human races - Language Log

advertisement

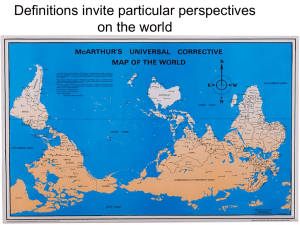

The Reality of Race I There are consistent differences between different human populations. If you placed 100 San Bushman (from Southern Africa) in a room with 100 native Japanese, and with 100 native Swedes and with 100 native Australians, all of you could sort out the members of each of these populations with 100% accuracy. However, if you placed 100 Egyptians in another room with 100 Sudanese, with 100 Turkish people, with 100 Jordanians , it would be extremely difficult to sort out these people. Human variation I Human Variation II The Reality of Race II People are distinct across broad geographic ranges (for example, between the populations from the Kalahari and from Sweden). However, humans are continuously distributed, with no distinct borders or boundaries separating populations. Biological features gradually change from one geographic area to another. Thus, there is both a reality of human difference between peoples from distant locales, and at the same time, no reality to the concept of racial groups bounded by distinct borders. Thus: can races be defined? If there are no distinctive features that provide boundaries between human populations, then why have the traditional views of race as distinctive groups developed? And do most people believe that there is a reality to human races as separate entities? Much of this is the result of the history of the study of human biology and variation. Up until the latter part of the 20th century, races were viewed as groups with fixed and identifiable borders. Various authors defined the number of races and their distributions in numerous ways. Five Races History of the Concept of Race Humans have used the concept of race for centuries as a way of elevating the image of their own group. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there was great debate about the nature of human difference. In the U.S., much of this debate focused on the practice of slavery and whether the Declaration of Independence ‘s reference to the ideal that “all men are created equal...” also referred to African American slaves. Jefferson and the Declaration About two miles from where we are today, Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, a document that, perhaps more than any other, established the central concept of the U.S. Jefferson wrote, as we have seen, that it was a “self evident” truth “that all men are created equal”. For Jefferson, this meant precisely that all humans, with their different physical features, were part of the same creation? And thus to be considered in the same fashion, legally, socially and politically? This was the background for the debates surrounding both the meaning and utility of a concept of race as well as the justifications for slavery. The U.S. and Race What made this debate even more meaningful in the U.S. was that here, unlike late 18th century Europe, where peoples were relatively similar in appearance, and it was unusual to meet an individual with exotic features. In the U.S., this was a normal pattern with Native Americans, and individuals of African and European background routinely passing each other on the street. Further, the unequal distribution of property and civil rights between the various groups and the bias in the law toward Europeans (and northwest Europeans in particular) also played a role in focusing attention on the differences that distinguished humans. Race as an Issue in the U.S. Thus after the revolution, the United States became heavily involved with the concept of race especially as it impacted on the larger issue of slavery. Great Britain outlawed slavery in the Empire in 1807, and from this time on, there were periodic conflicts with the U.S. when Royal Navy ships, patrolling the west coast of Africa, would intercept American slave ships. Race in early 19th Century Britain This did not, of course, end the idea in Britain of differences between races. In 1799, surgeon Charles White recounted his belief that despite the ability of all humans to successfully interbreed, we did not constitute a single species, nor was the environment a factor in the emergence of physical differences. His views, like many others before and after, were inextricably tied to the high value they placed on the nobility of his own kind. For White, the white European, the Caucasian, the Aryan, the Teuton, possessed truly wonderous gifts: “none would doubt the white European’s intellectual magnificence, surely superior to that of every other man”. Where else shall we find, he asked: Race and Beauty “That nobly arched head, containing such a quantity of brain….? Where that variety of features, and fullness of expression, those long, flowing, graceful ring-lets; that majestic beard, those rosy cheeks and coral lips? Where that….noble gait? In what other quarter of the globe shall we find the blush that overspreads the soft features of the beautiful women of Europe, that emblem of modesty, of delicate feelings…? Where, except on the bosom of the European woman, two such plump and snowy hemispheres, tipt with vermilion?” Charles White, English physician (1799) Philadelphia in the early 19th C. Philadelphia, as a Quaker city, was a center for abolitionist activity in the years before the Civil War (remember, this was a time before the publication of The Origin of Species) One leader, Samuel Stanhope Smith, Professor of Natural Theology at the College of New Jersey (later to become Princeton) actually argued that differences in the appearance of Europeans and Africans was due entirely to environmental influence, including their status in society, and that if a African’s lot improved, they would begin to look more like Europeans. Phrenology Samuel Morton (1799-1851) Considered by some as the founder of American physical anthropology, Morton was a physician whose views on human variation would have a deep and long lived influence on the study of human variation and its meaning. Morton used the collection of human skulls that he had amassed (more than 1200 at his death) from virtually every human population on the planet to examine the nature of human variation in cranial structures. Morton’s