Objectives

7.1, 7.2 Inference for comparing means of two populations

Matched pairs t confidence interval

Matched pairs t hypothesis test

Two-sample t significance test

Two-sample t confidence interval

Robustness and general assumptions

Non-normal population distributions and small samples

Adapted from authors’ slides © 2012 W.H. Freeman and Company

Matched pairs inference procedures

Sometimes we want to compare treatments or conditions at the

individual level. These situations produce two samples that are not

independent – they are related to each other. The subjects of one

sample are identical to, or matched (paired) with, the subjects of the

other sample.

Example: Pre-test and post-test studies look at data collected on the

same subjects before and after some “treatment” is performed.

Example: Twin studies often try to sort out the influence of genetic

factors by comparing a variable between sets of twins.

Example: Using people matched for age, sex, and education in social

studies helps to cancel out the effects of these potentially relevant

variables.

Except for pre/post studies, subjects should be randomized – assigned

to the samples at random (within each pair), in observational studies.

For data from a matched pair design, we use the observed differences

Xdifference = (X1 − X2) to test the difference in the two population means.

The hypotheses can then be expressed as

H0: µdifference= 0 ; Ha: µdifference>0 (or <0, or ≠0)

Conceptually, this is not different from our earlier tests for the

mean of one population. There is just one mean, µdifference, to test.

Sweetening colas (revisited)

The sweetness loss due to storage was evaluated by 10 professional tasters

(comparing the sweetness before and after storage).

Taster

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Change in Sweetness

−2.0

−0.4

−0.7

−2.0

0.4

−2.2

1.3

−1.2

−1.1

−2.3

We wanted to test if storage results

in a loss of sweetness, thus:

H0: μchange = 0 versus Ha: μchange > 0.

Although we did not mention it explicitly before, this is a pre-/post-test design

and the variable is the difference: Sweetnessafter – Sweetnessbefore.

A matched pairs test of significance is therefore just like a one-sample test.

Does lack of caffeine increase depression?

Individuals diagnosed as caffeine-dependent were deprived of caffeine-rich

foods and assigned pills for 10 days. Sometimes, the pills contained caffeine

and other times they contained a placebo. A depression score was determined

separately for the caffeine pills (as a whole) and for the placebo pills.

There are 2 data points for each subject, but we only look at the difference.

We calculate that x diff = 7.36; sdiff = 6.92, df = 10.

We test H0: μdifference = 0, Ha: μdifference > 0,

using α = 0.05. Why is a one-sided test ok?

t

x diff 0

s diff

n

7.36

3.53.

6.92 / 11

From the t-distribution: P-value = .0027,

which is quite small, in fact smaller than α.

D e p re s s io n

D e p re s s io n

S u b je c t w ith C a ffe in e w ith P la c e b o

1

5

16

2

5

23

3

4

5

4

3

7

P la c e b o C a fe in e

11

18

1

4

5

6

8

5

14

24

6

19

7

8

9

10

11

0

0

2

11

1

6

3

15

12

0

6

3

13

1

-1

Depression is greater with the placebo than with the caffeine pills, on average.

The weight of calves

It is clear that the weight of a calf increases over time. However, it

may be a surprise to learn that the increase is not immediate. This

can be seen by analyzing the calf weight data that we have been

studying over the past few weeks.

Look at the calf data in Statcrunch, to see how much weight each of

the calves gain or loose in Week 1, it is clear that we must take the

difference between the weight at week 0 – weight at week 1, and the

analysis needs to be done on the differences (these can be stored in

your Statcrunch spreadsheet).

Now we conduct an identical analysis to the one-sample methods but

on the differences, we obtain the table below (these numbers were

obtained in statcrunch). Observe to obtain the t-transform we need

the mean difference and the standard error (which is a measure of

spread of the mean difference), the t-transform = (mean difference 0)/s.e.

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Average

3.78

difference

week 0-week n

5.53

-0.46

-8.33

Standard Error 0.58

0.49

0.69

0.97

t-transform

6.488

11.13

-0.66

-8.62

Ha: µdifference<0

No evidence

Average >0

No evidence

Average > 0

No evidence,

Yes,

pvalue = 0.256 pvalue<0.0001

Ha: µdifference=0

Yes,

Yes,

No evidence

pvalue<0.0001 pvalue<0.0001 pvalue=0.265

Yes,

pvalue<0.0001

Ha: µdifference>0

Yes,

Yes,

No evidence

pvalue<0.0001 pvalue<0.0001 Average < 0

No evidence,

Average <0

We see that from Week 1 to Week 2 there is a drop in weight, in fact the ttransform in Week 2 is much greater than the t-transform in Week 1, so the pvalue in Week 2 is a lot smaller than the p-value in Week 1. In Week 3, we do

not reject any hypothesis, this suggests that the weight is back to birth weight.

