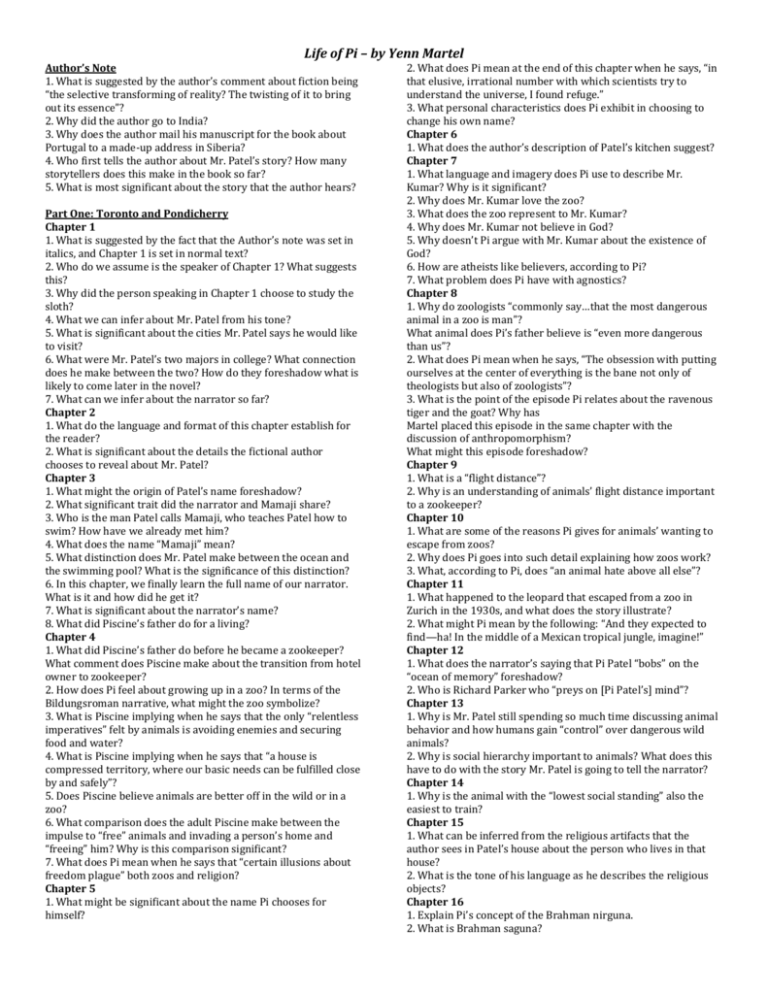

Guided Reading Questions

advertisement