racial ideas Amongst Morton’s skull collection were a number recovered from ancient Egyptian cemeteries and when he compared these with modern Egyptians, Morton concluded that there was virtually no differences in the skulls. There were, he argued, significant differences in the skulls of living Europeans when compared with those of Africans. In Morton’s time the ancient Egyptians were considered to be from remotest antiquity, near to the beginnings of human existence. If there was no difference between the two Egyptian groups, but much differences between Europeans and Africans, then the differences between racial groups were as old as the groups themselves. Americana book The Influence of Morton’s Racial Views Thus, Morton concluded that what were considered the races of humans were actually different species whose differences went back to human origins. Because Morton used what were, for the time, extremely scientific methods, his work was accepted in many scientific circles here and in Europe. After Morton’s death, two others, amateur Egyptologist George Glidden and an Alabama physician, Josiah Nott widely communicated Morton’s views to scientific audiences in the U.S. and abroad. In the years prior to the Civil War, Morton’s work was employed by many, included those in Congress, as a justification for the maintenance of slavery. Morton Egypt Morton skull Morton race Early 19th Century Studies Thus, prior to the publication of The Origin of Species (1859), most studies of race focused on the identification of distinct racial groups, and the specific biological traits of each group. At this time, there was little appreciation of the nature and importance of variation, and there was a general view that races were originally composed of people who all looked exactly alike. This was the origin of the concept of the ‘Pure Race”. “For nearly two centuries anthropologists have been directing their attention principally toward the task of establishing criteria by whose means races of mankind might be defined. All have taken completely for granted the one thing which required to be proved, namely that the concept of race corresponded with a reality which could actually be measured and verified and descriptively set out so that it could be seen to be a fact. In short, that the anthropological conception of race is true which states that there exists in nature groups of human beings comprised of individuals each of whom possesses a certain aggregate of characters which individually and collectively serve to distinguish them from individuals in other groups.” Ashley Montagu (1964:5) Color Chart Hair form Cephalic noses Race and Colonialism During the whole of the 19th Century, there were conflicts in most European countries between those who wished to totally exploit colonial peoples for economic gain, and those who fought for a more enlightened approach. One unintended consequence of Darwin’s work was the employment of the concept of Natural Selection (“the survival of the fittest”) as a mechanism that also applied to the competition between societies. So-called “Social Darwinism” argued that since the European states were virtually always able to subdue non-Western peoples, t they were the most fit, and by implication their people were also the most fit. Later 19th Century Studies Although Darwin had emphasized the crucial importance of variation in the process of evolution, most studies of human races in the latter half of the 19th Century continued to stress stereotypes and fixed patterns in the work. In the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, and the unification of Germany, there arose in the 1870s a strong current of German nationalism. This was manifested in numerous ways including the retelling of German (or Teuton) origin myths, especially in the work of Richard Wagner and the Ring Cycle, but also in the work of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and his views of the untermensch and ubermensch. Nationalism and Race In addition to this work, other writers were also setting out origin stories and myths as representative of the early history of European peoples, especially those of northwest Europe. One of the earliest was the the Comte Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau, who in 1853 wrote a celebrated essay entitled: “On the inequality of the human races” Later, at the beginning of the 20th Century, a British writer Houston Chamberlin, wrote Foundations of the 19th Century. In both these works, the arguments, based on linguistics, archaeology and social philosophy, was that overwhelming evidence documents that the northwest Europeans, the socalled Nordics, Teutons or Aryans, were the race that was responsible for most of the great achievements of western humankind, and that they should deserve to be masters of other, less well endowed groups. “Pure Races” Through much of the 19th Century, pure races were thought to have characterized the early development of our species. Later on, as these pure racial groups met and mixed with other such races, they interbred and became mixed. Original races were composed of individuals who all looked and behaved in the same way. This concept of race led to the ascribing of stereotypical notions about each race, especially having to do with behavior and intelligence. Madison Grant: The Passing of the Great Race (1916) Madison Grant, New York lawyer, writer, member of the board of the Bronx Zoo and the American Museum of Natural History, wrote a book that would have enormous implications for the population history in the U.S. In the this book, Grant argued that discoveries in archaeology, linguistics and genetics all showed that the Nordic race, having begun its existence in the mountains of southern Russia, migrated from there to their present locale in northwest Europe. These people possessed superior physical, psychological and neurological abilities and were able to subdue inferior peoples in their way. The Influence of the Aryan Peoples According to Grant, it was this group, with their superior intellect and general prowess, having passed through Palestine, Greece and Rome, were responsible for Christ, and Greek and Roman civilizations. After