And from Week 4 onwards we see a gain in weight.

CI for the mean weight difference

Below we construct 95% CI (using t-dist 47 df, 2.5%) for the mean

difference. The mean difference is likely to be in this interval.

Week 1 CI

[3.78 ±2.01×0.58] = [2.61,4.96]

Week 2 CI

[5.53 ±2.01×0.49] =[4.45,6.51]

Week 3 CI

[-0.46 ±2.01×0.69]=[-1.81,0.92]

Week 4 CI

[-8.33 ±2.01×0.97]=[-10.28,-6.37]

Since zero does no lie in the the Intervals for Week 1, Week 2 and Week 4,

this means we are rejecting the null on the two sided test (at the 5% level),

and the p-value is less than 2.5%.

Using the information above we can 95% construct intervals for the weight of

a randomly selected healthy calf. This will be much wider than the intervals

above, and will not decrease with sample size. Such intervals can help us

determine whether a calf is healthy or not. How to construct such intervals is

beyond this course.

Independent samples inference

The purpose of most studies is to compare the effects of different

treatments or conditions. In fact, the most effective studies are the

ones that make direct comparisons from data within the studies.

Often the subjects are observed separately under the different

conditions, resulting in samples that are independent. That is, the

subjects of each sample are obtained and observed separately from,

and without any regard to, the subjects of the other samples.

Example: Students are randomly assigned to one of two classes.

Those in the first class are given iPads that they bring to class to be

interactively involved. The other class has a more traditional format.

Example: An economist obtains labor data from subjects in France and

from subjects in the U.S. The samples are independently obtained.

As in the matched pairs design, subjects should be randomized –

assigned to the samples at random, when the study is observational.

Independent sample scenarios

Subjects in the samples are obtained and observed separately, and

without any relationship to subjects in the other sample(s).

Population 1

Population 2

Sample 1

Sample 2

Sample 1 is randomly obtained from Population 1

and, by an independent (separate/unrelated) means,

Sample 2 is randomly obtained from Population 2.

Independence is not the

same as “different”.

Population

Sample 1 is randomly obtained and its subjects are

given Treatment 1, and independently Sample 2 is

randomly obtained from the same Population and its

subjects are given Treatment 2.

Sample 2

Sample 1

Difference of two sample means

We are interested in two populations/conditions with respective

parameters (μ1, σ1) and (μ2, σ2).

We obtain two independent simple random samples with respective

statistics (x1 , s1) and (x 2, s2).

We use x1 and x 2 to estimate the unknown μ1 and μ2.

We use s1 and s2 to estimate the unknown σ1 and σ2.

Since we wish to compare the means, we use x1 x 2 to estimate

the difference in means μ1 − μ2.

After the original coffee sales study, the marketing firm obtained independent

random samples: 34 “West Coast” shops and 29 “East Coast” shops. The firm

observed the average number of customers (per day) over 2 week periods.

The two sample means were xW C = 295 and x E C = 319.

Thus, they estimate that East Coast shops have an average of 319 − 295 = 24

customers more per day than West Coast shops do.

Distribution of the difference of means

In order to do statistical inference, we must know a few things

about the sampling distribution of our statistic.

The sampling distribution of x1 x 2 has standard deviation

2

1

n1

2

2

n2

.

(Mathematically, the variance of the difference is the sum of

the variances of the two sample means.)

This is estimated by the standard error (SE)

2

s1

n1

.

( x1 x 2 ) ( 1 2 )

2

s1

n1

n2

For sufficiently large samples, the distribution is approximately normal.

Then the two-sample t statistic is t

2

s2

.

2

s2

n2

This statistic has an approximate t-distribution on which we will base

our inferences. But the degrees of freedom is complicated …

Two sample degrees of freedom

Statisticians have a formula for estimating the proper degrees of freedom

(called the unpooled df). Most statistical software will do this and you

don’t need to learn it.

s 2 s 2

1

2

n

n

1

2

2

df

2

2

1 s1

1 s 2

n 1 1 n 1 n 2 1 n 2

2

2

df > smaller of (n1−1,n2−1), which can be used instead of the unpooled df.

This is called the conservative degrees of freedom. It is useful for doing

HW problems, but for practical problems you should use statistical

software which will use the more accurate unpooled df.

The strange standard error

2

s1

n1

2

s2

n2

.

