Stacy Kingsland

advertisement

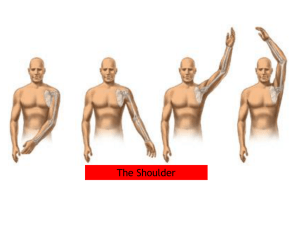

Stacy M. Kingsland Musculoskeletal Rotation 4/28/2006 The Shoulder: History, Exam and Diagnosis The patient with shoulder pain; a frightening encounter to the Internal Medicine Resident or at least it was to me until this month. Why is the shoulder so scary and mysterious? Perhaps it is because of the complexity of the joint and our inexperience with the exam. This month with the guidance and expertise of Dr. Gardner and Dr. Nakamoto I have been fortunate enough to become more familiar with the exam, the findings and how to proceed with a workup. Here is the way I have learned to break it down so it both easy for me to remember and understand. To begin with it helps to have a basic understanding of the anatomy of the shoulder. The shoulder is made up of the humerus, glenoid, scapula, acromion and clavicle plus the surrounding tissues. (1,2). The joints of the shoulder include the glenohumeral joint, acromioclavicular (AC) joint, sernoclavicular joint and scapulothoracic articulations. The tendons of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis make up the rotator cuff which stabilized the glenohumeral joint. The muscles themselves provide movement about the joint. Now that there is a very basic understanding of the shoulder anatomy, to begin evaluating a patient with shoulder pain start with the history. In evaluating patients with shoulder injuries you want to know about there dominant hand, sports activity, limitations from the pain and occupation as these things will guide the aggressiveness of treatment and help you understand the patient’s functional needs (1,2). Also, do not forget to ask about other medical problems such as diabetes which can predispose you to adhesive capsulitis or other disease that can cause referred pain to the shoulder such as cervical neck injuries/arthritis, coronary artery disease, pneumonia, peptic ulcer disease, malignancies or neurovascular diseases (2). Assuming the patient’s pain truly is a result of shoulder pathology asking specific questions about possible trauma and the location, duration, quality and type of pain is helpful. The following in table 1 are examples of complaints and associated possible diagnoses (2): Table 1: History Scapular winging, trauma, recent viral illness Seizure and inability to passively or actively rotate affected arm externally Supraspinatus/infraspinatus wasting Pain radiating below elbow; decreased cervical range of motion Shoulder pain in throwing athletes; anterior glenohumeral joint pain and impingement Pain or "clunking" sound with overhead motion Nighttime shoulder pain Generalized ligamentous laxity Possible diagnosis Serratus anterior or trapezius dysfunction Posterior shoulder dislocation Rotator cuff tear; suprascapular nerve entrapment Cervical disc disease Glenohumeral joint instability Labral disorder Impingement Multidirectional instability Chart taken from Woodward, Best (2) Once you have the initial history the next step is the exam. Having a generalized understanding of the anatomy is key to being able to perform and interpret the exam. The exam begins with inspection, looking for asymmetry, deformity, bruising, masses or other clues to the diagnosis. Next is palpation of the C-spine, AC joint, lateral acromion and biceps tendon. Pain over the AC joint could represent arthritis, pain over the lateral acromion could represent a bursitis and pain over the biceps tendon could represent a biceps tendonitis. After palpation comes ROM and muscle strength testing. This is where knowledge of the rotator cuff anatomy makes the exam easier to remember and correlate findings. The first rotator cuff muscle/tendon tested is the supraspinatus. Range of motion is tested with forward flexion 0-180 degrees. Patients may have more pain with eccentric contraction or on bringing the arm back from 180-0 degrees with a significant supraspinatus injury. To test supraspinatous strength have the patient perform the “empty can sign.” You have the patient abduct the shoulders to 90 degrees in forward flexion with the thumbs pointing downward and then the patient attempts to elevate the arms against examiner resistance (1,2). With this maneuver it is important to make sure the patient’s thumbs are pointed downward to really isolate the supraspinatous muscle. The next muscles/tendons evaluated are the infraspinatus and teres minor which work to externally rotate the shoulder. Range of motion is tested by having the patient place their elbows at their sides and externally rotate their arms between 0-80 degrees. To test strength this maneuver is repeated against examiner resistance. The last muscle/tendon tested is the subscapularis which is responsible for internal rotation. Range of motion is first tested by examining how far the patient can internally rotate and reach up their back with their thumb. Normal range of motion is ability to reach to about T7-T4. Next strength is tested via the “lift off test.” The patient rests the dorsum of the hand on the back in the lumbar area and then moves it out from the lumbar area and presses against resistance (1,2). With all maneuvers it is important to determine true weakness versus inability to perform the tests secondary to pain. True weakness is suggestive of a muscle tear where as pain alone may represent only a tendonitis. Next are the “provocative maneuvers.” These tests can help you distinguish impingement