Table 1

advertisement

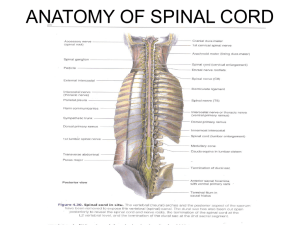

Table 6. Summary of literature review4-114. Dural Tears Incidence of intraoperative durotomies ranges from 3.1 % to 15 %. 4-13 Primary closure whenever possible is the favored method of management and often leads to an excellent result with no postoperative sequelae or effect on the long-term outcome of the primary pathology the .4-6,14 Patients with persistent immediate postoperative symptoms typically have an extended course in hospital; however these patients will also achieve symptom resolution with appropriate treatment (all of our cases). However, atypical complications, such as a subdural hematoma which may have significant longer-term sequelae can occur with uncontrolled leaks.15-17 Incidental durotomy is a frequent issue in medical malpractice litigations.18 o Based on our results we conclude that it is not related to poor outcome if a repair was achieved and there is no clinical evidence of an ongoing CSF leak. This study shows that the incidence of dural violation over the full spectrum of complex spinal surgery is frequent (8% in our series), however, when appropriately treated is asymptomatic in the majority of patient. Spinal Instrumentation Incidence of instrumentation related AE and complications is highly variable (range 0-55%), and dependent on a variety of factors.8,11,13,19, 20-44 The majority of reported instrumentation related AE do not lead to complications. o This is best exemplified by the literature on pedicle thoracic and lumbosacral pedicle screw fixation (misplacement rates (AE) ranging from 3 to 55% in the lumbar and thoracic spine).37,42,45-60 o Clinical sequelae (complications) related to pedicle screw misplacement are currently reported from 0 to 7%.33,36,42,45-56 Review of the literature and the results (Table 4) of this study show that in the hands of experienced surgeons, recognition of suboptimal instrumentation (AE) intraoperative or postoperatively with appropriate correction will lead to a low incidence of instrumentation related complications. Massive Blood Loss (> 5000mls, i.e. one average blood volume) The clinical consequences range from none to life threatening. 61-67 Massive blood loss can lead to negative cardiac, pulmonary or renal effects, coagulopathy, transfusions, and procedural (e.g. unable to complete) consequences. In this series there was a 1.42% incidence. o One patient that had a myocardial infarction (MI) on the fourth postoperative day. o Development of coagulopathy obviously significantly confounds the scenario of massive blood loss. These patients inevitably end up in a vicious cycle of coagulopathy –increased bleeding – obscured operative field with greater difficulty to control bleeding and efficiently progress with the procedure – this leads to further bleeding which perpetuates the coagulopathy – etc. At our institution the large number of high risk complex spinal cases have lead to the routine use of multimodality preoperative and surgical / non-surgical intraoperative blood conservation techniques particularly for cases where > 1000 mls of blood loss is anticipated. In addition to this, one of the key factors in dealing with these cases is early identification (pre- and intraoperatively) of patients at risk for massive blood loss and proactive communication before and during the case between the anaesthesia and the surgical team. From a surgical perspective, simple tricks such as placement of all instrumentation including precontouring of rods prior to the “bloody” portion of the procedure (e.g. osteotomy), early aggressive replacement of coagulation factors at the first clinical sign of reduced clotting in the surgical field (particularly if this occurs before the high risk portion of the procedure) or staging the procedure when ever possible can all have a dramatic effects on reducing the incidence and associated risk of massive bleeding. Anesthesia / Medical A detailed discussion of all anaesthetic or medical AE related to spinal surgery is obviously beyond the scope of this paper. Other then blood loss, the two most common anesthetic challenges specific to spinal surgery are associated with prone positioning and airway management. During the transition from supine to prone positioning there is always the possibility of losing the airway due to displacement of the endotracheal tube. o Even at our center, where 3-4 spinal rooms run daily and established positioning protocols are followed, this AE still occurred in one case (0.14%). o This underscores the need for constant awareness of the airway by not only anaesthesia, but the entire surgical team. o Rapid recognition and correction of this problem is typically very easy without any sequelae. Airway associated events following cervical spinal surgery will forever remain one of the greatest concerns and risk in spinal surgery. The impact of airway problems can be significant not only from a short term perspective, but also a long term perspective and as such command a high degree of vigilance in their prevention, recognition and management.69-71 Anterior Approach The incidence of anterior spinal approach vascular injuries range from 0% to 15.6%. 