Dionysus - WordPress.com

advertisement

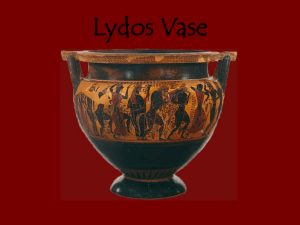

Dionysus God of Wine , Music & ecstasy . Birth of Dionysus Dionysus is the only god to have a human mother. Semele was the daughter of Cadmus, king of Thebes. Zeus sewed the embryo into his thigh and birthed it himself. Seduced by Zeus, she inspired Hera’s jealousy. Hera tricked her into asking Zeus to show himself to her in his true form. Exposed to divine reality, she was burned up. Only the glowing embryo of Dionysus remained. Birth of Dionysus As Athena’s birth from Zeus’s head signifies her intellect and purity, Dionysus’ birth from Zeus’s thigh associates him with physical sensation and chaotic sexuality. Also a little bit of gender bending. Dionysus was raised by various nymphs and other woodland creatures. Here Hermes brings him to Silenus, the old, forest-living, wine-loving satyr often shown in the god’s retinue. Appearance of Dionysus Dionysus may be shown as a bearded older man . . . . . . or as a sensual, even effeminate, beardless youth. Flexible age image, as with Hermes. The Nature of Dionysus This dual nature, especially the effeminate aspect, was a little scary. The wild, effeminate portrayal of Dionysus emphasizes the threat of ecstatic experience to what is dignified and proper. Greek mythology emphasized the foreign, Eastern origins of Dionysus, but archeological evidence suggests he is as old as the other Greek gods. “The East” was a symbol of decadence and extremes. The Nature of Dionysus On the other hand, the Greeks regarded a little drunken partying as a good thing. In the Anthesteria, a 3-day Athenian festival, much of the second day was devoted to wine tasting and drinking contests, open to all men above the age of three, slave and free alike. Dionysus matched Demeter’s gift of grain, with wine. He turned the grapes into a flowing drink and offered it to mortals, so when they fill themselves with the liquid vine, they put an end to grief. Euripides, Bacchae The Nature of Dionysus Dionysus was the god of drama, which embodied aspects of ecstasy (“standing outside oneself”): the actors impersonated mythological characters, and the audience experienced feelings and emotions incited by the plays. catharsis, or emotional release, is one of the things Dionysus offers. The Nature of Dionysus But drama was also a civic, community thing. Major civic festivals, such as the dramatic festivals of Lenaia and Dionysia, as well as the more “sober” parts of the Anthesteria, emphasized Dionysus’ role as a god whose power supported a well balanced life, both family and civic. Dionysus & the Pirates First of all a sweet and fragrant wine flowed through the black ship, and a divine ambrosial odor arose . . . immediately a vine spread in all directions from the top of the sail, with many clusters hanging down . . . the sailors escaped an evil fate and leaped into the shining sea and became dolphins. Homeric Hymn to Dionysus Dionysus & his retinue Dionysus is thought of as accompanied by not-quite-human satyrs (half-man, halfgoat). Satyrs are another symbol of the mysterious powers of nature and the wild. Satyrs are a little bit crazy, often oversexed, fond of wine. Pan is the quintessential satyr. Dionysus & his retinue Satyrs and nymphs accompany the god. The satyrs play musical instruments and the nymphs are shown dancing with krotala (castanets). Attributes: •wine cup •music & dance •nymphs & satyrs •trailing ivy Music and dance are essential to Dionysiac celebration. Dionysus & his retinue Maenads are a key feature of Dionysus’ retinue. Attributes: •fawn skin or panther skin (dappled, “camouflage”) •thyrsus (pinecone or ivy-tipped rod, kinda phallic) •mastery over & connection •wild, ecstatic with wild dancing, head animals turned up or back Ariadne Dionysus married Ariadne, the daughter of the king of Crete, when he found her sleeping on Naxos Euripides’ Bacchae Major characters: Dionsysus: The god is disguised as his own priest. Pentheus: The young king of Thebes. He wants to run his city in a strict, orderly fashion. Euripides wrote the Bacchae at the end of his life. It is one of his most masterful plays and shows the tension between the drive to live a normal, controlled life, and the divine power of chaos that Dionysus brings. Bacchae: the chorus, a group of women who followed their god from Asia, sleeping in the woods, dancing, and hunting. Euripides’ Bacchae Cadmus, the oldking of Thebes (Pentheus’ & Dionysus’ grandfather) Tiresias, the old blind seer: two old men who, ridiculous though it is, have recognized the god’s power and are dancing in celebration of him. Chorus: What is wisdom? What is beauty? Slowly but surely the divine power moves to annul the brutally minded man who in his wild delusions refuses to reverence the gods. . . Euripides, Bacchae Euripides’ Bacchae It’s a foregone conclusion: Pentheus cannot fight the power of the god; brainwashed and driven insane, he participates in his own sparagmos . . . The innocent suffer too, as his mother and grandfather are bereaved, despite accepting the god. •What principles fuel the conflict between Pentheus and Dionysus? •Are these inevitable conflicts of the human soul? •What is wisdom, according to the Dionysiac perspective? •Maenads’ speech p. 277 ff – what is happiness? What are the driving forces of their lives? •How do Tiresias and Cadmus feel about Dionysus? What are their reasons for following him despite the fact that it makes them ridiculous? •What views about morality and how to enforce it, arise in the conversation of Dionysus and Pentheus on p. 281-2? •What does the end of the play, with the destruction of Pentheus, say about the nature of Dionysus in specific, and the gods in general? So hail to you, Dionysus, rich in grape clusters; grant that we may in our joy go through