History Thesis

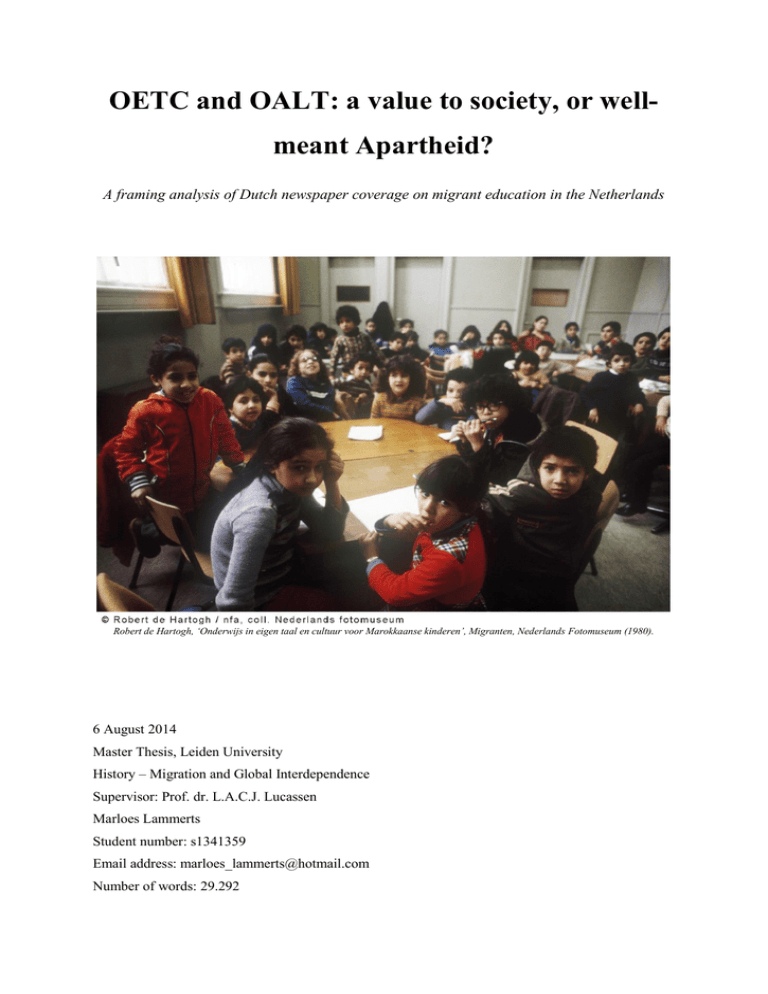

advertisement