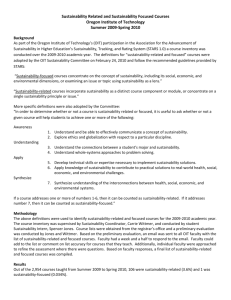

PPT version of slides

advertisement

Intro to non-rational

expectations (learning) in

macroeconomics

Lecture to Advanced Macro class,

Bristol MSc, Spring 2014

Me

• New to academia.

• 20 years in Bank of England, directorate

responsible for monetary policy.

• Various jobs on Inflation Report, Inflation

Forecast, latterly as senior advisor, leading

‘monetary strategy team’

• Research interests: VARs, TVP-VARs,

monetary policy design, learning, DSGE,

heterogeneous agents.

• Also teaching MSc time series on VARs.

Follow my outputs if you are

interested

• My research homepage

• Blog ‘longandvariable’ on macro and public

policy

• Twitter feed @tonyyates

This course: overview

• Lecture 1: learning

• Lectures 2 and 3: credit frictions

• Lecture 4: the zero bound to nominal interest

rates

• Why these topics?

– Spring out of financial crisis: we hit the zero

bound; financial frictions part of the problem; RE

seems even more implausible

– Chance to rehearse standard analytical tools.

– Mixture of what I know and need to learn.

Course stuff.

• No continuous assessment. Assignments not

marked. All on the exam.

• But: Not everything covered in the lectures!

And, if you want a good reference…

• Office hour tba. Email

tony.yates@bristol.ac.uk, skype:

anthony_yates.

• Teaching strategy: some foundations, some

analytics, some literature survey, intuition,

connection with current debates.

• Exams not as hard as hardest exercises.

More course stuff

• All lectures and exercises posted initially on

my teaching homepage. In advance (ie there

now) but subject to changes at short notice.

• Roman Fosetti will be taking the tutorial.

• I’ll be doing 2 other talks in the evening on

monetary policy issues, to be arranged.

Voluntary. But one will cover issues

surrounding policy at the zero bound.

• Feedback welcome! Exam set, so course

content set now. But methods…

Some useful sources on learning

• Evans and Honkapoja (2000) textbook.

• George Evans reading list on learning and

other topics

• George Evans lectures: borrowed from here.

• Bakhshi, Kapetanios and Yates, eg of empirical

test of RE

• Milani – survey of RE and learning

• Ellison-Yates, mis-specified learning by

policymakers

• Marcet reading list

Motivation for thinking about non

rational expectations

• Rational expectations is very demanding of

agents in the model. More plausible to

assume agents have less information?

• Some non-rational expectations models act as

foundational support for the assumption of

rational expectations itself, having REE as a

limit.

• Some RE models have multiple REE. We can

look to non-RE as a ‘selection device’.

Motivation for non-RE

• RE is a-priori implausible, but also can be

shown to fail empirically….

• RE imposes certain restrictions on

expectations data that seem to fail.

• Non RE can enrich the dynamics and

propagation mechanisms in (eg) RBC or NK

models: post RBC macro has been the story of

looking for propagation mechanisms.

Motivation 1: RE is very demanding

• Sargent: rational expectations = Communist

model of expectations (!)

• Perhaps Communist plus Utopian

• What did he mean?

• Everyone has the same expectations

• Everyone has the correct expectations

• Agents behave as if they understand how the

model works

RE in the NK model

kx t e ,t

t E t

t

1

x t E t

x t1

it E t

e x,t

t

1

it

it1

t

xx t

NB the expectation is assumed to be the true, mathematical expectation

The computational demands of RE

t

Yt

xt

e ,t

St

it

e x,t

Et

Yt1 AS t

it1

find AS t

such that E

Y

AS t

AS t

Method of undet coeff: where ‘E’ appears, substitute our conjectured linear function

of the state, then solve for the unknown A

REE: when agents use a forecasting function, their use of it induces a situation where

exactly that function would be the best forecast.

So agents have to know the model exactly, and compute a fixed point!

If you find this tricky, think of the poor grocers or workers in the model!

