Classic Greek and Roman Art

Classical Greek and Roman Art

Greek Temple of Poseidon Roman Colosseum

The art of Ancient Greece is usually divided stylistically into three periods: the Archaic, the Classical and the Hellenistic. The Archaic age is usually dated from about 1000 BC, although in reality little is known about art in Greece during the preceding 200 years

(traditionally known as the Dark Ages). The onset of the Persian

Wars (480 BC to 448 BC) is usually taken as the dividing line between the Archaic and the Classical periods, and the reign of

Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC) is taken as separating the

Classical from the Hellenistic periods.

Art historians generally define Ancient Greek art as the art produced in the Greek-speaking world from about 1000 BC to about 100 BC. They generally exclude the art of the

Mycenaean and Minoan civilizations, which flourished from about 1500 to about 1200 BC. Despite the fact that these were Greek-speaking cultures, there is little or no continuity between the art of these civilizations and later Greek art.

At the other end of the time-scale, art historians generally hold that Ancient Greek art as a distinct culture ended with the establishment of Roman rule over the Greek-speaking world in about 100 BC.

Kouros

Lifesize, circa 540 B.C.

From the island of Melos .

Archaic Art

The Archaic sculptures are silent witnesses to the extraordinary development western society was about to undertake. The Kouros and Kore statues stand before a cultural revolution, all muscles tense, like a spring about to burst with energy into an extraordinary wave of classical thought. They stand with smiles frozen with meaning as if they knew what was about to occur

Zeus of Artemision

Bronze, circa 460 - 450 B.C.

2.09 m (6' 10.5") high,

2.10 m (6' 10.75") fingertip to fingertip.

Found in the sea near cape Artemisio

The Classical Period

From the National Museum of Athens:

“The ancient Greek Artist invented his own self and became the creator of god and man alike in a universe of perfect formal proportions, idealized aesthetic values and a newly found sense of freedom. This was a freedom from barbarism and tyranny.”

Poseidon of Melos

Marble, circa 140 BC.

Hellenistic Art

The subtle implications of greatness and humility of the high Classical era are replaced with bold expressions of energy and power during the moments of tension as evident in the poses depicted during the Hellenistic era.

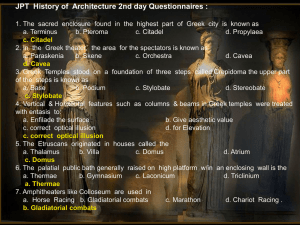

ARCHITECTURE:

Temples were Post and Lintel constructions made mostly of stone and marble. The base of the temple was called the stylobate. The Peri-style was a row of columns that surrounded all four sides of the temple and supported a lintel area called the entablature.

The top most element of the entablature, the cornice, supported a peaked roof. It was made of a continuous band of carved stone called moldings. At each end, the horizontal cornice of the entablature and the raking (slanted) cornices of the roof defined a triangular gable called the pediment. There were three basic orders of columns during this period: the Doric, Ionic, and

Corinthian.

The Greeks developed three architectural systems, called orders, each with their own distinctive proportions and detailing. The Greek orders are:

Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

Doric Ionic Corinthian

The Doric style is rather sturdy and its top (the capital), is plain. This style was used in mainland

Greece and the colonies in southern Italy and Sicily.

The Ionic style is thinner and more elegant.

Its capital is decorated with a scroll-like design (a volute). This style was found in eastern Greece and the islands.

The Corinthian style is seldom used in the

Greek world, but often seen on Roman temples. Its capital is very elaborate and decorated with acanthus leaves.

The Doric order columns were formed of round sections called drums which were joined by metal pegs. A fluted shaft rose from the stylobate without a base. At the top of the shaft was the necking. The capital sits on the necking; it is made of the rounded echinus and the tablet-like abacus.

The entablature of the column included the architrave, the frieze, and the cornice.

The height of Ionic order columns was about nine times the diameter of the column at its base; the

Doric order had a five and a half to one ratio. The flutes in the shaft were deeper and closer together and were separated by flat surfaces called fillets. On top of these columns was a thin cushion-like abacus with scrolled volutes.

