TMZCaelyx

advertisement

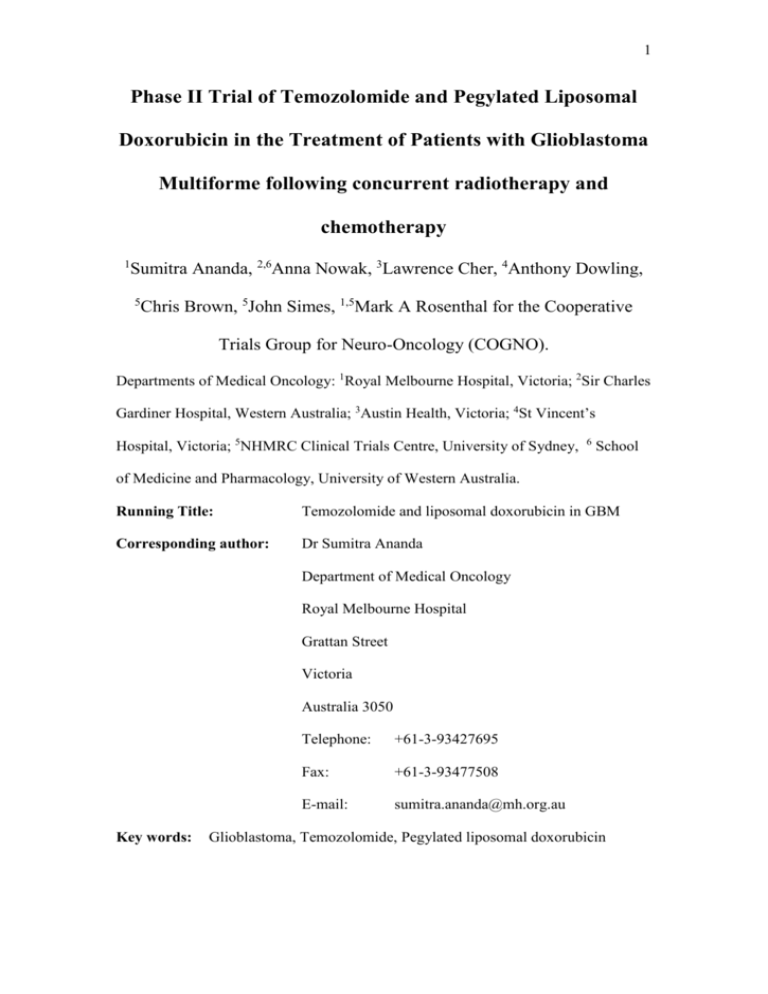

1 Phase II Trial of Temozolomide and Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin in the Treatment of Patients with Glioblastoma Multiforme following concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy 1 Sumitra Ananda, 2,6Anna Nowak, 3Lawrence Cher, 4Anthony Dowling, 5 Chris Brown, 5John Simes, 1,5Mark A Rosenthal for the Cooperative Trials Group for Neuro-Oncology (COGNO). Departments of Medical Oncology: 1Royal Melbourne Hospital, Victoria; 2Sir Charles Gardiner Hospital, Western Australia; 3Austin Health, Victoria; 4St Vincent’s Hospital, Victoria; 5NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney, 6 School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia. Running Title: Temozolomide and liposomal doxorubicin in GBM Corresponding author: Dr Sumitra Ananda Department of Medical Oncology Royal Melbourne Hospital Grattan Street Victoria Australia 3050 Key words: Telephone: +61-3-93427695 Fax: +61-3-93477508 E-mail: sumitra.ananda@mh.org.au Glioblastoma, Temozolomide, Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin 2 Funding- This investigator-initiated trial was supported by an unrestricted grant from Schering-Plough and by Cancer Australia. The study was conducted and analysed independently of S-P and CA 3 Abstract Introduction: Concurrent and post-radiotherapy temozolomide (T) significantly improves survival in patient (pts) with newly diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). The combination of T and PLD can be used safely at full doses and Phase 2 data supports efficacy of this combination in recurrent GBM. We aimed to assess the activity of this combination as part of treatment for newly diagnosed GBM. Methods: In this study, the combination of T (200mg/m2 orally, days 1-5) and PLD (40mg/m2 iv day 1) was given every 4 weeks for a maximum of 6 cycles following combination chemo-radiotherapy as post-operative treatment for GBM. The primary endpoint was 6 month progression free survival (6PFS) measured from treatment commencement using a Simon two stage approach. Results: 40 patients were enrolled: median age was 53 years and 73% were males. 6PFS was 58% (95%CI 4172%). The median time to progression was 6.2 months (range 95%CI 5.6-8.0 months) and for overall survival (OS) was 13.4 months (95%CI 12.7-15.8 months) respectively. Of 34 patients with measurable disease, one had a complete response (3%), 28 had stable disease (70%), 5 (12%) progressive disease and the rest were not evaluable. Treatment was well tolerated: hematological toxicity included grade 3 neutropenia in 3 patients (8%) but no Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia was observed. Grade 3 nonhematologic toxicity included nausea and vomiting (8%) and palmar-plantar toxicity (5%). Conclusions: Combination T and PLD is well tolerated but does not appear to add significant clinical benefit regarding 6PFS and OS in the treatment of newly diagnosed GBM. Word count: 249 4 Introduction The annual incidence of malignant gliomas is approximately five cases per 100,000 people, with more than 14,000 new cases diagnosed annually and 13,000 deaths in the United States.1, 2, 3 The current standard of care for suitable patients with newly diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) is maximum surgical resection followed by concurrent temozolomide and irradiation followed by six months of temozolomide. The two and five year survival rates from initial diagnosis with this regimen are 26.5% and 9.8% respectively; more effective treatments are needed.4, 5 Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) is a formulation of doxorubicin in which the drug is encapsulated in liposomes (Stealth liposomes) that can avoid uptake by the reticuloendothelial system.6 Liposomal encapsulation may ameliorate the toxicity of doxorubicin by reducing both the non-specific drug delivery to normal tissues and the high peak plasma levels of free drug. Once concentrated in tumours, the liposomes of PLD may deliver high levels of doxorubicin locally, reducing toxicity without compromising efficacy, and improving the therapeutic index.7 Liposomal doxorubicin has been tested in preclinical glioma models and appears to have significantly improved penetration compared with doxorubicin itself.8-10 However, there is only limited data regarding its use in the treatment of recurrent high grade glioma. One Phase I/II study demonstrated that it is well tolerated and a number of patients achieved stabilisation of their disease. 