settling in northwest Europe, they were the driving force of the developments in Europe and were the major early settlers into America. It was there work and genius that resulted in the great American Republic. Grant argued that with the enormous influx of immigrants into the U.S., the quality of the genetic materials of the Nordics is being diluted and the U.S. faces an inevitable decline in greatness. The Immigration Act of 1921 The arguments made by Grant were used in Congress to pass the Johnson Immigration Act of 1921, which effectively ended the great age of European immigration into the U.S. This restrictive act set very low levels of immigration from all areas of the world into the U.S., with the exception of those people from northwest Europe whose immigration numbers were without limits. Pure Races and Biology The idea of pure races originated in the 19th century, before our understanding of basic biological mechanisms had developed. The concept of pure races implies that every individual in a population possesses the same alleles for every gene. Not only does this deny the continual introduction of mutations, but even if, by severe artificial breeding, a pure group were to be created, every individual would be effected by the same germs. A pathogen lethal to one would be lethal to all. Pure Races and Nazism The Nazis picked up many of the ideas that had begin to develop in the late 19th Century, and made them government policy. This resulted in one of the most unspeakable governmentally sanctioned mass murders in all history. The concept of the ‘pure race’ was at the core of the Nazi vision of a pure Nordic race, originally composed of individuals who were all tall, blond haired and blue eyed. The Nordics later came into contact with ‘inferior’ races, with intermixture diluting Nordic superiority The Nazis murdered millions of people who they believed were members of inferior races. This vision was applied not only to Jews but also to Eastern Europeans, Gypsies, Africans and South Asians and most East Asians except the Japanese. Responses to Nazi Racial Views Even before World War II, European scientists had responded strongly to the unscientific doctrines of Nazi racial ideas. For example, in 1936, two eminent British biologists, Julian Huxley and A.C. Haddon, had written a book, We Europeans, which showed in a clear, concise fashion the major errors in these views. In one famous observation in this book, the authors note that; “Our German neighbours have ascribed to themselves a Teutonic type that is fair, long-headed, tall and virile. Let us make a composite picture of a typical Teuton from the most prominent of the exponents of this view. Let him be as blond as Hitler, as dolicocephic as Rosenberg, as tall as Goebbels, as slender as Goering and as manly as Streicher. How much would he resemble the German ideal?”. The Aftermath: The UNESCO Statement on Race Since the end of WWII, UNESCO has issued a number of such Statements on Race: The first states, in part: “Racial doctrine is the outcome of a fundamentally anti-rational system of thought and is in glaring conflict with the whole humanist tradition of our civilization. Race hatred and conflict thrive on scientifically false ideas and are nourished by ignorance. Scientists have reached general agreement in recognizing that mankind is one: that all men belong to the same species. UNESCO Statement II From the biological standpoint, the species Homo sapiens is made up of a number of populations, each one of which differs from the others in the frequency of one or more genes. National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups. With respect to reace-mixture, the evidence points unequivocally to the fact that this has been goingon from the earliest times. The biological fact of race and the myth of ‘race’ should be distinguished. The 1960s: Evolution & Variation “From Whatever viewpoint one approaches the question of the applicability of the concept of race to mankind, the modalities of human variability appear so far from those required for a coherent classification that the concept must be considered as of very limited use. In my opinion, to dismember mankind into races as a convenient approximation requires such a distortion of the facts that any usefulness disappears”. Jean Hiernaux (1964:41) The 1954 Supreme Court Desegregation Decision and “Scientific Racism” The U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing school segregation resulted in the organization of a movement which termed itself Scientific Racists. The individuals involved in this point of view included geneticists, psychologists, anatomists and anthropologists. They argued that the evidence for differences in intellectual abilities between racial groups had not as yet been completed worked out and that it was premature to bring together members of different races in the same schools and thus to encourage intermarriage. The Modern Concept of Race I Human biology reflects two kinds of evolutionary mechanisms: 1) Natural Selection working on populations to better adapt them to the conditions in their local environments. 2) Random mechanisms, like drift and migration, which modify the biology of a population, but are not adaptive. These socalled “Stochastic” changes certainly played a role in the earlier phases of human evolution, when population sizes were small. Human Races as Clines Clines are changes in the frequency (percentages) of an allele or feature across space. Clinal distributions characterize the world wide pattern of biological variation in humans. Thus, there is a reality to human races in that human populations differ. But, there is no reality to race as a set of distinct human groups with boundaries separating them from other such groups. Modern Concepts of Race II It is clear that both of these evolutionary processes were at work in the formation of modern human biological variation. However, when examining a specific biological trait, like hair color, for example, it is difficult to determine whether the variation in the expression of the feature is the result of selection or random processes. This confounds many studies of the relationships between a specific biological trait and the possible environmental pressures that underlie its presence in the population. Modern Concepts of Race III As we have seen, initial studies of race were based on the examination of obvious biological features, such as stature, hair color and other features. Modern investigations focus on genetic comparisons, both nuclear and mtDNA. These genetic studies document: 1) greater genetic variation exists within major geographic populations than between them. 2) human populations are remarkably homogeneous in their genetic materials. 