scholasticism

advertisement

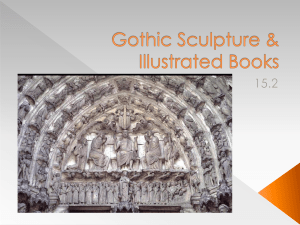

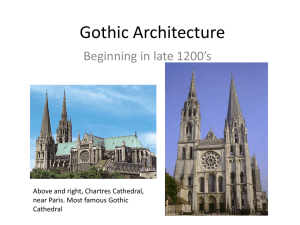

Gothic Structure in Relation to Aesthetics Mysticism and Logic In his book Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, Erwin Panofsky makes a detailed and convincing case for the cultural resonance between the formal characteristics of Gothic architecture and the culture of Scholasticism. Exemplified in the work of medieval scholars at such institutions as the School of Chartres and the University of Paris, Scholasticism was a system of organizing knowledge and building arguments through logical arrangement. Any question, problem or issue could be subdivided into numerous elements, all of which could fit neatly and logically into a larger superstructure called a summa. This system of arrangement was used to clarify difficult philosophical and theological questions, even in debates about the existence or non-existence of God. For this reason, scholasticism may at first seem to be unnecessarily complex and remote. Yet, it is, in fact, the basis of the way we organize information in an outline, an encyclopedia or the way we use binary mathematics in computer science. The great Summa Theologicae of St. Thomas Aquinas or the treatise Sic et Non [Yes and No] of Peter Abelard may be thought of as distant ancestors of contemporary digital theory. Erwin Panofsky’s interpretation of Gothic architecture rests on the proposition that Scholasticism was not just a rarefied concept practiced in the medieval academies but without popular relevance. He argues that direct as well as indirect exposure to the methods and processes of scholasticism made it a part of the common culture. The patronage of architects by the chapters of metropolitan cathedrals, the education of those who later became architects in schools sponsored by the church, public debates, and the sermons they heard would have helped bring the culture of scholasticism into the consciousness of the architects as a “mental habit.” By analogy, most people in our society, Panofsky observed, are trained neither in psychoanalysis nor in space technology, but we all use the terminology of these disciplines in our daily language. The increasingly rich life of professionalism in urban centers brought contact between various professions and elevated the competition among members of these groups. Architects were more urbane at this time. They were no longer usually monks; they were well read, and quite widely traveled. They enjoyed much more prestige than had their predecessors. The important point to keep in mind is that Panofsky does not claim that Gothic architects were trained in scholasticism, nor that they understood scholastic method as academicians did. Rather, he argues that scholasticism imbued high medieval society with a particular way of thinking and understanding that architects, as active participants in that society, could not escape. Therefore, the arguments he advances must be examined as claims for the architectural manifestation of a cultural phenomenon during the Gothic period. The fundamental principles of scholasticism are manifestatio and concordantia. Manifestatio means the elucidation or clarification of a subject in its totality. The result of this is the Summa, the vehicle for presentation. The three requirements of manifestatio are: (1) totality (completeness, thoroughness) (2) arrangement in a logical system of parts and sub-division of parts in sufficient articulation (3) distinctness and deductive cogency, ie. sufficient interrelation Concordantia is the acceptance and ultimate reconciliation of contradictory possibilities An easy way to imagine the scholastic method is to think about the organization of a book into chapters, sections, and sub-sections or the organization of an outline into divisions of Roman numerals, capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lower case letters. Book Chapter I Chapter II Section A. Section B. Section C. Sub-section 1. Sub-section 2. I. A. B. 1. 2. 3. a. b. II. The tendency in this system is to move toward an obsession with systematic divisions, sub-divisions, methodical demonstrations, and the appearance of artificial symmetries to make sure that the visual vehicle appropriately expresses the method that creates it. According to Panofsky’s reasoning, the “mental habit” of scholasticism naturally finds its way into other works; and it is particularly visible in the development of the High Gothic cathedrals in the Ile-de-France. Their structural principles were revealed not only in the functioning structural elements but in the way in which the structural elements were arranged visually, even when they do not actually serve a structural function. The High Gothic equivalent of scholastic manifestatio is the “principle of transparency.” What you see on the outside is directly related to and is driven by the expression on the inside. The interior of the High Gothic cathedral is a delimited volume separated from the exterior space but projects itself through the surrounding structure. Next images: Cathedral of Notre Dame at Chartres Next images: Cathedral of Notre-Dame at Reims Next images: Cathedral of Notre Dame at Amiens The unified whole must consist of identifiable and separate parts. We must be able to infer the interior from the exterior and the organization of the whole system from the cross-section of one pier. Visual logic is a part of manifestatio. Not everything that we see in the elevation of the interior really works; but it represents the larger scheme of parts which do work. Next images: nave elevations of Chartres and Reims Next images: nave elevations at Reims and Amiens Next images: nave and choir elevations at Amiens Next images: Chartres and Reims Next images: Reims and Amiens Erwin Panofsky’s assessment of the relationship between faith and reason in the high middle ages is that within the parameters of mysticism, reason was drowned in faith. Later, Nominalism would separate reason and faith altogether. But during the 12th century, reason was used as a means of laying out faith within the scholastic system while mysticism became a source of faith. This complex and layered relationship is made visible to an extent within the high Gothic cathedral, especially as the repository for stained glass that filled the interiors with a mystical chromatic light. The illumination of the environment is one of its most overwhelming experiences. The colored light can seem to dissolve the very stone structure itself. Cathedral of St. Etienne at Bourges