Fig. 7 Cancer cell signaling pathways and the cellular processes

advertisement

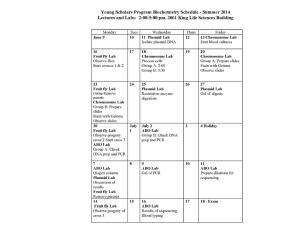

The History of Cancer and Its Treatments Osher Lecture 5 May 8, 2013 Recent History (after a reminder of how DNA encodes proteins) Russell Doolittle, PhD DNA: A Double-Helix Sugars phosphate links (desoxyribose) One base pair A:T G:C Complementary nitrogen bases (A:T, G:C) directed inward Proteins are composed of long chains of amino acids. During the 1950’s techniques were developed that allowed the sequence of amino acids in a protein to be determined. The sequence of amino acids in a protein is simply the order in which the amino acids occur, starting at the amino-terminus. During the 1960’s and 70’s, numerous proteins were “sequenced” and the relationship of proteins and organisms at the molecular level was firmly established. In 1978, new cutting and pasting techniques set the stage for DNA sequencing and eventually to the Human Genome project. It is much easier to find the sequence of a protein by translating the DNA sequence of its gene than by the old chemical methods. Current methodology allows DNA sequencing to be conducted on a massive scale. What all cancers have in common is DNA damage that leads to run-away cell division. It is a kind of cellular evolution where natural selection favors those that divide most rapidly. The DNA damage results in altered proteins, the interactions of which often promote more DNA damage. It is much easier to disrupt a protein’s structure and function than it is to make it more active, but both kinds of alteration occur. DNA RNA Protein DNA is composed of 4 kinds of unit: A, G, C, T. RNA is composed of 4 kinds of unit: A, G, C, U. proteins are composed of 20 kinds of unit: amino acids A triplet code (three units of DNA or RNA) is necessary to distinguish 20 amino acids. For example, AAA (DNA) is transcribed as UUU, which is translated as the amino acid phenylalanine. If one of the units in the DNA is mutated, e.g., AAA -> ATA, this will be transcribed as UAU, which is translated as the amino acid tyrosine. Coding ATGAGATACTCCTTTAAAGGG…etc DNA: TACTCTATGAGGAAATTTCCC…etc RNA: AUGAGAUACUCCUUUAAAGGG…etc RNA: AUG AGA UAC UCC UUU AAA GGG…etc (taken three at a time) Protein: Met-Arg-His-Ser-Phe-Lys-Gly…etc Protein: MRHSFKG…etc (in single-letter code) Synonymous mutations base substitution gives rise to same amino acid Non-synonymous mutations base substitution gives rise to different amino acid The ratio of non- synonymous mutations to synonymous ones is an index of non-random survival. Today the determination of DNA sequences is a highly automated process. Most protein sequences are gotten by translating (decoding) DNA sequences. It is possible to sequence the DNA of cancer cells taken directly from tumors to see what changes have occurred during their lifetime compared with nearby healthy tissue. A reminder about signaling pathways. The cell is crowded. Bumping into old pals in the subway crowd. Things can go awry during all these cell divisions. Gene Expression Although all your cells (well, almost all) have all the DNA encoding all your genes, different cells express different genes. They are able to do this because the expression of genes is highly regulated by factors that prevent or encourage copying to RNA (by the enzyme RNA polymerase) . Regulation occurs at the gene product stage also, by activating or inactivating enzymes and other proteins. Various forms of somatic damage to DNA Simple base replacements (e.g., A for G, C for T, etc.) Deletions or insertions of pieces of DNA. Chromosomal translocations (exchanges of pieces). Amplification (increase in “copy number”). Speaking very generally, there are two kinds of altered proteins in cancer cells. In one kind, the mutated protein acquires new power: “gain-of-function.” Many of these are hyperactive kinases (often “gatekeepers”). In the other kind, the mutated protein is inactivated. Many of these are “tumor suppressors” (“caretakers”). Generally speaking, it is easier to make a drug that can inactivate a “gain-of-function” sort than it is to find one that can restore function to a “caretaker.” An example of a suppressor gene: p53 and cell death More than half of all cancers involve a gene product called p53. In 1993, Science magazine named p53 “Molecule of the Year” and had its structure on the cover. In an accompanying editorial the hope was expressed that “a cure of a terrible killer (would occur) in the not too distant future.” The “hope” was that damaged molecules of p53 could be fixed. p53 is a tumor suppressor; here is how it works. When p53 is not working properly, cells with damaged DNA keep dividing. Moreover, the progeny of those cells with damaged DNA spawn even more cells with even more damaged DNA. Those progeny cells with stuck accelerators quickly outrace the others. Carriers of a mutated p53 gene (in their genome) have a 95% lifetime risk of developing cancer. Now for the recent stuff. A few terms: WGS = Whole Genome Sequencing. exome = the 1-2% of the genome that is expressed as protein. sbs = single base substitution = snv = single nucleotide variant. CNV = copy number variation (more than one gene for the same protein as a result of gene duplication) cancer susceptibility genes (caretakers and gatekeepers). driver gene mutations, directly or indirectly, confer a selective growth advantage for the cell in which they occur. passenger gene mutations have no direct or indirect effect on the growth of the cell in which they occur. The March 29, 2013 issue of Science carried a special section on Cancer Genomics Many of the following slides are from those very recent articles. The main theme has to do with the sequencing of cancer genomes. colorectal Numbers of non-synonymous mutations per cell line lung melanoma colorectal breast AML CLL ALL Fig. 2 Genetic alterations and the progression of colorectal cancer. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS Fig. 3 Total alterations affecting protein-coding genes in selected tumors. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS p53 complex PIK3CA mutant PIK3CA Fig. 4 Distribution of mutations in two oncogenes (PIK3CA and IDH1) and two tumor suppressor genes (RB1 and VHL). B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS B. Vogelstein et al, Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Fig. 5 Number and distribution of driver gene mutations in five tumor types. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS Fig. 6 Four types of genetic heterogeneity in tumors, illustrated by a primary tumor in the pancreas and its metastatic lesions in the liver. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS Fig. 7 Cancer cell signaling pathways and the cellular processes they regulate. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS Fig. 8 Signal transduction pathways affected by mutations in human cancer. B Vogelstein et al. Science 2013;339:1546-1558 Published by AAAS Like snowflakes and fingerprints, no two cancers are exactly alike. However, there are a limited number of very susceptible locations in the genome, and the same signaling pathways are disrupted in many different settings. On other fronts, there have been some spectacular successes recently in treating adult leukemias (AML and CML) by modifying the patient’s own white cells that makes them attack cancer cells. However, The future: cancer prevention by DNA screening It will soon be routine to have some aspect of WGS performed at birth (think PKU screening at present) or during pregnancy. It will also be possible to screen for certain cancers before they become malignant, perhaps including lung (sequence DNA from cells in sputum), colon (DNA from stool samples), and prostate (urine) Treatment will take various guises, including the usual routes (surgery), as well as very targeted chemotherapy directed at the altered signaling pathways. But who will pay? Beware the military-industrial-complex (Eisenhauer, 1961) Today we would say: Beware the pharmaceutical-congressional-complex.