versus AC joint compression versus biceps tendonitis. There are multiple “provocative maneuvers” (see table 2) (2); however, the ones I am going to discuss are the techniques I became familiar with under the direction of Dr. Nakamoto. The tests for impingement I a going to discuss are the Hawkins’ test and Neers’ test. Hawkins’ test is performed by elevating the patient's arm forward to 90 degrees while forcibly internally rotating the shoulder. Pain with this maneuver suggests subacromial impingement or rotator cuff tendonitis (2). Neers’ test is performed by placing the arm in forced flexion with the arm fully pronated. The scapula should be stabilized during the maneuver to prevent scapulothoracic motion. Pain with this maneuver is a sign of subacromial impingement (2). To test for AC joint compression have the patient raise the affected arm to 90 degrees and then place the arm in active adduction providing force across the acromion into the distal end of the clavicle. Pain in the area of the AC joint suggests a disorder in this region (1,2). Lastly, to test for pain coming from the biceps tendon, do the Yergason’s test. To perform this test have the patient flex the elbow to 90 degrees with the forearm pronated (1,2). Pain with this maneuver suggests biceps tendonitis or instability. TABLE 2 Tests Used in Shoulder Evaluation and Significance of Positive Findings Test Provocative Maneuver Diagnosis suggested by positive result Apley scratch test Patient touches superior and inferior aspects of opposite scapula Loss of range of motion: rotator cuff problem Neer's sign Arm in full flexion Subacromial impingement Hawkins' test Forward flexion of the shoulder to 90 degrees and internal rotation Supraspinatus tendon impingement Drop-arm test Arm lowered slowly to waist Rotator cuff tear Cross-arm test Forward elevation to 90 degrees and active adduction Acromioclavicular joint arthritis Spurling's test Spine extended with head rotated to affected shoulder while axially loaded Cervical nerve root disorder Apprehension test Anterior pressure on the humerus with external rotation Anterior glenohumeral instability Relocation test Posterior force on humerus while externally rotating the arm Anterior glenohumeral instability Sulcus sign Pulling downward on elbow or wrist Inferior glenohumeral instability Yergason test Elbow flexed to 90 degrees with forearm pronated Biceps tendon instability or tendonitis Speed's maneuver Elbow flexed 20 to 30 degrees and forearm supinated Biceps tendon instability or tendonitis "Clunk" sign Rotation of loaded shoulder from extension to forward flexion Labral disorder Table 2 taken from Woodward, Best (2) The last part of the shoulder exam is to test for glenohumeral instability. This can be done using the anterior apprehension test and the relocation test (1,2) The anterior apprehension test is performed by placing the patient supine and the shoulder in a neutral position at 90 degrees of abduction. Next, apply slight anterior pressure to the humerus and externally rotates the arm. Pain or apprehension about the feeling of impending dislocation indicates anterior glenohumeral instability (1,2). If the apprehension test is positive one continues on with the relocation test. To perform this test keep the patient supine, and apply posterior force on the proximal humerus while externally rotating the patient's arm. A decrease in pain or apprehension suggests anterior glenohumeral instability (1,2). When looking for instability one is also looking for asymmetry in laxity between each of the shoulder joints. If the above exam is negative do not forget to look for other things that could be causing the patient’s shoulder pain, again paying close attention to the possibility of Cspine pain or other referred pain. Putting together the history and physical exam should guide you toward a diagnosis. Fractures for the most part will have specific tenderness, may be associated with swelling, bruising and x-ray findings. Shoulder dislocations will reveal shoulder asymmetry and weakness. AC joint arthritis will reveal AC tenderness, pain with provocative maneuvers and x-ray findings. Glenohumeral joint arthritis will reveal decreased range of motion, pain and x-ray findings. Impingement will show decreased range of motion and positive impingement signs with “provocative maneuvers.” Rotator cuff tendonitis will reveal decreased range of motion and pain that may limit strength on testing range of motion and strength of the rotator cuff tendons. Definite weakness in the rotator cuff exam is concerning for a tear. Adhesive capsulitis shows decreased range of motion in all direction with both passive and active range of motion of the shoulder joint. Shoulder instability will reveal a positive apprehension and relocation test. The above guidelines have given me the basics to understand the shoulder pathology and how to at least start an evaluation, what parts of the shoulder to be suspicious of as causing the patient’s difficulties and what to do next. At least now I may not be so scared of the shoulder exam References: 1.Baker CL, Merkley MS. Clinical Evaluation of the Athlete’s Shoulder. Journal of Athletic Training. 2000 July:35 (3):256-260. 2. Woodward TW, Best TM. The painful shoulder: part I. Clinical evaluation. American Family Physician. 2000 May 15;61(10):3079-88. Special thank you to Dr. Greg Gardner and Dr. Greg Nakamoto for their instruction in how to evaluate shoulder pathology!!