9 The combination of PLD and temozolomide is appealing given the documented efficacy of temozolomide coupled with the preclinical and clinical data supporting pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of GBM. A phase I study of PLD and temozolomide in patients with advanced cancer demonstrated that the regimen was well tolerated and recommended a phase II dose of PLD 40mg/m2 day one and temozolomide 200mg/m2 days 1-5 every four weeks.11 We have previously published a phase II pilot study of temozolomide and PLD in recurrent GBM. Our data demonstrated good tolerability, modest myelosuppression, and an objective response rate of 19% in 22 patients.12 More striking were the high disease stabilisation rate of 50% and six month progression free interval in 32% of patients. In view of the apparent efficacy of the combination in the 5 recurrent setting, we chose to evaluate the combination of PLD and temozolomide in the adjuvant setting. 6 Patients and Methods Patient Eligibility Eligible patients were >18 years old with histologically proven GBM. All patients had completed concurrent irradiation and temozolomide chemotherapy, and were planning to continue with adjuvant temozolomide treatment as per current approved indications. Patients were not required to have residual disease on a post-radiation scan. Eligibility criteria included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) 02, serum creatinine 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, total granulocyte count > 1500/l; platelet count > 100,000/l, AST 2.5 times the upper limit of normal and total bilirubin within normal limits. Patients must have received 60Gy in 30 fractions of conformal radiotherapy, recovered from the toxicity and completed radiotherapy at least 3 weeks before protocol entry. Corticosteroid doses needed to be stable for one week prior to entry and effective contraceptive measures were practiced. Patients were excluded if they received prior adjuvant chemotherapy other than temozolomide during whole-brain irradiation. Exclusion criteria included prior hypofractionated radiotherapy, patients with clinical evidence of cardiac failure, pregnant or breast feeding women, patients who had not recovered from surgery, those with severe intercurrent illnesses, exposure to other investigational agents within four weeks and during study. Prior use of biodegradeable carmustine wafers was not permitted. Patients must have signed an institutionally approved Committee on Human Research consent form. Study Design This study was a multi-institutional, prospective, open label phase II study. Patients were treated with intravenous PLD at a dose of 40mg/m2 on day one and oral temozolomide at an initial dose of 150mg/m2 increasing to 200mg/m2 on days 1 to 5 for cycle 2 if tolerated. Doses were based on actual body weight but capped at a body surface area of 2.0m2. Treatment commenced between three and six weeks after completion of combined chemoradiotherapy, with a recommended start date four weeks after completion. The start of treatment could be delayed for a maximum of six weeks after combined treatment until adequate hematological recovery. 7 PLD was diluted in 100 ml 5% dextrose with the initial infusion being administered more slowly because of the prior reports of acute reactions to the first dose. Five percent of the total dose was given over 15 minutes, and if this rate was tolerated, the infusion rate was doubled. The remaining infusion was completed over 60 minutes for a total infusion time of 90 minutes. Further courses of PLD could be infused over an hour if no reactions occurred during the first dose. If the patient experienced an infusion reaction, the infusion was ceased, and appropriate premedications such as an antihistamine and/or corticosteroids were given. The infusion was then recommenced at a lower rate. Temozolomide was administered orally on wakening in a fasting state, with all doses being rounded up to the nearest 5mg to accommodate capsule strength. Treatment with PLD and temozolomide was administered every 28 days up to a planned total of six cycles, or until disease progression or dose-limiting toxicity occurred. Toxicity and dose modifications were based on National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0. Criteria for retreatment were an absolute neutrophil count (ANC)>1500 cells/dl, platelet >100,000/dl, hemoglobin >10 g/dl, liver function test values <2 times the upper limit of normal, creatinine <1.5 times the upper limit of normal, total bilirubin within normal limits, and all other toxicity resolved to baseline