The Corinthian order had elaborate capitals decorated with acanthus leaves and rosettes. They often had scrolled elements at the corners and a boss, or projecting ornament at the top center of each side.

Greek

Ancient Greek art is mainly in five forms: architecture , sculpture , painting , painted pottery , and music .

Greek music includes the lyre, pipes, and singing, and around 500 BC gradually developed branches like Greek plays (which always involved music) and Greek philosophy , which tried to figure out how music and numbers related to each other.

Architecture includes houses, religious buildings like temples and tombs, and public building like city walls, theaters, stadia, and stoas.

Sculpture includes small figurines and life-size statues, but also relief sculptures which were on the sides of buildings, and also tombstones.

We have very little Greek painting from the Classical period; most of what we have is from the Bronze Age . The paintings were painted on walls, as decoration for rooms, like murals or wallpaper. On the other hand, we have a good deal of painted pottery from all periods of Greek history (down to the Hellenistic ).

http://www.historyforkids.org/learn/greeks/art/greekart.htm

Acragas, Temple of Concord

The Acropolis at Athens

View of the entire complex

Athens, Parthenon, East facade

Temple of

Poseidon

60 x 19.55 m (196 x 64 ft)

Consisting of 39 columns and a cella with three naves c. 450 BC

Marble statue of a kouros (youth) , ca. 590 –580 B.C.; Archaic Greek, Attica

This kouros is one of the earliest marble statues of a human figure carved in

Attica. The rigid stance, with the left leg forward and arms at the side, was derived from Egyptian art. The pose provided a clear, simple formula that was used by Greek sculptors throughout the sixth century B.C. In this early figure, geometric, almost abstract forms predominate, and anatomical details are rendered in beautiful analogous patterns. The statue marked the grave of a young Athenian aristocrat.

On the shoulder, a seated woman, perhaps a goddess, is approached by four youths and eight dancing maidens; on the body, women are making woolen cloth. One of the most important responsibilities of women in ancient Greece was the preparation of wool and the weaving of cloth. Here, in the center, two women work at an upright loom. To the right, three women weigh wool. Farther to the right, four women spin wool into yarn, while between them finished cloth is being folded.

The Amasis Painter is named after the potter, Amasis, who produced the vases

.

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask) , ca. 550 –530 B.C.; Archaic

Attributed to the Amasis Painter

Greek, Attic

Bronze diskos thrower , ca. 480 –460 B.C.; Classical

Greek

Bronze; H. 9 5/8 in.

This superlative bronze embodies the highest achievements of the early

Classical period. The athlete is about to swing the diskos forward and over his head with his left hand, then transfer it to his right hand, and finally release it with the force of the accumulated momentum.

The beauty of the statuette lies in the calm and concentrated physiognomy that forms part of a perfectly developed and disciplined body.

This hydria, like all Greek art, is marked by clearly defined parts organized into a harmonious wellproportioned whole. The plain body swells gently to the shoulder zone, which turns inward with a soft cushionlike curve. The shoulder is decorated with a simple shallow tongue pattern that echoes the vertical ribbing on the foot. The neck shoots from the shoulder to a flaring mouth from which the bust of a woman seems to emerge. The figure, which belongs to the vertical handle of the vessel, wears a peplos and her serene face is framed by carefully detailed hair. Rotelles with a rosette pattern give a semblance of outstretched hands. The inscription on the mouth indicates that this hydria was a prize awarded at games for the goddess Hera at her sanctuary in Argos in the

Peloponnesos.

Bronze hydria (waterjar) , mid-5th century B.C.; Classical

Greek, Argive

Marble grave stele of a little girl , ca. 450 –440 B.C.;

Classical

Greek

Marble, Parian; H. 31 1/2 in.

This stele was found on the island of Paros in 1775. The gentle gravity of the child is beautifully expressed through her sweet farewell to her pet doves. Her peplos is unbelted and falls open at the side, and the folds of drapery clearly reveal her stance. Many of the most skillful stone carvers came from the Cycladic islands, where marble was plentiful. The sculptor of this stele could have been among the artists who congregated in Athens during the third quarter of the fifth century

B.C. to decorate the Parthenon.

