Attractiveness Preferences

• Adults & children:

– Prefer attractive over unattractive individuals

– Use similar standards for attractiveness

evaluation

– Show cross-cultural similarities in

attractiveness judgments

• Numerous studies through 1970s and 1980s

Historical Assumptions

• Gradual learning through exposure to

socialization agents (e.g., parents, peers)

and media

• Standards of attractiveness vary across

historic time, generations, and cultures

Origins of Attractiveness

Preferences

• Through extensive cultural input

• Learning processes (operant conditioning,

observational)

• Preferences shouldn’t become apparent until

age 3-5 years

• “Eye of the beholder” theory

• However, lack of empirical work

Empirical Methods

• Comparison of historical evidence (e.g.,

painting, sculpture, written descriptions, etc.)

• Cross cultural, longitudinal studies

• Look for attractiveness preferences in young

infants

Judith Langlois

• Developmental psychologist

• Social development, emphasis on origins of

social stereotypes, particularly facial

attractiveness

• Currently at University of Texas, Austin

Why Start with Facial

Attractiveness?

• Infant visual system

• Part of body most seen from early in life

• In humans, primary means of individual

identification

• Facial expressions

Infants Learn about Faces Early

• Infants prefer mother’s face to female

stranger within 45 hours of birth (Field et al.

1984)

• 12 to 36 hour old infants suck more to see

video of their mothers’ faces as opposed to

female stranger’s (Walton et al. 1992)

Development

• 3 months

– Discriminate familiar from unfamiliar faces

• 6 months

– Distinguish faces by age and sex

– Preferences for happy over angry faces

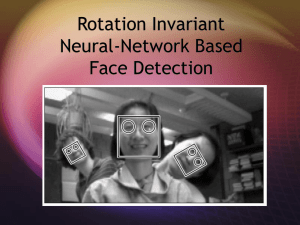

Gaze Time

• Show two paired side-by-side images

• Record amount of time gazing at each

image

• More time assumed to indicate greater

preference

Controls

• Differences between faces other than

attractiveness

– E.g., hair colour, skin colour, hair style, age

effects, sex, facial expression, etc.

• Can be quite challenging

Langlois et al. (1987)

• Undergraduates rated colour slides of adult

Caucasian women

• Selected 8 attractive and 8 unattractive

faces

• Paired images for gaze time testing

• Within-trial (attractive paired with

unattractive)

• Across-trial (two similarly ranked faces)

Results

• 34 six to eight month old infants

– 71% gazed longer at attractive faces

– 62% spent less time looking at paired

unattractive than paired attractive faces

• 30 two-three month old infants

– 63% gazed longer at attractive faces

– No significant differences for across-trial test

– Attentional processes? Focus on whatever seen

first?

Langlois et al. (1991)

• Faces rated for attractiveness by

undergraduates

• Adult Caucasian males, adult AfricanAmerican females, infant faces

• Six month old infants

• Infants prefer to look at attractive over

unattractive faces

Conclusions

• Infant preferences established at very early

age

• Gender, ethnicity, age not relevant to

preferences

• Too young for socialization model to

explain

• Preferences too diverse for socialization

model to explain

What is Beautiful is Good

• Attractive people possess positive attributes

(e.g., kindness, socially outgoing, etc.)

• Unattractive people possess negative traits

(e.g., mean, stupid, unpleasant, etc.)

• Transferring from perceptual to behavioural

• Common in adults (e.g., Dion, 1973)

• What about infants?

Langlois et al. (1990)

• Test that gaze time equates to beauty is

good in adults

• Used 12 month olds

• Infants interacted with female adult stranger

in attractive or unattractive lifelike latex

mask

• Stranger followed “scripted behaviours”;

rated as identical by observers for both

conditions

Results

• Strong social preference for “attractive” stranger

• More positive affect towards “attractive” stranger

• Similar findings where 12 month olds given two

dolls to play with; one with attractive, one with

unattractive head

• Infants’ visual preferences for attractive faces

functionally equivalent to social preferences for

attractiveness in adults and older children

What Makes a Face Attractive?

• Langlois suggests averageness

• Galton (1878) photo-averaged faces of criminals;

inadvertently found regression toward the mean

• Langlois & Roggman (1990)

– Morphed up to 32 faces; 16 & 32 morphs most

attractive

• Langlois lab

By “Average” We Mean…

• Average faces not average in attractiveness

• Average in terms of the mean, or central,

tendency of facial traits of the population

• Average faces are above average in

attractiveness, in terms of how much

infants, children, and adults like them, and

in terms of how much people consider them

good examples of a face

An Adaptationist Explanation

• Individuals showing population averages of

traits likely free from aversive genetic

conditions (e.g., mutations, deleterious

recessives, etc.)

• Selection favours mate choice of individuals

with average morphological traits

Infant and Child Facial

Appearance

• Affects adult interactions and behaviour

• Unrelated adult females punished

unattractive children more than attractive

children

• Berkowitz & Frodi (1979), Dion (1972,

1974)

Child Physical Abnormalities

• Mothers treat these children differently

• Congenital facial anomalies; mothers less

verbal and more controlling (Allen, et al. 1990)

• Cleft lip; mothers smiled at, spoke less, and

imitated less (Field & Vega-Lahr 1984)

• Overall, less parental care for these children

Langlois, et al. (1995)

• What about attractiveness in normal

populations of children?

• Infant attractiveness and maternal attitudes

and behaviours

• 173 mothers and their infants

• Three ethnic groups (white, African

American, Mexican American)

Method

• Observers coded frequency and duration of

63 maternal and 50 infant behaviours at

newborn and 3 months

• Questionnaire assessing parenting attitudes

and knowledge

• Colour photos of infants’ faces and mothers’

faces rated for attractiveness by adults

Findings

• Mothers of attractive newborns more

affectionate, showed greater caregiving, and

more attention to their infants

• Mothers of unattractive newborns more

likely to say their infants interfered with

their lives, but did not express attitudes of

rejection to their infants

• Maternal attractiveness had no effect on

results

Infant Phenotype and Health

• Low body weight (LBW)

• Health risks

– Infant and child health problems: morbidity,

physical, neurological, behavioural deficiencies

(Sweet et al. 2003)

• Parental care

– Less affection, attention, general care (Mann

1992)

Volk et al. (2005)

• Do infant facial cues indicating LBW

influence adults’ perceptions of infants and

desire to give parental care?

• Hypothetical adoption paradigm

• Adults shown

– Unaltered faces of infants and children

– Faces digitally manipulated to simulate LBW

• Rate faces for cuteness, health, preference

for adoption

Stimuli

• Five children’s faces

– 18 months and 48 months

– Normal

– Morphed to represent 10% reduction in body

weight

Findings

• Normal faces rated as significantly cuter,

healthier, and more likely to be adopted

• Adult women gave significantly higher

ratings on all measures than men

EP Implications

• Assessments of health and fitness made for

infant and child faces

• Positive correlation between facial

attractiveness and health issues

Investment

• Gestation expensive

• Childrearing even more so

• Reluctance to expend energy on low-viable

offspring

• Differential reproductive success and selfish

gene theory

• Put energy into best offspring

Female/Male Differences

• Reproductive and rearing costs higher for

females

• Volk, et al. (2005) supports this

– Females need to be more selective