or Grade one except palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia where specific dose delays were included in the protocol. ( Dose Modifications The nadir ANC or platelet count on Day one was used to determine the doses of temozolomide and PLD administered for subsequent cycles. For patients with nadir ANC of 500 to 999 cells/dl and nadir platelet count of 50 to 74,999 cells/dl or nadir platelet count of 25 to 49,999 cells/dl alone, temozolomide and PLD were both reduced by 25%. Both drugs were reduced by 50% if the nadir ANC was less than 500 cells/dl or nadir platelet count was less than 25,000 cells/dl. Treatment was delayed by a week if patients experienced grade 2 palmar-plantar toxicity. PLD was reduced by 25% if grade one toxicity persisted after a two week delay. If grade three or four toxicity persisted beyond two weeks, patients discontinued PLD and continued temozolomide if clinically indicated. 8 Treatment was withheld for all grades three and four non hematological toxicity, until the toxicity improved to grade one or less, and both PLD and temozolomide doses were reduced by 25%. Patients who developed grade 4 toxicity were taken off study. Patients received a 5-hydroxytryptamine serotonin antagonist at the same time as they took temozolomide and 8mg of intravenous dexamethasone as an antiemetic prior to the administration of PLD. Patient Evaluation All patients who received at least one course of chemotherapy were eligible for response evaluation. Patients who did not have residual disease post-irradiation were not included in the response efficacy endpoint but were eligible for all other endpoint estimations: time to disease progression, overall survival and toxicity. (including stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD)). Patients who did have evaluable residual disease on a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging study (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan (for patients with medical contraindication for MRI) were eligible for all endpoint estimations including response rate (CR and PR). Clinical examination, performance status evaluation, neurological examination and hematological and clinical chemistry tests were performed monthly. Tumour status was determined with an MRI performed every three months and evaluated by an independent radiologist using the MacDonald criteria.13 CR was defined as the disappearance of all enhancing tumor on MRI at least one month apart, discontinuation of steroids, and neurologically stable. PR was at least 50% reduction in the size of enhancing tumor according to the MacDonald criteria maintained for at least one month, steroids stable or reduced and neurologically stable or improved. PD was at least 25% increase in the size of enhancing tumor according to MacDonald criteria or any new tumor on MRI or a neurological assessment of “definitely worse”, and steroids stable or increased. All other assessments were considered SD. Statistical Methods This study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PLD used in combination with temozolomide in the treatment of GBM following concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was six-month progression free survival from the time of first cycle of temozolomide 9 and PLD. Sample size was based on the Optimal design proposed by Simon for a two-stage Phase II trial.14 Assuming a 6-month PFS of 40% for adjuvant temozolomide alone and a PFS6 of less than 50% for the combination was considered of no interest, then a total of 40 patients would allow exclusion of a 50% 6-month PFS rate if fewer than 26 of the 40 patients remained progression-free at 6 months, with α = 0.10 and β = 0.10. The planned interim analysis occurred after 21 patients had been enrolled and followed for at least 6 months by which time all 40 patients had already been recruited. Nevertheless, the criterion for trial continuation was met. 10 Results Patient Characteristics Forty patients were enrolled from four Australian sites between April 2007 and August 2008. Six patients did not have residual disease on post radiation MRI and were therefore not included in the response efficacy endpoint (Table 2) but were included in time to disease progression. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients had completed concurrent irradiation with 60 Gray in 30 fractions and temozolomide chemotherapy and planned to continue with adjuvant temozolomide as part of the study. The median age was 53 years (range 24-76 years). There were 29 males (73%) and 11 females (27%). Most patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 (53%) or one (40%). The tumours were mainly in the temporal lobe (38%) and frontal lobe (35%). The median duration of radiotherapy was six weeks and the median number of weeks from completion of radiation to commencement on study was four weeks (range one-eight weeks). The median number of cycles of treatment delivered was six cycles (range one-six). Response Rates, Disease Progression and Overall Survival Table 2 summarizes the response to therapy among the 34 evaluable patients. One patient achieved a CR (3%) and none had a PR. The median duration of response was 11.7 months. Of the remaining patients 28 (82%) had SD and five patients (15%) had disease progression. Among all 40 patients, the median follow-up time was 14.8 months (range 1.2- 20.8 months). At the time of analysis, 35 patients had progressed (88%). Two patients withdrew from the study prior to completing the six months of follow-up and three patients remain progression free. The median time to progression (TTP) was 6.2 months (95%CI 5.6-8.0 months). The six month PFS was 58% (95%CI 4172%). At last analysis, 32 patients were alive and eight (20%) were dead. The median overall survival was 13.4 months (range 1.2 - 20.9 months). Figures 1 and 2 show Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS respectively. 11 Toxicity Treatment related adverse events are listed in Table 3. Overall the combination was well tolerated, and there were no treatment related deaths. Haematological toxicity included grade 3 neutropenia in three patients (9%), and there was one documented episode of febrile neutropenia. Two patients developed pneumocyctis carinii pneumonia in association with lymphopenia but without neutropenia. There was no grade 3 thrombocytopenia. Treatment related grade 3 non-haematologic toxicity included: palmar-plantar syndrome in two patients (6%), mucositis in one patient (3%) and a hypersensitivity reaction to PLD in one patient (3%). The most common grade 1 or 2 treatment related non-haematologic toxicities observed were rash, lethargy, nausea, vomiting and mucositis. Two patients received only one cycle of therapy. For the remaining patients, 11 (29%) required dose reductions of PLD and ten (26%) required dose reductions of temozolomide. Dose delays were necessary in 16 patients (40%) and 15 patients (38%) due to PLD and temozolomide related toxicity respectively. 12 Discussion The value of conventional chemotherapy for malignant gliomas has been modest and GBM has been considered refractory to most cytotoxic agents. 15, 16 Occasional responses have been documented but these have generally been short-lived with the rapid emergence of resistance. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) has been a major obstacle to the effective delivery of chemotherapy, especially to the infiltrating component of the tumour that is intercalated with normal brain parenchyma. 17, 18 Usually only lipophilic molecules such as the nitrosureas can cross the BBB. The use of PLD has been of interest for several reasons. First, its ability to cross the blood brain barrier more effectively than conventional chemotherapy, given its lipophilic nature, makes it appealing in this tumor. A Phase II evaluation of a novel morphalino-anthracycline, MX-2 has been previously reported that demonstrated preclinical evidence of improved blood brain barrier penetration and proved to be active and well tolerated in patients with high grade gliomas.19 Doxorubicin has been noted to be effective in glioma cell lines and tumour models but its activity is curbed by low lipid solubility and inability to cross the BBB. Secondly, the toxicity of profile of PLD is more favourable than doxorubicin, in particular with regards to hand-foot syndrome and stomatitis. Third, Fabel et al reported significant and prolonged disease stabilisation with PLD in malignant glioma.20 The combination of temozolomide and PLD was chosen given the established role of temozolomide in the treatment of GBM. Temozolomide has demonstrated survival benefit and modest toxicity. In a phase 1 study, Volm et al demonstrated that the combination was safe and could be given at full dose. In a Phase II study conducted by our group, we concluded that the combination of temozolomide and PLD was well tolerated, resulted in a modest objective response rate, but had encouraging disease stabilization in the treatment of recurrent GBM. Of interest, the six month PFS was 32% that compared favourably with data from studies of single agent temozolomide in recurrent GBM in