Winged Victory of Samothrace

Greek

Marble, h. 3.28 m (11 ft)

Found on the island of Samothrace

Around 190 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Bronze statue of Eros sleeping , 3rd century B.C.

–early 1st century

A.D.; Hellenistic or Augustan period

Greek or Roman

Venus de Milo

Greek

Parian marble, h 2.02 m (6 1/2 ft)

Found at Milo

130-120 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) , ca. 360 –350

B.C.; Late Classical

Ancient sculpture was painted. Although faint remnants of polychromy can be discerned on some objects, the original effect has been lost.

This vase provides a rare example of the actual painting process, in which the encaustic pigments were mixed with wax. On the obverse, an artist paints a lion-skin on a marble statue of Herakles, surrounded by two assistants,

Zeus and Nike. To the left of the statue, a youth tends a charcoal brazier on which the wax mixture and the tools are being warmed. The artist, to the right, is recognizable by his cap and by his garment worn so as to afford maximum coolness and freedom of movement.

A small container in his left hand holds the pigment, which he applies with a tool like a knife or spatula. Zeus and a Nike

(personification of victory) watch from on high, and at the far right Herakles himself approaches. On the reverse of the krater,

Athena is seated with one of Dioskouroi.

Hagesandros, Athenodoros and

Polydoros of Rhodes

Laocoon and his sons c. 175-150 BC

Marble, height 242 cm (95 1/2 in)

Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican

Roman Art

Fragments of Constantine - Capitoline Museum in Rome

The Arch of Constantine, though, is a little different from the earlier arches, because Constantine was reminding people about a civil war, not a war against foreign enemies. Titus had conquered the Jewish revolt , and

Septimius Severus had conquered the

Germans , but Constantine had conquered another Roman emperor.

On top of the arch, Constantine had an inscription carved that reminded people of his victory. It's carefully phrased, so that while it refers to God, it doesn't specify which god - a Roman god like

Jupiter , or the Christian God? In 312

AD, Constantine was already a

Christian, but he wasn't ready to put it on a public monument yet.

Around the lower part of the arch, just over the side archways, Constantine put pictures of the battle itself.

Arch of Constantine , 315 C.E., Rome

The Forum

The site of ancient government buildings in the center of Rome.

The

Colosseum

When Vespasian became the new Roman Emperor in 69 AD, he wanted everyone to know that he cared about the people and was going to take care of them and not live luxuriously as Nero had. He tore down a lot of Nero's Golden House and made the land into a public park.

Vespasian also used his share of the gold from the looting after the First Jewish

Revolt to pay for the construction of a new amphitheater where the Golden House had been. Because Vespasian's architects used the new method of building in concrete, he was able to build quickly and cheaply. We call this amphitheater the

Colosseum, after the giant statue of Nero that stood near it. But its ancient name was the Flavian Amphitheater. Building the amphitheater made Vespasian very popular in Rome.

The Colosseum was a place where a lot of people could sit and watch entertainment. The entertainment was mostly people killing animals, or people killing each other. It was almost exactly like a football stadium today. It was built of concrete and marble and limestone.

The reason it looks so terrible in this picture is that a lot of the seats were made of marble and people have stolen them away over the years and burned them in lime kilns to make mortar and cement. The floor has also been taken away, so you can see the rooms in the basement where the Romans kept the animals and the equipment and stuff.

Discobolos (Discus Thrower) c. 450 BC

Roman marble copy after the bronze original by Myron height 155 cm (61 in)

Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome

During his lifetime, Augustus did not wish to be depicted as a god (unlike the later emperors who embraced divinity), but this statue has many thinly-veiled references to the emperor's "divine nature", his genius .

Augustus is shown barefoot, which indicates that he is a hero and perhaps even a god, and also adds a civilian aspect to an otherwise military portrait. Being barefoot was only previously allowed on images of the gods, but it may also imply that the statue is a posthumous copy set up by Livia of a statue from the city of Rome in which Augustus was not barefoot.

The small Cupid (son of Venus) at his feet

(riding on a dolphin, Venus's patron animal) is a reference to the claim that the Julian family were descended from the goddess Venus , made by both Augustus and by his great uncle

Julius Caesar - a way of claiming divine lineage without claiming the full divine status, which was acceptable in the Greek East but not yet in Rome itself.