The standard error for the two sample test looks

quite crazy. But it is quite logical. We recall that in

the one sample test the standard error decreased

as the sample size increased (this is because the

sample standard deviation stayed about the

same) but n grew, which meant that the standard

error decreased.

In the two sample case, now there are two sample sizes, both sample sizes must

increase in order that the standard error decreases. Consider the following

examples:

If the size of one sample stays the same, but the other decreases, the standard

error does not decrease much. This is because the estimator of one of the means

will not improve – consider the case that there is only one person in a group.

If the standard deviations of both populations are about the same, and overall

the number of subjects in a study is fixed, then using equal number of subjects in

each group leads to the smallest standard error.

Two-sample t significance test

The null hypothesis is that both population means μ1 and μ2 are equal,

thus their difference is equal to zero.

H0: μ1 = μ2 H0: μ1 − μ2 0 .

Either a one-sided or a two-sided alternative hypothesis can be tested.

Using the value (μ1 − μ2) 0 given in H0, the test statistic becomes

t

( x1 x 2 ) 0

2

s1

n1

.

2

s2

n2

To find the P-value, we look up the appropriate probability of the

t-distribution using either the unpooled df or, more

conservatively, df = smaller of (n1 − 1, n2 − 1).

Does smoking damage the lungs of children exposed to

parental smoking?

Forced vital capacity (FVC) is the volume (in milliliters) of air

that an individual can exhale in 6 seconds.

We want to know whether parental smoking decreases

children’s lung capacity as measured by the FVC test.

Is the mean FVC lower in the population of children

exposed to parental smoking than it is in children not

exposed?

FVC was obtained for a sample of children not

exposed to parental smoking and a group of

children exposed to parental smoking.

Parental smoking

FVC avg.

s

n

Yes

75.5

9.3

30

No

88.2

15.1

30

H0: μsmoke = μno ↔ H0: (μsmoke − μno) = 0

Ha: μsmoke < μno ↔ Ha: (μsmoke − μno) < 0 (one-sided)

The observed “effect” is

x sm oke x no 75.5 88.2 12.7,

a substantial reduction in FVC. But is it

“significant”?

To answer this, we calculate the tstatistic:

t

( x sm oke x no ) 0

2

s sm oke

n sm oke

2

s no

n no

75.5 88.2

2

9.3

30

15.1

30

2

Parental smoking

FVC avg.

s

n

Yes

75.5

9.3

30

No

88.2

15.1

30

12.7

2.883 7.600

3.922.

Even if we use df = smaller of (nsmoke−1, nno−1) = 29 we find that a t-statistic >

3.659 gives a P-value < 0.0005 (for a one sided test). So our t = −3.922 is

very significant. And so we reject H0.

Lung capacity is significantly impaired in children of smoking parents.

The influence of Betaine on weight

We want to investigate the effect that Betaine may have on the

weight of calves. In order to determine its influence, a comparison

needs to be made with a control group (calves not given Betaine).

To statistically test whether Betaine has an influence, we draw two

random samples, these form the two groups. In one group of calves

Betaine is given and their weight is recorded over 8 weeks in the

another group only milk is given and their weights recorded.

Our data set only contains 11 calves in each group, the sample

sizes are both very small, therefore if there is a difference between

the Betaine group and the control group, the difference must be

large for to be able to detect it (reject the null), this is because the

standard error for small samples will be quite large.

If you want to replicate our results, recall that TRT = B corresponds to the

group given Betaine and TRT = C the calves given only milk.

We will test that the mean difference in weights between those given Betaine

those not given Betaine is zero against the alternative that the mean difference is

different. We summarise the results below.

size

Sample Mean

mean

Diff.

St. dev

Group

Control

11

144.45

16.12

Group

Betaine

11

139.54

15.51

Difference

4.91

St. err

Ttransfo

rm

P-value

6.74

0.727

0.24

We observe that the t-transform is small and the p-value is large, thus we cannot

reject the null at the 10% level. This could be because there is no difference, or that

there is a difference but there is too much variability in the data for us to see a

significant difference with such small sample sizes.

Significant effect

Remember: Significance means the evidence of the data is sufficient to

reject the null hypothesis (at our stated level α). Only data, and the

statistics we calculate from the data, can be statistically “significant”.

We can say that the sample means are “significantly different” or that

the observed effect is “significant”. But the conclusion about the

population means is simply “they are different.”

The observed effect of −12.7 on FVC of smoking parents is significant

so we conclude that the true effect μsmoke − μno is less than zero.

Having made this conclusion, or even if we have not, we can always

estimate the difference using a confidence interval.