which the six month PFS was 20%.21-24 13 This current study demonstrates that the combination of PLD and temozolomide is well tolerated but does not appear to add significant clinical benefit in the treatment of newly diagnosed GBM. We reported a 6PFS of 57.9% and a median OS of 13.4 months. The objective radiological response rate to treatment was 3% which was inferior to that achieved in our study in recurrent disease, where a response rate of 19% was noted.25 The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC) 26981 trial reported an improved median survival (14.6 months) and 2-year survival of 26.5% with adjuvant radiotherapy and temozolomide as compared with radiotherapy alone.4 This has recently been updated with 5 year overall survival of 9.8 months.5 Although the survival may appear to be similar to our data, clearly added to this is a significant bias in outcome in our cohort as these patients were those who had successfully completed concurrent therapy and were well enough to be considered for the 6 months of temozolomide. In the EORTC 26981 database, patients who completed the concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide component of their treatment and were about to embark on the six months of temozolomide therapy had a 6PFS of 50% and a median OS of 14.1 months (Roger Stupp, personal communication). In the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)/EORTC study 26052 intensified temozolomide trial, where patients are also randomised before starting their six months of post-irradiation temozolomide, a median survival of 14 months was taken as null hypothesis and 17.5 months as alternative hypothesis. There are other limitations to our study. First, like many studies in high grade glioma, we chose six month PFS as the primary end point of our study. There is increasing evidence that 6PFS is a strong predictor of survival, and 6PFS is a valid end point for trials of therapy for recurrent malignant glioma.26 However, there continues to be difficulty in defining radiological response especially post radiotherapy.27 In addition, we cannot discount the possibility that patients assessed as progressing may have experienced radiological pseudo-progression. Second, we added PLD only to the post-irradiation component of the EORTC protocol. Most current studies add the novel agent to the concurrent irradiation/chemotherapy component of the standard EORTC protocol. However, we were concerned about additional toxicity associated with the potential interaction between PLD and radiotherapy. 14 Third, MGMT methylation status was not evaluated and this may impact on the interpretation of the results. Finally, the numbers in our study were relatively small and would be insufficient to exclude a modest incremental beneficial effect of the combination. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the combination of temozolomide and PLD in the adjuvant treatment of GBM post radiotherapy is well tolerated but does not provide significant additional benefit when compared to the current standard of care. Although there has been marked improvement in the survival of these patients with the addition of temozolomide to radiotherapy, the survival of these patients remains poor. With the advent of new targeted therapies, further investigation of these new agents in combination with the standard treatment should be explored to improve the outcomes of patients with GBM given the lack of efficacy with conventional chemotherapy. 15 Acknowledgments This investigator-initiated trial was supported by an unrestricted grant from Schering-Plough and by Cancer Australia. The study was conducted and analysed independently of S-P and CA. 16 References 1. Louis DN OH, Wiestler OD. The 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. In. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007. 2. CBTRUS 2008 statistical report: primary brain tumors in the United States. 1998-2002. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States, 2000-2004 2008; (Accessed July 7, 2008, at http://www.cbtrus.org/ reports/2007-2008/2007report.pdf.). 3. Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, et a. cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2002; 52: 23- 47. 4. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 987-996. 5. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 459-466. 6. Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, et a. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer research 1994; 54: 987-992. 