Listening to the Community Voices

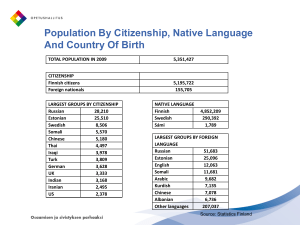

advertisement