Motivation 2, ctd: empirical tests of

implications of RE often fail

Collect data on inflation expectations;

Compute ex post forecast errors

t

1 E t

t

1 e E,t

e E,t

X t

0

Coefficients

should not be

statistically

different from

zero. Betahat

includes

constant.

Regress errors on ANY

information available to agents

at t

Take the test to the data

• Bakhshi, Kapetanios and Yates ‘Rational expectations

and fixed event forecasts’

• Huge literature, going back to early exposition of

theory by Muth, so this is but one example.

• Survey data on 70 fund managers compiled by Merril

Lynch

• Regression of forecast errors on a constant, and past

revisions

• Regression of revisions on past revisions

• Fails dismally!

Source: BKY (2006), Empirical Economics, BoE wp

version, no 176, p13.

Squares are outturns. Lines approach them in

autocorrelated fashion. Revisions therefore autocorelleated.

Motivation 2: learning as a foundation

for RE

• If we can show that RE is a limiting case of some

more reasonable non rational expectations

model, RE becomes more plausible

• We will see that some rational expectations

equilibria are ‘learnable’ and some are not.

Hence some REE judged more plausible than

others.

• Policy influences learnability, hence some policies

judged better than others.

Motivation for studying learning

• Learning literature treats agents as like

econometricians, updating their estimates as

new data comes in. [‘decreasing gain’] And

perhaps ‘forgetting’ [‘constant gain’].

• So drop the requirement that agents have to

solve for fixed points! And require them only

to run and update regressions.

• A small step in direction of realism and

plausibility.

• Cost: getting lost in Sims’ ‘wilderness’.

Stability of REE, and convergence

of learning algorithms

• General and difficult analysis of the two

phenomena. Luckily connected.

• Despite all the rigour, usually boils down to

some simple conditions.

• But still worth going through the background

to see where these conditions come from.

• Lifted from Evans and Honkapohja (2001),

chs1 and 2

Technical analysis of stability and

expectational dynamics

• Application to a simple Lucas/Muth model.

• Find the REE

• Then conjecture what happens to

expectations if we start out away from RE.

• Does the economy go back to REE or not?

• Least squares learning, akin to recursive least

squares in econometrics.

• Studying dynamics of ODE in beliefs in

notional time.

Lucas/Muth model

q t q

p t E t1 p t t

m t v t p t q t

m t m u t w t1

1. Output equals natural rate plus something times price

surprises

2. Aggregate demand = quantity equation.

3. Money (policy) feedback rule.

Finding the REE of the Muth/Lucas

model

• 1. Write down reduced form for prices.

• 2. Take expectations.

• 3. Solve out for expectations using guess and

verify.

• 4. Done.

• NB this will be an exercise for you and we

won’t do it here.

Finding the REE of the Muth/Lucas

model

p t E t1 p t w t1 t

0 1,

1

1

Reduced form of this model in terms of prices.

p t a bw t1 t

a

,b

1

1

Rational expectations

equilibrium, with expectations

‘solved out’ using a guess and

verify method.

Towards understanding the Tmapping in learning that takes PLM

to ALM

p t E t1 p t w t1 t

Reduced form of LM model.

p t a 1 b

1 w t1

Forecaster’s PLM1

p t

a 1

b

w t1 t

1

ALM1 under this PLM1

p t

2 a 1

2 b

w t1 t

1

ALM2 under PLM2=f(ALM1)

Repeated substitution expressed as

repeated application of a T-map

T

a 1 , b 1

a 1 , b

1

T

a 1 , b

2 a 1 , 2 b

1

1

T is an ‘operator’ on a function (in this case our agent’s

forecast function) taking coefficients from one value to

another

T2

a 1 , b 1

2 a 1 , 2 b

1

Repeated applications written as powers [remember

the lag operator L?

Verbal description of T:

‘take the constant, times by alpha and add mu; take the

coefficient, times by alpha and add delta’

Will our theoretician ever get to

the REE in the Muth-Lucas model?

T

a 1 , b 1 ?

limn T

a 1 , b 1 ?