7. Uziely B, Jeffers S, Isacson R, et a. Liposomal doxorubicin: antitumor activity and unique toxicities during two complementary phase I studies. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1777-1785. 8. Siegal T, Horowitz A, Gabizon A. Doxorubicin encapsulated in sterically stabilized liposomes for the treatment of a brain tumor model: biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy. Journal of neurosurgery 1995; 83: 1029-1037. 17 9. Hau P, Fabel K, Baumgart U, et a. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-efficacy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Cancer 2004; 100: 1199-1207. 10. Sharma US, Sharma A, Chau R I, et a. Liposome-mediated therapy of intracranial brain tumors in a rat model. Pharmaceutical research 1997;14:992-998. 11. Volm M, Oratz R, Pavlick A, et a. A phase I study of liposomal doxorubicin and temozolomide in patients with advanced cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 19: 2000 (abstract). 12. Chua SL, Rosenthal MA, Wong SS, et a. Phase 2 study of temozolomide and Caelyx in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncology 2004; 6: 38-43. 13. Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr., Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8: 1277-1280. 14. Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1989; 10: 1-10. 15. Fine HA, Dear KB, Loeffler JS, Black PM, Canellos GP. Meta-analysis of radiation therapy with and without adjuvant chemotherapy for malignant gliomas in adults. Cancer 1993; 71: 2585-2597. 16. Stewart LA. Chemotherapy in adult high-grade glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 12 randomised trials. Lancet 2002; 359: 1011-1018. 17. Walker MD, Alexander E, Jr., Hunt WE, et al. Evaluation of BCNU and/or radiotherapy in the treatment of anaplastic gliomas. A cooperative clinical trial. J Neurosurg 1978; 49: 333-343. 18. Randomized trial of procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in the adjuvant treatment of high-grade astrocytoma: a Medical Research Council trial. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 509-518. 18 19. Clarke K, Basser RL, Underhill C, et a. KRN8602 (MX2-hydrochloride): an active new agent for the treatment of recurrent high-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2579-2584. 20. Fabel K, Dietrich J, Hau P, et al. Long-term stabilization in patients with malignant glioma after treatment with liposomal doxorubicin. Cancer 2001; 92: 1936-1942. 21. Brada M, Hoang-Xuan K, Rampling R, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme at first relapse. Ann Oncol 2001; 12: 259-266. 22. Harris MT, Rosenthal MA, Ashley DL, Cher L. An Australian experience with temozolomide for the treatment of recurrent high grade gliomas. J Clin Neurosci 2001; 8: 325-327. 23. Stupp R, Gander M, Leyvraz S, Newlands E. Current and future developments in the use of temozolomide for the treatment of brain tumours. Lancet Oncol 2001; 2: 552-560. 24. Yung WK, Prados MD, Yaya-Tur R, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of temozolomide in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma at first relapse. Temodal Brain Tumor Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2762-2771. 25. Chua SL, Rosenthal MA, Wong SS, et al. Phase 2 study of temozolomide and Caelyx in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol 2004; 6: 38-43. 26. Lamborn KR, Yung WK, Chang SM, et a. Progression-free survival: an important end point in evaluating therapy for recurrent high-grade gliomas. Neuro-oncology 2008; 10:162-170. 27. Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high- grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol; 28: 1963-1972. 19 Table 1: Patient Characteristics Characteristics Eligible patients Sex Male Female Median age (range) ECOG performance status 0 1 2 40 patients 29 (73%) 11 (27%) 53 years (24-76 years) 21 (53%) 16 (40%) 3 (7%) Median time from radiotherapy (range) 4 weeks (1-8 weeks) Median cycles of chemotherapy (range) 6 (1-6) Neurological deficit at registration 14 (35%) Residual disease on MRI 34 (85%) 20 Table 2: Response rates in 34 patients with evaluable disease * Response Number of Patients (%) Complete response 1 (3%) Partial response 0 (0%) Stable disease 28 (82%) Progressive disease 5 (15%) *Six (15%) of the 40 patients were not evaluable for response 21 Table 3. Treatment related Grade 3 toxicities (40 patients) Grade 3 (%) Thrombocytopenia 0 (0%) Neutropenia 3 (9%) Anaemia 0 (0%) Hand-foot syndrome 2 (6%) Nausea/Vomiting 0 (0%) Mucositis 1 (3%) Reaction to Caelyx 1 (3%) 22 Figure 1. Progression free survival at 6 months 23 Figure 2. Overall survival