Two-sample t confidence interval

Recall that we have two independent samples and we use the

difference between the sample averages ( x1 x 2) to estimate (μ1 − μ2).

2

This estimate has standard error SE

n1

2

s2

.

n2

The margin of error for a confidence interval of μ1 − μ2 is

2

*

m t

s1

n1

s1

2

s2

*

t SE

n2

We find t* in the line of Table D for the unpooled df (or for the smaller of

(n1−1, n2−1)) and in the column for confidence level C.

The confidence interval is then computed as ( x1 x 2 ) m .

The interpretation of “confidence” is the same as before: it is the

proportion of possible samples for which the method leads to a true

statement about the parameters.

Obtain a 99% confidence interval for the smoking damage

done to lungs of children exposed to parental smoking, as

measured by forced vital capacity (FVC).

The observed “effect” is

x sm oke x no 75.5 88.2 12.7.

Using df = smaller of (nsmoke−1, nno−1)

= 29 we find t* = 2.756.

The margin of error is

*

mt

2

s sm oke

n sm oke

2

s no

n no

Parental smoking

FVC avg.

s

n

Yes

75.5

9.3

30

No

88.2

15.1

30

2.756

2

9.3

30

15.1

30

2

8.92.

And the 99% confidence interval is

( x sm oke x no ) m 12.7 8.92 ( 21.62, 3.78).

We conclude that the FVC of lung capacity is diminished on average by a

value between 3.78 and 21.62 in children of smoking parents, with 99%

confidence.

Can directed reading activities in the classroom help improve reading ability?

A class of 21 third-graders participates in these activities for 8 weeks while a

control classroom of 23 third-graders follows the same curriculum without the

activities. After 8 weeks, all children take a reading test (scores below).

95% confidence interval for (μ1 − µ2), with df = 20 conservatively t* = 2.086.

2

*

C I : ( x1 x 2 ) m ; m t

s1

n1

2

s2

2.086 4.308 8.99.

n2

With 95% confidence, (µ1 − µ2) falls within 9.96 ± 8.99 or 0.97 to 18.95.

95% confidence interval for the reading ability study using the more precise

degrees of freedom.

If you round the df, round down, in this case

to 37. So t* = 2.025 (interpolating the table).

2

*

mt

s1

n1

2

s2

n2

m 2.025 4.308 8.72

C I : 9.96 8.72 (1.24,18.68)

Note that this method gives a smaller margin

of error, so it is to our advantage to use the

more precise degrees of freedom.

From StatCrunch: [Stat-T Statistics-Two Sample,

uncheck “pool variances”]

Summary for testing μ1 = μ2 with independent

samples

The hypotheses are identified before collecting/observing data.

To test the null hypothesis H0: μ1 = μ2, use t x1 x 2 .

2

s1

n1

2

s2

n2

The P-value is obtained from the t-distribution (or t-table) with the

unpooled degrees of freedom (computed).

For a one-sided test with Ha: μ1 < μ2, P-value = area to left of t.

For a one-sided test with Ha: μ1 > μ2, P-value = area to right of t.

For a two-sided test with Ha: μ1 μ2, P-value = smaller of the above.

If P-value < α then H0 is rejected and Ha is accepted (one sided – if

two-sided then P-value < α/2). Otherwise, H0 is not rejected even if

the evidence is on the same side as the alternative Ha.

Report the P-value as well as your conclusion.

You must decide what α you will use before the study or else it is

meaningless.

Summary for estimating μ1 − μ2 with independent

samples

The single value estimate is x1 x 2 .

2

s1

2

s2

This has standard error

The margin of error for an interval with confidence level C is

*

m t

2

s1

n1

n1

n2

.

2

s2

n2

,

where t* is from the t-distribution using the unpooled degrees of

freedom.

The confidence interval is then ( x1 x 2 ) m .

You must decide what C you will use before the study or else it is

meaningless.

For both hypothesis tests and confidence intervals, the key is to

use the correct standard error and degrees of freedom for the

problem (what is being estimated and how the data are obtained).

Coffee Shop Customers: West Coast vs. East Coast

The marketing firm obtained two independent random samples: 34 “West

Coast” coffee shops and 29 “East Coast” coffee shops. For each shop, the

firm observed the average number of customers (per day) over 2 week

periods.

Here μWC is the mean, for all West Coast coffee shops, of the variable XWC =

“daily average number of customers”. Likewise, μEC is the corresponding

mean for all East Coast coffee shops.

Side-by-side boxplots help us compare

the two samples visually.

The West Coast values are generally

lower and have slightly more spread

than the East Coast values.

