Propositional Attitudes

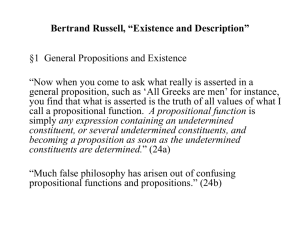

advertisement

Summer 2011 Monday, 07/25 Recap on Dreyfus • Presents a phenomenological argument against the idea that intelligence consists in manipulating symbols according to formal/syntactic rules (the PSS hypothesis). • Tries to describe the experience of becoming an expert in “slow motion”: Novice Advanced Beginner Competent Proficient Expert. • Claims that paying close attention to this progression reveals that being an expert is not a matter of following “internalized” rules at all. • It is, in fact the other way around: becoming an expert is getting away from rule following altogether. Knowing How vs. Knowing That • Knowing-that = Propositional Knowledge. Knowing some set of facts, e.g. the fact that Paris is in France or the fact that one should do such-and-such in a certain situation. • Knowledge-how = “Procedural knowledge”, having an ability to do something, e.g. to drive a car, ride a bike, ski, weld metal, etc. Kinds of Knowledge • Knowledge-that is fundamental. Many types of knowledge, e.g. knowledgewhere/when/who/what, may be understood in terms of knowledge-that. • But some kinds of knowledge, e.g. knowledge by acquaintance (many languages have special words for this!), may not be understood in this way. • It’s an open, controversial question in philosophy how knowledge-how relates to knowledge-that. Propositional Attitudes • • • • • • I think that Paris is pretty. You hope that Paris is pretty. Jon believes that Paris is pretty. Paul says that Paris is pretty. Laura and Jim wish that Paris is pretty. These people expect that Paris is pretty. The bold terms seem to refer to types of mental states. The underlined clauses seem to refer to propositions. A PROPOSITIONAL ATTITUDE is a mental state that relates someone (e.g. a person) to a proposition. Propositions are the intentional objects of propositional attitudes. Propositions • Mind/Language Independent. Two people can be related to the same proposition, even if they don’t share a language. • Are Abstract. You can’t encounter or them or perceive them through the senses. • Can be true/false. The conditions in which a proposition would be true/false are essential to the proposition. • Often used in common sense, psychological explanation, e.g. I believe the same thing that she does, she said what I wanted to say, we both expect the same thing to happen. Propositions • We can think of propositional attitudes asmental states that are about propositions, or that involve “grasping” them. • Believing, hoping, desiring, expecting (and so on), are all different ways of entertaining (or grasping) propositions. Propositional Attitudes Tricky questions arise, among them: 1. What exactly are the mental states that relate us to propositions? What is a thought, a belief, a hope, a desire? 2. How does a mental state, of whatever stripe, manages to relate a person to a proposition? What is it to “grasp” a proposition? 3. What explains the difference between the various ways of entertaining propositions (e.g. believing, hoping, desiring)? 4. Why is it that entertaining some propositions, in certain ways, leads us to systematically (rationally, intelligibly) entertain certain others, in certain appropriate ways? What’s the scientific explanation of this fact? Representational Theory of Mind (RTM) A framework for understanding the propositional attitudes, defined by these claims: 1. Propositional attitudes pick out computational relations to internal representations. 2. Mental processes are causal processes that involve transitions between internal representations. Fodor “To a first approximation, to think “it’s going to rain; so I’ll go indoors” is to have a tokening of a mental representation that means I’ll go indoors caused, in a certain way, by a tokening of a mental representation that means, it’s going to rain.” (Fodor) Fodor • “Folk Psychology”, or our common sense theory of the mind is largely correct. • Thoughts, beliefs, desires (and so on) are real innerstates. • These states are built out of symbols (e.g. brain states and processes) that causally interact with other mental states. Fodor • Science will validate our common sense understanding of ourselves by identifying inner states whose meanings and structures closely match the contents and structures of daily ascriptions of propositional attitudes (with some room for idealization/mistakes). Churchland • There are no inner states that closely match our talk of propositional attitudes, i.e. there are no beliefs, hopes, desires, and so on. • As science progresses, we will drop talk of such entities and adopt an entirely new, scientific way of talking about our psychology. Churchland “We need an entirely new kinematics and dynamics with which to comprehend human cognitive activity. One drawn, perhaps, from computational neuroscience and connectionist AI. Folk psychology could then be put aside in favor of this descriptively more accurate and explanatorily more powerful portrayal of the reality within.” Dennett • • • Tries to steer a middle course between Fodor and Churchland. Like Churchland, anticipates no close match between the folk and scientific understanding of ourselves. But holds that the goodness of the common sense understanding is established independently of particular facts about implementation. Dennett • • Common-sense psychology is a useful tool for making sense of the mental lives and daily behavior of rational beings. It is a special case of the “design stance” that we take towards artifacts, a way of understanding things in reference to what they’re supposed to do. Dennett • Our common sense psychology is “a rationalistic (i.e. rationality-assuming) calculus of interpretation and prediction—an idealizing, abstract, instrumentalistic interpretation method that has evolved because it works and that works because we have evolved.” Dennett • • • Dennett’s view is complex. He does not claim that there are no beliefs. Instead, folk-psychology works because there exist real, objective patterns in human and animal behavior that are fully observer independent. Mental states are real in the same sense as “abstracta” such as centers of gravity or the equator are real. We’ll talk a lot more about each of these three views in the next three days!