To work out formally whether imaginary theoretician will ever get

the REE, we are asking questions of these expressions in T above.

Answer to this depends on where we start. On certain properties

of the model.

Sometimes we won’t be able to say anything about it unless we

start very close to the REE.

Matlab code to do repeated

substitution in Muth-Lucas

Progression of experimental

theorist’s guesses in the MuthLucas model

0.35

0.3

0.25

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

0.9

0.8

0.6

0.5

0.4

This is for alpha=0.25<1; charts for a,b(1),b(2) respectively, green lines

plot REE values.

What happens when alpha>1?

100

50

0

-50

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

2

0

-2

-4

4

2

0

-2

Coefficients quickly explode. Agents never find the REE.

Because coefficients explode, so will prices.

Since prices didn’t explode (eg in UK) we infer not realistic, hoping for

the best

Iterative expectational stability

• Muth-Lucas model is ‘iterative expectational

stable’ with alpha<1.

• REEs that are IE stable, more plausible, ie

could be found by this repeated substitution

process. (Well, a bit more!)

• Why is alpha<1 crucial?

• Each time we are *by alpha. So alpha<1

shrinks departures (caused by the adding bit)

from REE.

Repeated substitution, to

econometric learning

• Perhaps allowing agents to do repeated

substitution is too demanding.

• Instead, let them behave like econometricians

– Trying out forecasting functions

– Estimating updates to coefficients

– Weighing new and old information appropriately

Least squares learning recursion

for the Muth-Lucas model

p

p

E t1 p t

a t1 , b t1

, z t1

1, w t1

t1 z t1 , t1

p t E t1 p t w t1 t

1

t t1 t 1 R

z

p

t

t

1

t

t1 z t1

Rt Rt1 t 1

z t1 z

t1 Rt1

Beliefs stacked in phi.

Decreasing gain. As t gets large, rate of change of phi gets small.

Phi: ‘last period’s, plus this periods, times something proportional to the

error I made using last period’s phi’

R: moment matrix. Equivalent to inv(x’x) in OLS. Large elements

means imprecise coefficient estimate, means don’t pay too much

attention if you get a large error this period.

Close relative: recursive least squares

in econometrics

e .t

t

t1

X X1 X Y

X

t , t 2, . . . T

t1 , Y

Suppose we have an AR(1) for

inflation

The OLS formula is given by

this

1

t t1 t 1 R

t

t1

t1

t1

t

Rt Rt1 t 1

t1

t1 Rt1

Recursive least squares

can be used to compute

the same OLS estimate as

the final element in this

sequence

Example of recursive least squares

0.885

0.88

rhohat value

0.875

0.87

0.865

0.86

0.855

0.85

0.845

0

DGP : p t p t1 z t

1 p 1 . . . p 500

R1 R

p 1 . . . p 500

0. 85

z 0. 2

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Periods after train samp

400

450

500

Rhohat initialised at training sample estimate

Slowly updates towards the full sample estimate,

which is fractionally above the true value

Consistency properties of OLS illustrated by the

slow convergence.

RLS useful in computation too, saves computing

large inverses over and over in update steps

Matlab code to do RLS

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

%program to illustrate recursive least squares in an autogregression.

%MSc advanced macro, use in lecture on learning in macro

%formula in, eg Evans and Honkapohja, p33, 'Learning and Epectations in

%Macro', 2000, ch 2.

%nb we don't initialise as suggested in EH as there seems to be a misprint.

