The Religious Hypothesis - The Richmond Philosophy Pages

The Religious Hypothesis

Richard Hare’s Criticisms of Flew

• Flew said that if you cannot imagine your belief to be wrong then the statement has no meaning

• Richard Hare responded to this offering his own parable to help us understand the strange nature of religious statement.

The Parable of the Paranoid Student

• “A certain lunatic is convinced that all dons want to murder him. His friends introduce him to all the mildest and most respectable dons they can find, and after each one of them has retired, they say, “You see, he doesn’t really want to murder you; he spoke to you in a most cordial manner; surely you are convinced now?” But the lunatic replies “Yes, but that was only his diabolical cunning; he’s really plotting against me the whole time, like the rest of them; I know it I tell you.”

However many kindly dons are produced, the reaction is still the same”

• Like the person who believes in the invisible gardener, the paranoid student cannot imagine being wrong, his statement ‘my teachers are out to get me’ is unfalsifiable

• And yet Hare argues that this belief is meaningful

– it has a deep influence on how the student approaches the world, how he forms other beliefs and how he lives his life. It is true that it operates so centrally within his belief system that it cannot be falsified, and all evidence is twisted to fit with this fundamental belief; but the very centrality of the belief means that it is deeply meaningful, contrary to what Flew has argued

We Are All The Same

• According to Hare we are all in some ways like the student – we all have fundamental beliefs or principles on which we base our actions and which we will never give up

• These thoughts and principles often form the very basis for our other beliefs, and they are both unverifiable and unfalsifiable

• Do you agree with Hare here?

“Blik”

• So Hare thinks beliefs like this are perfectly meaningful even though unfalsifiable

• He invented the word ‘blik’ to refer to such foundational thoughts and principles and argued that many religious beliefs fall into this category

• For example ‘God exists’ is a blik – it is a belief that informs their perspective on the world. They may never be willing to give it up, but the fundamental nature of the belief ensures that it remains important to them, and distinctly meaningful

Basil Mitchell’s Criticism of Flew

• Mitchell disagrees with the view that religious beliefs are unfalsifiable. He also offers a parable to make his point

The Resistance Leader

• Imagine your country has been invaded and a resistance movement develops to overthrow the occupiers. One night you meet a man claiming to be a resistance leader, and he convinces you to put your trust in him and the movement. Over the months you sometimes see the man act for the resistance, but sometimes you see him act against the movement. This troubles you: you worry that he might be a traitor, but your trust in him eventually overcomes your concerns and you continue to believe in him. Your belief that

‘the stranger is on your side’ is one you don’t give up, even though you see him do many things that is wrong.

• Mitchell argues that this belief in the resistance leader is meaningful, even though you refuse to give it up

• However, it is not a blik because there are many occasions where you doubt your own belief

• This doubt show that your belief is falsifiable

• Mitchell’s parable reflects the doubt believers sometimes have when they encounter great suffering in their lives

• This shows that Flew is wrong to think that believers simply shrug off evidence that goes against their beliefs

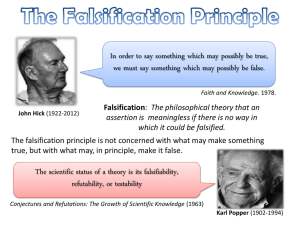

John Hick and The Revival of the

Religious Hypothesis

• Most philosophers argue that either the atheist or the believer is correct; either there is a God or there isn’t; either the religious hypothesis is true or it isn’t

• But as Flew pointed out, if there are no facts and no observations that will change the minds, and the statements, of believers, then what they say is meaningless

Eschatological Verification

• The philosopher John Hick responded to this attack by reviving the idea of verification

• Like Wisdom, Hick acknowledged the ambiguous nature of the world, and that observations appear to support both the claim that God exists and does not exist

• But Hick tries to show that ultimately the ambiguity disappears, and that in the afterlife religious statements can be verified and therefore the religious hypothesis is genuine

The Parable of the Celestial City

• “Two men are travelling together along a road. One of them believes that it leads to the Celestial City, the other that it leads nowhere; but since this is the only road there is both must travel it. During this journey they meet with moments of refreshments and delight, and with moments of hardship and danger. All the time one of them thinks this is a pilgrimage to the Celestial

City. He interprets the pleasant parts of the journey as encouragements and the obstacles of trials of his purpose. The other believes none of this and since he has no choice he enjoys the good and endures the bad.

When they do turn the last corner it will be apparent that one of them has been right all the time and the other wrong”

Eschatological Verification

• This points to the possibility of what Hick calls

Eschatological verification – verification after death in the next life

• Hick argues that many religious statements rest on the claim that there is an afterlife and they are meaningful because they can be verified in the afterlife

• For Hick such an experience would remove the grounds for rational doubt in the existence of heaven

Body

• Hick recognises the possibility of eschatological verification relies on the possibility of retaining personal identity through the process of death

• There are clearly difficulties with this idea: after people die their body decomposes – how if the body of which you are made has disappitated, can you possibly be thought to have survived? If someone subsequently appears in heaven, in what sense can it be said to be me?

Hick’s Solution

• To answer these questions Hick proposes 3 ‘thought experiments’ which try to show that a person appearing in an afterlife can be considered as the same person who died:

1.

First Hick asks us to imagine person X, disappearing in

America, while at the very same moment someone else, who is the exact double of X appears in Australia. If this happened would you consider the person appearing in Australia to be X?

2.

Now imagine that instead of disappearing, person X dies in

America, and at the very same moment their double appears in Australia. Wouldn’t we still say they were the same person?

3.

Finally, imagine that person X dies in America, and their double now appears, not in Australia, but in heaven. Again

Hick thinks that if we accept that it is the same person in scenarios 1 and 2 then it is the same person in this scenario too

Implications

• What these thought experiments are supposed to show is that resurrection is at least possible

• If we (or at least some of us) is resurrected in heaven, we will be in no doubt that it is heaven we are in