Coffee Shop Customers (cont.)

Is there a difference in the daily average number of customers

between West Coast shops and East Coast shops?

Test the hypotheses H0: μWC = μEC vs. Ha: μWC μEC.

We will use significance level α = 0.01.

From StatCrunch, the P-value = 0.0028 < 0.01, so H0 is rejected.

Coffee Shop Customers (cont.)

Find the 98% confidence interval for μWC − μEC.

The confidence interval can be used to conduct a two-sided test

with significance level α = 1 − C.

Since the confidence interval does not contain 0, we can reject the null

hypothesis that μWC = μEC.

Using this method to conduct a test, however, does not provide a Pvalue. Knowing the P-value is important so that you know the strength

of your evidence, and not just whether it rejects H0.

It is possible to modify this method in order to conduct a one-sided test

instead. (Use C = 1 − 2α and reject H0 only if the data agree with Ha.)

Pooled two-sample procedures

There are two versions of the two-sample t-test: one assuming equal

variances (“pooled 2-sample test”) and one not assuming equal

variances (“unpooled 2-sample test”) for the two populations. They

have slightly different formulas and degrees of freedom.

The pooled (equal variance) twosample t-test is mathematically exact.

However, the assumption of equal

variance is hard to check, and thus

the unpooled (unequal variance) ttest is safer.

Two normally distributed populations

with unequal variances

In fact, the two tests give very similar

results when the sample variances

are not very different.

When both population have the

same standard deviation σ, the

pooled estimator of σ2 is:

2

2

sp

2

(n 1 1)s1 ( n 2 1) s 2

(n1 n 2 2)

sp replaces s1 and s2 in the standard error computation. The sampling

distribution for the t-statistic

is the t distribution with (n1 + n2 − 2)

degrees of freedom.

2

A level C confidence interval for µ1 − µ2 is

x1 x 2 ) t *

sp

2

n1

sp

n2

(with area C between −t* and t*)

t

x1 x 2

2

sp

n1

2

sp

n2

To test the hypothesis H0: µ1 = µ2 against a

one-sided or a two-sided alternative, compute

the pooled two-sample t statistic for the

t(n1 + n2 − 2) distribution.

Which type of test? One sample, paired samples or two

independent samples?

Comparing vitamin content of bread

Is blood pressure altered by use of

immediately after baking vs. 3 days

an oral contraceptive? Comparing

later (the same loaves are used on

a group of women not using an

day one and 3 days later).

oral contraceptive with a group

taking it.

Comparing vitamin content of bread

immediately after baking vs. 3 days

Review insurance records for

later (tests made on independent

dollar amount paid after fire

loaves).

damage in houses equipped with a

fire extinguisher vs. houses

Average fuel efficiency for 2005

vehicles is 21 miles per gallon. Is

average fuel efficiency higher in the

new generation “green vehicles”?

without one. Was there a

difference in the average dollar

amount paid?

Cautions about the two sample t-test or interval

Using the correct standard error and degrees of freedom is critical.

As in the one sample t-test, the method assumes simple random

samples.

Likewise, it also assumes the populations have normal distributions.

Skewness and outliers can make the methods inaccurate (that is, having

confidence/significance level other that what they are supposed to have).

The larger the sample sizes, the less this is a problem.

It also is less of a problem if the populations have similar skewness and

the two samples are close to the same size.

“Significant effect” merely means we have sufficient evidence to say

the two true means are different. It does not explain why they are

different or how meaningful/important the difference is.

A confidence interval is needed to determine how big the effect is.

Hazards with skewness

To see how skewness affects statistical inference, we can do some

simulations.

We use data from the “exponential” distribution, which is highly skewed.

In StatCrunch: [Data-Simulate-Exponential, enter mean value = 1]

Hazards with skewness, cont.

We now simulate 1000 samples of size n = 25 and compute the tstatistic for each sample.

In StatCrunch: [Data-Simulate-Exponential, enter 25 rows, 1000 columns, mean

value = 1, and statistic sqrt(25)*(mean(Exponential)-1)/std(Exponential)]

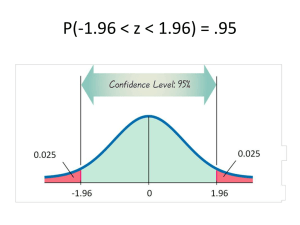

With df = 24, we find

t* = 2.064 for C = 95% and

t* = 2.492 for C = 98%.

But the corresponding

percentiles of the actual

sampling distribution are

wildly different.

Only 93.5% of CI’s

computed with C = 95% will

contain the true mean.