Using Patient`s Own Medication in Hospital

advertisement

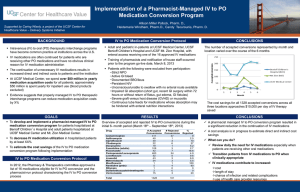

Using Patient’s Own Medication in Hospital: Is it a Safer Approach to Medication Administration? Brock Delfante Pharmacist Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Delivering a Healthy WA Background • Medication supply to patients is a fundamental role of hospital pharmacy departments • At SCGH, medications are currently supplied to inpatients predominantly through an imprest system and through supply of non-imprest medications from pharmacy to the ward • Administration of medication is often facilitated by bedside drawers • There are a number of system characteristics which increase the likelihood of medication errors, and contribute to both time and financial inefficiencies Background • POM schemes are used in many countries to streamline supply processes • Benefits include: – – – – Assists medication reconciliation process1, 2, 3, 4 Patients can continue taking medications they are familiar with1, 3 Pharmacists are aware of what supplies the patient requires1, 3 Pharmacists can prepare medicines ready for discharge by knowing what additional supplies are required1 – Significant cost savings to the hospital1, 3, 4 • At SCGH, although not encouraged, Nursing Practice Guidelines allow for the use of POMs • The aim of this study was to determine potential benefits to medication safety through implementation of a POM scheme at SCGH Methodology • Post-operative patients admitted to orthopaedic ward were allocated either to POM group or non-POM group Patients using hospital supplies of medicines only n=18 Patients using POMs n=30 – Total sample n=48 • Information was gathered through a standardised data collection form using the NIMC, PAC documentation and a medication drawer audit to collect data • Exclusions: – – Patients taking less than two regular medicines Patients using a medication administration aid (eg Webster-Pak®). Methodology Patient initial presentation to emergency Patient initial presentation to pre-admissions clinic Patient admitted to ward following surgery Medications assessed and stored in drawer Supply of required medications from pharmacy Administration facilitated by medication drawer Results Table 1. Patient group characteristics comparison POMs not used Mean (n=18) POMs Used Mean (n=30) Total Mean (n=48) P Value Drugs on NIMCa 7.6 8.9 8.5 0.1168 Drugs present in drawer 9.1 9.6 9.4 0.5174 Patient went through PAC 5.5% 87% 56% - aExcludes medications for prn use and IV medications Table 2. Bedside drawer and NIMC audit results for patients using, or not using POMs during admission POMs not used n (%) (n=18) POMs Used n (%) (n=30) Total n (%) (n=48) P Value Patients with missing drugs 56 23 35 0.0169 Patients with incorrect drugs 72 50 58 0.0343 Patient with a ceased drug in drawer 17 17 17 1.000 Patient with a drug not charted in drawer 56 37 46 0.3052 Patients who misseda a dose 44 7 21 0.0008 aMissed doses consists of those doses marked as “not available” on the NIMC by nursing staff Discussion • Patients who did not use POMs during their admission were at risk of medication errors – – Medication administration errors Missing doses of medications • Many medication errors, including missed doses, are avoidable • Medication drawers containing non-current, ceased, or otherwise altered medications increases the chance of medication administration errors • At SCGH, limited pharmacy operating hours restricts the availability of medications not on imprest to wards. Other factors such as pharmacy or nursing staff workload may also impact supply of medicines. • Using POMs can help reduce these barriers to supply and result in immediate availability of medication to the patient, reducing the number of missed doses likely to be received. Discussion • This is in addition to the other documented benefits both to medication safety, and to drug expenditure – – – Reduced workload of staff Improved patient care Reduction in medication wastage • These all have the potential to save time and money, and have the potential to improve the care of the patient. • Previous experience at SCGH has shown that a pre-admissions clinic pharmacist is well placed to facilitate the implementation of a POMs scheme, and that POM schemes themselves can successfully be implemented. Limitations • Impact of route and timing of admission of patient • Methodological simplifications – Inclusion/exclusion criteria – Sample population – Variables • Sample size Conclusion • This research illustrates the potential benefits of introducing a POM scheme in SCGH • More research is required to determine the implications of introducing a scheme, as well as identifying the associated barriers and facilitators • The “5 rights” of medication administration – – – – – Right drug Right patient Right dose Right route Right time References 1. 2. 3. 4. Lummis, H, Sketris, I, Veldhuyzen, S. Systematic review of the use of patients’ own medications in acute care institutions. 2006. J Clin Pharm Ther, Vol 31, 541-563. Chan, EW, Taylor, SE, Marriott, JL, Barger, B. Bringing patients’ own medications into an emergency department by ambulance: effect on prescribing accuracy when these patients are admitted to hospital. 2009. Med J Aust, Vol 191, no. 7, 374-377. Stephens, M. Hospital Pharmacy 2nd edn. London, Pharmaceutical Press; 2011. James, CR, Leong, CKY, Martin, RC, Plumridge, RJ, Patient’s own drugs and one-stop dispensing: Improving continuity of care and reducing drug expenditure. 2008. JPPR, Vol 38, no. 1, 44-46.