these seasons again and again for many years. Homeric Hymn to Dionysus Dionysian Dionysian is a philosophical and literary concept, or dichotomy, based on certain features of ancient Greek mythology. Several Western philosophical and literary figures have invoked this dichotomy in critical and creative works, including Plutarch, Friedrich Nietzsche, Carl Jung, Franz Kafka, Robert A. Heinlein, Ruth Benedict, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, singers Jim Morrison and Iggy Pop, literary critic G. Wilson Knight, Ayn Rand, Stephen King, Michael Pollan, Diane Wakoski, Umberto Eco and cultural critic Camille Paglia. In Greek mythology, Apollo and Dionysus are both sons of Zeus. Apollo is the god of the Sun, dreams, reason, and plastic visual arts while Dionysus is the god of wine, music, ecstasy, and intoxication. In the modern literary usage of the concept, the contrast between Apollo and Dionysus symbolizes principles of collectivism versus individualism, light versus darkness, or civilization versus primitivism. The ancient Greeks did not consider the two gods to be opposites or rivals. However, Parnassus, the mythical home of poetry and all art, was strongly associated with each of the two gods in separate legends. German philosophy Although the use of the concepts of Apollonian and Dionysian is famously related to Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy, the terms were used before him in Prussia.[1] The poet Hölderlin used it, while Winckelmann talked of Bacchus, the god of wine. Nietzsche's usage Nietzsche's aesthetic usage of the concepts, which was later developed philosophically, was first developed in his book The Birth of Tragedy, which he published in 1872. His major premise here was that the fusion of Dionysian and Apollonian "Kunsttrieben" ("artistic impulses") forms dramatic arts, or tragedies. He goes on to argue that that has not been achieved since the ancient Greek tragedians. Nietzsche is adamant that the works of above all Aeschylus, and also Sophocles, represent the apex of artistic creation, the true realization of tragedy; it is with Euripides, he states, that tragedy begins its "Untergang" (literally "going under", meaning decline, deterioration, downfall, death, etc.). Nietzsche objects to Euripides' use of Socratic rationalism in his tragedies, claiming that the infusion of ethics and reason robs tragedy of its foundation, namely the fragile balance of the Dionysian. Nietzsche claimed in The Birth of Tragedy, in the interplay of Greek Tragedy: the tragic hero of the drama, the main protagonist, struggles to make order (in the Apollonian sense) of his unjust and chaotic (Dionysian) Fate, though he dies unfulfilled in the end. For the audience of such a drama, Nietzsche claimed, this tragedy allows us to sense an underlying essence, what he called the "Primordial Unity", which revives our Dionysian nature - which is almost indescribably pleasurable. Though he later dropped this concept saying it was “...burdened with all the errors of youth” (Attempt at Self Criticism, §2), the overarching theme was a sort of metaphysical solace or connection to the heart of creation, so to speak. Different from Kant's idea of the sublime, the Dionysian is all-inclusive rather than alienating to the viewer as a sublimating experience. The sublime needs critical distance, whereas the Dionysian demands a closeness of experience. According to Nietzsche, the critical distance, which separates man from his closest emotions, originates in Apollonian ideals, which in turn separate him from his essential connection with self. The Dionysian embraces the chaotic nature of such experience as all-important; not just on its own, but as it is intimately connected with the Apollonian. The Dionysian magnifies man, but only so far as he realizes that he is one and the same with all ordered human experience. The godlike unity of the Dionysian experience is of utmost importance in viewing the Dionysian as it is related to the Apollonian because it emphasizes the harmony that can be found within one’s chaotic experiences. Post-modern reading Nietzsche's idea has been interpreted as an expression of fragmented consciousness or existential instability by a variety of modern and post-modern writers, especially Martin Heidegger in Nietzsche and the Post-modernists. According to Peter Sloterdijk, the Dionysian and the Apollonian form a dialectic; they are contrasting, but Nietzsche does not mean one to be valued more than the other. Truth being primordial pain, our existential being is determined by the Dionysian/Apollonian dialectic. Extending the use of the Apollonian and Dionysian onto an argument on interaction between the mind and physical environment, Abraham Akkerman has pointed to masculine and feminine features of city form. نیچه یکی از نمونه های عالی خرمندی بینای دیونوسوسی را در حافظ می یابد.نام حافظ ده بار در مجموعه ی آثار وی آمده است.در نوشته های نیچه حافظ را به عنوان قله ی خردمندی شادمانی انسانی می ستاید.حافظ نزد او نماینده ی آن آزاده جانی شرقی ست که با وجد دیونوسوسی،با نگاهی تراژیک،زندگی را با شور سرشار می ستاید،به ّلذت های آن روی می کند و ،در همان حال به خطرها و بالهای آن پشت نمی کند .این ها ،از دید نیچه،ویژگی های رویکرد مثبت و دلیرانه،با رویکرد"تراژیک" به زندگی ست به حافظ،پرسش یک آبنوش" "' An Hafis. Frage eines "Wassertrinkers بهر خویش بنا کرده ای آن می خانه ای که تو از ِ گنجاتر از هر خانه ای ست، می ای که تو در آن پرورده ای همه-عالم آن را َسر کشیدن نتواند. آن پرنده ای که[نام اش] روزگاری ققنوس بود، میهمان توست، در خانه ِ آن موش که کوه زاد، همان -خود تو ای! همه و هیچ تو ای،می و می خانه تو ای، ققنوس تو ای،موش تو ای،کوه تو ای، که هماره در خود فرومی ریزی و هماره از خود َپر می کشی- فرورفتگی بلندی ها تو ای، ژرف ترین ِ روشنی ژرفناها تو ای، روشن ترین ِ مستی مستانه ترین مستی ها تو ای ِ -تو را ،تو را-با شراب چه کار؟ Pegah Khalesi