does a carefully written medical help you in this setting? Surgery Communications Primer Page 16 of 16