3) African populations are more variable. Social Concepts of Race I Even though the notion of a pure race is a biological impossibility, it and other incorrect views of the biology of race have become part of our social concepts of race. The use of the term “race” is common in all facets of society. What is meant by race in these contexts, however, is very different from the biological notions of race as continuously distributed human populations whose allelic variation varies clinally. Social Concepts of Race II In present day society, the social concept of race is intertwined with the idea of an “ethnic group”. When the U.S. government uses the term race, it often is describing groups of people who share language, culture and a vague historical background. For example, the use of the term “Hispanic” does not have any biological meaning, but rather refers to peoples from parts of Central and South America and the Caribbean. Social Concepts of Race III Other socially constructed races, including African Americans (‘blacks’), Europeans (‘whites’), and Asians, have little biological reality and are often based on behavioral and cultural stereotypes, or simply on skin color. Many social agencies utilize the identification of the racial identity of people in order to determine the effectiveness of programs and thus for requests for Federal funding. Race and Racism The study of race continues to be one in which science, myth and bias often are intermixed into theories and claims that are difficult to sort out. For example, the work of people such as J. Philippe Rushton and others continue to be cited and used, much as earlier studies were, to support the ideas of inequalities between human groups. Popmap Race and Intelligence I Often, over the course of American history, one or another racial group has been designated as being inferior or superior in intelligence to other racial groups. Throughout the 19th century, various stereotypes were developed to support these claims. Many were simply the way Europeans justified the often times horrible treatment of colonial peoples under their control. Race and Intelligence II During World War I, the use of IQ tests in the U.S. for the first time suggested differences between various racial groups, but the data was ambiguous. Lately, the notion of IQ differences has become an important issue for discussion with the publication of books such as The Bell Curve. What are the realities to these discussions? Race and Intelligence III Remember, most of the so-called ‘racial groups’ in the U.S. are actually socially constructed groupings and have little biological reality. But, humans are different in their biologically based abilities. We are not created equal. All humans possess varying kinds of neurologically based abilities Race and Intelligence IV Some have math skills, others language skills, still other hand-eye-brain coordination skills. Most importantly, these abilities are not human population group specific, but are found across the human species. And, there remain strong cultural and social influences to IQ scores; there are no “culture free” ways to measure intelligence. A Summary Point: Intelligence It must be emphasized that, as we have seen, the notion of ‘intelligence’ in humans is a very complex one, involving many different skills and abilities. No one test, especially one founded in the concepts and ideas of a particular culture, can measure all the various talents every modern human possesses. Medicine and Social Races I Social notions about race do not have a basis in biological reality, but the use of these concepts obscures other kinds of variables. Many medical studies divide their samples into “Whites” and “Blacks” (African Americans). For example, studies of cardiovascular disease patterns often utilize these categories. However, African Americans have a very diverse biological history, with genetic contributions from Africans, Europeans and Native Americans. Medicine and Social Races II Because of the complexity of African American biological history, different individuals have different assortments of genetic variations, and may very well differ in their susceptibility to various diseases. Studies like this may overlook other risk factors, like socio-economic status, and overly stress biology. Some Question for Discussion Having examined the notion of race and its historical development, what are your views on the continued use of the term in our culture and in our language. Is this a concept that continues to be harmful? Do you have any suggestions for concepts or words to replace the concept and term ‘race’? Should we ignore the biological differences that mark world-wide human variation? Questions for Discussion How important is the concept of race in modern society?: A) not important, and because of the horrible history of race in recent human history, it ought to be put aside. B) it is important for everyone to know what their racial background is. C) the U.S. government uses race as a way to measure the effectiveness of social programs. it is useful in this context. D) there must be a better way to divide the human species into identifiable groupings. Human Races: A Summary Much of human biological variation is the result of adaptation to specific environments. Because of stochastic mechanisms, human population variation is complex; all variation cannot simply be ascribed to adaptation. The present mobility of the world’s people, allowing them to move around the planet with great ease means that population variation will slowly disappear as humans intermarry. Thus, over time, human races will increasingly become part of our history.