72-83 There were no arterial injuries in our series. All vein injuries in this series were quickly controlled and repaired primarily with no postoperative consequences (i.e. DVT). Intraoperative vascular lesions are easily recognizable and require prompt vascular control and primary repair whenever possible. In most cases this potentially very significant AE is manageable without any further clinical sequelae. However, if the spine surgeon does not have the proper training in spinal exposures and techniques for vascular control and repair these AE can be life threatening. In this scenario the use of an appropriately trained access surgeon for these procedures is mandatory. Although rare vascular injuries during any posterior procedures are preventable by anatomical awareness and proper surgical techniqe.81,84-87 Vertebral Artery Injuries Clinical consequences may range from a complete absence of symptoms to brain stem infarction and death. The reported incidence of vertebral artery injury during cervical spinal surgery ranges from 0% for lateral mass screws to as high as 14% with the placement of C1-C2 transarticular screws.20,21,23,88-101 The variability of VA course from patient-to-patient and from side-to-side renders one or occasionally both the C1-C2 transarticular pathway(s) unsafe in 10-20% of patients.91,102,103 Incidence of known and suspected VA injuries are ~ 2.4% and 1.7% respectively for C1-2 transarticular screws.104 The risk of neurological deficit from VA injury of 0.2% per patient or 0.1% per screw, and a mortality rate of 0.1%. In the present study there were no injuries related to C1-C2 transarticular screws. For the one suspected and 2 know VA injuries in this series, there were no postoperative symptoms, thus the risk of performing invasive angiography and possible embolization was not warranted. The variability of the VA is well known and with due diligence VA injuries for the most part should be preventable. o As stated by others, the authors feel that it is mandatory to study the location of the VA (preoperative CT with reformats and/or MRI) for planned cervical instrumentation (lateral mass screw placement, C1-C2 transarticular screw placement, C2 pars / pedicle screw placement) or exposures /decompressions (C1 exposure, transoral odontoidectomy, tumors involving the VA and subaxial cervical corpectomy) that place the VA at risk. Modifying or simply not attempting instrumentation where the VA is at obvious high risk of injury is the best way of minimizing this AE. Intraoperatively, clearly defining the anatomy and the use of intraoperative imaging with or with out image-guidance are necessary to minimize VA injury. Esophageal and Pharyngeal Injury Esophageal/pharyngeal injuries are a rare but potential disastrous complication from anterior cervical surgery. Esophageal/pharyngeal injuries that occur acutely at the time of surgery almost always lead to complications, particularly if unrecognized. The majority (> two thirds) are unrecognized at the time of surgery and present in the acute perioperative or late (>6 weeks) postoperative period. 105-113 This AE carries significant morbidity and possible mortality particularly if mediastinitis develops. Management ranges from simple primary repair to esophageal diversion and delayed reconstructed. 114 Consultation with otolaryngologic or thoracic surgery is advisable particularly in cases of esophageal injury. Pharyngeal injuries are managed essentially with the same postoperative protocol as transoral procedures. Obviously early detection (routine inspection of the cervical surface of the esophagus at the end of each case) and aggressive management is paramount in reducing the potential for a poor outcome following this AE. A high index of suspicion should be maintained and appropriate investigations carried out for any patient presenting with infectious type symptoms following cervical spinal surgery. Sterile Field Contamination This AE has or will occur to every surgeon at least once in their careers’ the authors could not identify any specific medical literature on this AE. This is likely a result of the overall very low incidence of this AE which is due to longstanding surgical prepping and draping standards. Contamination of the sterile field may lead to infection and requires appropriate action. Management, depending on the degree of contamination, may range from simple irrigation of the wound to change of the entire surgical set up. Appropriate patient counseling of the AE and the management steps taken as well as any potential risk (if know) and possible symptoms should be carried out. Positioning This type of AE has not been previously reported in the medical literature. No sequelae resulted for these two AE, however the potential for harm is significant. Since this study the authors have instituted a protocol whereby the correct position and the number of fixation pins on the Jackson spinal table are checked and counted by two different individuals (the most senior member of the nursing and surgical team present) prior to positioning or before and after flipping a patient on the Jackson table. It is obviously impossible to completely prevent any such mishaps from occurring, however, failure to institute protocols to prevent such events form occurring again is inexcusable. Surgical Instrument Failure Although this is an AE that has or will occur to every surgeon at least once in their careers’ the authors could not identify any specific medical literature on this AE. Obviously the retained portion of the broken instrument should be retrieved whenever possible. In some circumstances (e.g. deeply imbedded in bone) the process of retrieval may result in more morbidity then leaving the object in-situ. This has to be assessed on an individual basis and intraoperatively is ultimately up to the judgment of the operating surgeon. Appropriate patient counseling of the AE and the management steps taken as well as any potential risk (if know) and possible symptoms should be carried out. Change on Planned Surgery This is also another situation that every surgeon will have to face at some time. In the majority of cases the possibility of potentially not being able to technically achieve a planned procedure is know preoperatively. This is particularly so in revision surgeries were surgeons will often have a second or third plan. In fact, it is typically part of most informed consent that the surgeon may in the event of any unforeseen event have to alter or modify the procedure in order to achieve the desired outcome. The degree of modification is obviously on a per case basis and is dependent on the degree of options discussed preoperatively and the potential added morbidity of the modification. The latter of which is dependent on the judgment of the operating surgeon. As can be seen from the results of this study, this is a rare event, but one that is possible with any surgical procedure.