%see footnote 4 page 33.

clear all;

%first generate some data for an ar(1): p_t=rho*p_t-1+shock

samp=1000;

%set length of artificial data sample

rssamp=500;

%post training sample length

p=zeros(samp,1);

%declare vector to store prices in

p(1)=1;

%initialise the price series

sdz=0.2;

%set the variance of the shock

rho=0.85;

%set ar parameter

z=randn(samp,1)*sdz;

%draw shocks using pseudo random number generator in matlab

for i=2:samp

p(i)=rho*p(i-1)+z(i);

end

%loop to generate data

RLS code/ctd…

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

%now compute recursive least squares.

rhohat=zeros(rssamp,1);

%vector to store recursive estimates of rho

y=p(2:rssamp-1);

x=p(1:rssamp-2);

%create vectors to compute ols on artificial data

rhohat(1)=inv(x'*x)*x'*y;

R=x'*x;

%initialse rhohat in the rls recursion to training sample

%initialise moment matrix on training sample

for i=2:rssamp

%loop to produce rls estimates.

x=p(rssamp+i-1);

y=p(rssamp+i);

rhohat(i)=rhohat(i-1)+(1/i)*inv(R)*x*(y-rhohat(i-1)*x);

R=R+(1/i)*(x^2-R);

end

y=p(2:samp);

x=p(1:samp-1);

%code to create full sample ols estimates to compare

rhohatfullsamp=inv(x'*x)*x'*y;

rhofullline=ones(rssamp,1)*rhohatfullsamp;

time=[1:rssamp];

%create data for xaxis

plot(time,rhohat,time,rhofullline)

%plot our rhohats and full sample rhohat

title('Example of recursive least squares')

xlabel('Periods after train samp')

ylabel('rhohat value')

Learning recursion in terms of the

T -mapping

t

at

bt

p t T

t1 zt1 t , zt

1, w

t

1

t t1 t 1 R

z

T

t1 t1 t

t z t1

t1

Rt Rt1 t 1

z t1 z

t1 Rt1

Crucial step here noticing that we can rewrite in terms of the T-mapping.

Now dynamics of beliefs related to T()-() as before.

• Just as with our repeated substitution, and

study of iterative expectational stability…

• The learning recursion involves repeated

applications of the T-mapping.

• So rate of change of beliefs will be zero if T

maps beliefs back onto themeslves, or T()()=0.

Estability, the ODE in beliefs

d

d

ap

b

p

T

ap

b

p

ap

bp

Rough translation: the rate of change of beliefs in notional

time is given by the difference between beliefs in one period,

and the next, ie between beliefs and beliefs operated on by the

T-map, or the learning updating mechanism.

da p

1a p

d

p

db i

p

1b i

d

ODE’s for our Muth/Lucas

model

Estability conditions

d

d

ap

b

p

T

ap

b

p

ap

b

p

1

T

1 0

a1

0 1

b1

1

0

a1

0

1

b1

Stability depends on eigenvalues of transition matrix <1

Transition matrix is diagonal, so eigenvalues read off the

diagonal. Both=alpha-1. So alpha<1.

We still need to dig in further and ask why the RLS system

reduces to this condition [which looks like the iterative

expecational stability condition].

Foundations for e-stability analysis

p t T

t1 zt1 t , zt

1, w

t

Rewrite the PLM

using the T-map

1

t t1 t 1 R

z

T

t1 t1 t

t z t1

t1

Rt Rt1 t 1

z t1 z

t1 Rt1

Learning recursion with PLM in terms of the T-map.

If T()=(), then 1st equation is constant (in expectation),

because the second term in this first equation then gets

multiplied by a zero.

Likewise if R is very ‘large’ [it’s a matrix], coefficients

won’t change much. Here large means estimates

imprecise.

Rewriting the learning recursion

1

t t1 t 1 S

z

z

T

t1 t1 t

t1 t1 t1

S t S t1 t 1

t

z t1 z

t1 S t1

t 1

Here we rewrite the system by setting R_t=S_t-1

It will be an exercise to show that the system is written like

this and explain why.

t t1 t Q

t, t1 , X t

t

t , Rt

X t z t1 , t

And we can write the system more generally and compactly like

this. Many learning models fit this form. We are using the

Muth-Lucas model, but the NK model could be written like this,

and so could the cobweb model in EH’s textbook.

Deriving that estability in learning

reduces to T()-()

t t1 t Q

t, t1 , X t

d

d

h

Dh

h

limt EQ

Expectation taken over the state variables X.

Why? We want to know if stability holds for all

possible starting points.

Stability properties will be inferred from linearised

version of the system about the REE [or

whichever point we are interested in].