Prima Porta Augustus 1 st Century

Rome

The Pantheon

In the time of the Roman Emperor Augustus, about 10 BC, one of his generals, a man named Agrippa, built a temple in the middle of downtown Rome "to all the gods". A temple to all the gods was called a Pantheon, which means all gods

(pan= all, theon=of the gods, in Greek). Now this temple was probably very fine, but we don't really know, because in 80 AD, in the reign of Titus, it burned down in a fire. Domitian built a new temple there, and THAT one burned down too.

Around 120 AD Hadrian built a THIRD temple there in a more modern style

(modern for 120 AD anyway!). This is the temple we have today. But to honor

Agrippa, Hadrian left a message over the door saying that Agrippa had built the temple, as you can see in the picture. You might think, well, that doesn't really look like much of a place. And from the outside it really doesn't seem very impressive. The Pantheon is built like a Greek temple on the front, with eight columns across the front like the Parthenon, and a pediment on top of that.

But on the INSIDE the Pantheon is one big giant dome, the largest dome ever built in the world up to that time - 43 meters in diameter (142 feet), and 43 meters from the floor to the top of the dome.

http://www.historyforkids.org/learn/romans/architecture/pantheon.htm

To hold up this dome, the walls had to be made of brick and concrete six meters thick - about twenty feet! The coffering in the dome lightens it a little, but it's still very heavy. No dome anything like this size was built anywhere in the world until the Duomo of Florence in the 1400s, more than a thousand years later. Even then, the Duomo dome is about the same size, and no other one of that size has ever been built, until the 1800s with reinforced concrete.

The hole in the top of the dome - the oculus- is open to the sky. Some people say the dome is so high that rain evaporates before it hits the floor, but that's not true on rainy days, the marble floor just gets wet.

The reason the Pantheon is in such good shape is that the Roman Emperor

Phocas gave the building to the Popes in 609 AD for a Christian church, and the

Popes since then have taken good care of it.

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the

Villa of P. Fannius Synistor , ca.

40 –30 B.C.; Republican; Second

Style Roman Fresco

Room M of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79, functioned as a bedroom.

Bronze portrait statue of a boy , late 1st century B.C.

–early 1st century A.D.; Early Imperial,

Augustan

Roman

This bronze figure portrays a young member of a wealthy

Roman family. The style of the idealizing portrait clearly indicates that the subject wished to be shown in the guise of a prince of the imperial family.

Marble bust of a bearded man , ca. A.D. 150 –175; Mid-Imperial,

Antonine

Roman

This masterful portrait bust represents a vigorous middleaged man who turns his head slightly to his right and stares into the distance with a critical, penetrating gaze. The broad, square face is carefully modeled; wide furrows cut into the low forehead and at the corners of the eyes, adding to the intensity of the expression. One assumes that the sitter was a contemporary man in the guise of a thinker rather than this being a portrait of a practicing philosopher.

Marble portrait of the emperor

Caracalla , ca. A.D. 217 –230;

Mid-Imperial, Severan

Roman

Marble; H. 14 1/4 in.

This head is from a statue, other fragments of which survive. Caracalla abandoned the luxuriant hair and beard of his predecessors for a military style characterized by close-cropped curls and a stubble beard. Often finely carved, his portraits look compact but convey an explosive energy

Aqueducts - Roman architects and hydraulic engineers built the magnificent water-transporting bridge known as Pont du Gard 2,000 years ago. Photo credit: ©

Samo Trebizan/iStockphoto

Is it Greek or is it Roman?

Preferred Structure

Walls

Trademark Forms

Greek

Temples to Glorify Gods

Roman

Civic Buildings to honor empire

Made of cut stone blocks Concrete with ornamental facing

Rectangles, straight Lines Circles, curved lines

Support System

Column Style

Sculpture

Painting

Subject of Art

Post and Lintel

Doric and Ionic

Idealized gods and goddesses

Stylized figures floating in space

Mythology

Rounded arch, vaults

Corinthian

Realistic human beings, idealized officials

Realistic images with perspective

Civic Leaders, military triumphs