Muth-Lucas system already linear, but in general

many won’t be.

Estability

If all eigenvalues of this derivative or Jacobian

matrix have negative real parts, system locally

stable.

Dh

1

Q

t, t1 , X t S

z

T

t1 t1 t

t1 z t1

t1

Qs

t, t1 X t vec

t

zt z

t S t1

t 1

1

h

, Slim ES

z

T

t1 t1 t

t1 z t1

t1

t

hS

, Slim E

t

t

zt z

t S t1

t 1

Unpack Q: we will

show that stability is

guaranteed in second

equation.

Expectations taken over X,

because we are looking to

account for all possible

trajectories.

Reducing and simplifying the

estability equations

This period’s shock uncorrelated

with last period’s data

Ez t1 t 0

t

lim

1

t t 1

Ez t z

t Ez t1 z t1

1 0

0

M

d

1

S

T

t1 M

d

hS

, S dS M S

d

h

, S

TR 1 entry as z includes constant.

Bottom right is variance of w

0s because w not correlated with

1!

d

T

d

hS

, S dS 0

d

h

, S

We can get from the LHS pair to the RHS pair because S tends to

M from any starting point.

Recap on estability

• We are done! Doing what, again?!

• That was explaining why the stability of the

learning model, involving the real-time

estimating and updating, reduces to a

condition like the one encountered in the

repeat-substitution exercise, involving T()-().

• And in particular why the second set of

equations involving moment matrix vanishes.

Remarks about learning literatures

•

•

•

•

Constant gain

Stochastic gradient learning

Learnability, determinacy, monetary policy

Learning by policymakers, or two-sided

learning

• Learning using mis-specified models, RPEs, or

SCEs.

• Analogy with intra period learning, solving in

nonlinear RE eg RBC models

Constant gain

1

t t1 R

z

z

T

t1 t1 t

t1 t1

t

Rt Rt1

z t1 z

t1 Rt1

We replace inv(t) with gamma, so weight on update term is constant.

Recursion no longer converges to limiting point, but to a distribution.

Has connections with kernel (eg rolling window) regression.

Larger gain means more weight on the update, more weight on recent

data, more variable convergent distribution.

Stochastic gradient learning

t t1 zt1

z

T

t1 t1 t

t1

Set R = I.

Care: not scale or unit free.

Like OLS without inv(X’X),

But eliminates possibly explosive recursion for R.

Loosens connection with REE limit of normal learning recursion.

Projection facilities

LS learning recursions with constant gain can explode without PFs.

Example below.

Marcet and Sargent convergence results also rely on existence of

suitable PFs.

1. computeRt Rt1

z t1 z

t1 Rt1

p

1

2. compute t t1 R

z

T

t1 t1 t

t z t1

t1

p

p

3. if abs

max

eig

t

1, t t , else t t1

4. compute E t

, zt

5. t t 1

6. goto 1.

So a projection facility is something that says: don’t update if it looks

like exploding.

Learnability and determinacy

it

x x t , 1

t

See EH, Bullard and Mitra, Bullard and Schaling.

This condition, the `Taylor Principle’ [note he has a rule, a curve and

a principle named after him!] guarantees uniqueness of REE in the

NK model.

Referred to as ‘determinacy’.

Means: only one value for expectations given value of fundamental

shocks (like technology, monetary policy, demand).

Absence implies possibility for self-fulfilling expectational shocks.

We will see this in the lecture on the zero bound.

Also guarantees ‘learnability’ and e-stability of REE.

Two-sided learning

• So far we have just considered private sector

learning as a replacement for the RE operator

in the Muth/Lucas and the NK model.

• Obviously we could consider a policymaker

learning too.

• A policy decision [eg some pseudo optimal

policy] depends on knowledge of structural

parameters gleaned from a regression,

updated each period…

Learning with misspecification

• Once we free ourselves from RE, why restrict

ourselves to agents only deploying regressions

that embrace the functional form of the REE?

• After all, much controversy about the

functional form of the actual economy!

• Such models clearly don’t have REE. But they

can have equilibria:

• ‘Restricted perceptions’ or ‘Self-confirming

equilibria’

• Eg Cho, Sargent and Williams / Ellison-Yates

Sargent: Conquest of American

inflation

• Fed thinks that higher inflation buys

permanently lower unemployment.

• In reality, only inflation-surprises lower

unemployment.

• Fed re-estimates mis-specified Philips Curve

each period.

• Most of time in high inflation mode, with

periodic escapes to low inflation.

Ellison-Yates

• How low inflation regime also means low

variance, and high inflation regime means

high variance.

• When time is good for trying to lower long run

u, it’s also good for using inf to smooth shocks

in u

• Literature on ‘Great moderation’ (now

vanished) emphasised low frequency changes

in second moments of macro variables.

• Ellison-Yates GM=temporary escape.

Inter period learning, intra-period

learning, PEA

• Intra-period learning as an analogous way to

say something about equilibrium plausibility.

See, eg, Blake, Kirsanova and Yates/Dennis

and Kirsanova

• Idea: agents behave not like econometricians,

but like MSc theoreticians!

• Parameterised expectations algorithm to solve

the RBC model, eg den Haan and Marcet.

Learning: contribution to business

cycle/monetary policy analysis

• Cogley-Colacito-Sargent

– Model Fed as a Bayesian learning the weights to

put on competing models

– Includes model with long run trade-off

– Fed went for high inflation despite very low

chance that SS model was right because payoff in

event that it was right would be huge.

Learning: contributions/ctd

• Expectations/ learning can be an extra source

of propagation [explaining why cycles so large]

and origin of cycles: expectational shocks.

• Optimal policy with adaptive learning found to

be more hawkish. Stamping out persistence in

inflation stops expectations rising, so stops

inflation itself.

• BoC study of possible switch to price level

targeting. Didn’t go for it for reasons related

to learning.

Other non-rational expectations

models in the ‘wilderness’

• Sims: hyper-rational, ‘rational inattention’

– Watch things only if they r important and vary a

lot, to economise on time and costs

• Mankiw and Reis: ‘sticky information’

– Respond rationally, but have old information

• Brock and Hommes, King…Yates: ‘heuristicswitching.

– Switch amongst rules of thumb according to noisy

observation on performance of each

The heuristic-switching model

t E t

t x t e t

e t e t1 z t

T

T

x t a

,

0

t

T

1 : Et

t

1 0

2 : Et

t

1

t1

Simple NK model. Output gap is

instrument of cb. Persistent

shocks to give role for dynamic

forecasts. Zero inflation target.

Agents choose from two

heuristic forecasts of

inflation. The target, and

phi*lagged inflation

T

Et

1 n t

n t

t

1 n t

t1

t1

Epi is the weighted sum of e across different agents.

Determining % that use a heuristic

F it 1/h

n it

t

2

E

s

s

is

sth

exp

F it

I

exp

F it

i1

Rolling window evaluation of

forecasting performance for a

heuristic.

N is the probability an agent chooses

a heuristic, or, aggregated, the

proportion that use it.

Theta=‘intensity of choice’ or, equivalently, noise with which F is

observed.

n T

n

Think of the model as a transformation mapping

an initial n into a future n.

We can ask whether there is a fixed point, and

what it looks like.

A possible attracting point or rest point of the

model

Learning: what you need to be

able to do

• Find the REE of a simple model

• Verify that non-RE expectations functions

generate expectational errors that violate RE.

• Understand what properties of Eerrors violate

RE.

• Understand motivation for and contribution of

non-RE models in business cycle analysis,

providing examples, and comprehensible,

short accounts of them.

What you need to be able to

do/ctd…

• Execute test for e-stability in simple models.

• Understand and formulate least squares

learning version of NK and simpler models.

• Understand where estability condition in least

squares learning model comes from. You

don’t have to derive the estability test.

What you need to be able to

do/ctd…

• Read and digest some examples of empirical

papers on REH; analyses of learning in macro.

• Use the papers listed in the lecture, and their

bibliographies.