Delivery of CBT-I to an Underserved Population in Primary Care

Session I5-Tapas

Saturday, October 29, 2011

Implementing Cognitive Behavioral

Therapy for Insomnia in Primary

Care

Christina O. Nash, M.S. & Jacqueline D. Kloss, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Drexel University, Philadelphia

Objectives

1.

2.

3.

Briefly review literature on CBT-I in

Primary Care settings

Highlight the additional challenges via a case vignette while delivering CBT-I in light of current research

Identify areas for clinical discussion and pose research questions for future investigation

Prevalence of Insomnia in Primary Care

Widely recognized that primary care settings serve as the

“front lines” for recognizing and initiating treatment for insomnia

Many individuals with Primary Insomnia seek out help with their general practitioner(Aikens & Rouse, 2005)

50% of individuals in primary care complain of insomnia, making insomnia one of the most common complaints at general practitioner offices (Schochat, Umphress, Israel, &

Ancoli-Israel, 1999; NHLB Working Group on Insomnia)

Among a sample of 1,935 primary care patients, one third met criteria for insomnia, more than 50% reported excessive daytime sleepiness (Alattar, Harringon, Mitchell & Sloane,

2007).

Obstacles and Challenges to the Delivery of

CBT-I in PC Settings

◦ Assessment and recognition of insomnia; differential diagnosis

◦ Fast-paced setting, yet need for integrated care and collaborative relationships with behavioral health consultants

◦ Managing insomnia given a complex health picture and understanding its comorbidites (e.g., chronic health conditions)

◦ Despite efficacy of CBT and patient preference for nonpharmacological approaches, prescription medications are most commonly administered (Chesson, et al, 1999) and

CBT-I is underutilized (Morin, 1999; Espie, 1998)

◦ Health Care Providers are untrained in sleep medicine

Additional Challenges of Delivering CBT-I to

Underserved Populations

◦ Chronic health concerns in general are even more pronounced in lower

SES groups. For example, disparities documented in cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HIV, psychiatric comorbidities among underserved (Winkelby, Jatulis, Frank & Fortmann, 1992)

◦ Sleep quality is inversely related to income, unemployment, education

(Moore, Adler, Williams, Jackson, 2002; Ford and Kamerow, 1989)

◦ Individuals with lower SES as measured by education level were more likely to experience insomnia while controlling for gender, age, and ethnicity (Gellis et al., 2005) and those who have dropped out of high school demonstrated the greatest impairments due to insomnia

◦ Paucity of research on interrelationships between race, ethnicity, SES and insomnia; For example, perhaps poor sleep may account for the relationship between low SES and health disparities (Arber, Bote, &

Meadows, 2009; Cauter & Spiegel, 1999)

◦ Shift work more common among low SES, and linked to poorer sleep quality and poorer health outcomes (Cauter & Spiegel, 1999)

Research Background to CBT-I Delivery to Underserved in PC Settings

A number of studies have initiated abbreviated CBT implementation in PC settings with success (e.g, Edinger &

Sampson, 2003; Goodie et al., 2009; Hyrshko-Mullen et al,

2000; and some with primary care nurses (e.g., Espie et al,

2001; 2007; Germain et al., 2006)

However, to our knowledge, little, if any research has been conducted to examine Sleep Disorders, and specifically insomnia, among underserved community primary care patients

One study, McCrae et al. (2007) a 2-day workshop delivered by service providers (mental health counselor, a provisionally licensed counselor, and social worker) yielded significant improvement in a rural setting with elderly population

Translating CBT-I Research to Practice among Underserved Populations

How do we translate and deliver our well-established CBT-I approaches not only within a fast-paced PC setting in an abbreviated modality with care professionals who likely have limited sleep knowledge, but also to populations with complex health histories, impoverished environments, and with limited resources?

Observations from Community Health Center

Ethnicity/Race: Latino and African-American patients

Over 98% of patients are 200% below the poverty line

Potential for comorbidity

◦ 24.3% of patients met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

◦ 26% met criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

◦ 28.5% met criteria for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

◦ In a study of a sample of 288 patients conducted in 2003, 46% of patients met criteria for a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis, 14% met criteria for 2 diagnoses, and 11% met criteria for 3 diagnoses.

Of 9057 adult patients seen during the last year, 158 were diagnosed with

Psychophysiological Insomnia, 2 with Insomnia, Unspecified

◦ Over half of these patients reported symptoms of insomnia during their medical visit

◦ 120 of these patients with diagnosed insomnia are currently prescribed

Zolpidem (i.e., Ambien)

◦ Of 9057 patients, 125 were seen by Behavioral Health for screening and/or consultation

Observations from the Community

Health Center

Language barriers

Literacy

Legal status

Unemployment/Lack of a daytime routine

Patients sleeping in shelters/Homeless

Impoverished sleep environments may lead to poor sleep hygiene (e.g., noise, fear, bed availability, curtains, temperature)

Limited access to sleep education and sleep specialists

Case Vignette

Unemployed and lacks a daytime routine

History of

Domestic

Violence Diagnosed with

MDD, GAD &

PTSD

Safety Concerns in Neighborhood

Rosa

Chronic

Medical

Conditions

Did not graduate high school

One bed for four people

English as a second language

Nightmares

Treatment Implementation

Behavioral Health Consultation Delivery of CBT-I

Consult 1 “Warm-handoff” by PCP. Gathered patient history and provided psychoeducation on sleep hygiene. Sleep diaries were distributed.

Consult 2 Assess sleep diaries and implement Stimulus Control procedures. Progressive muscle relaxation strategies are introduced to help patient cope with her anxiety at bedtime.

Consult 3

Consult 4

Consult 5

Consult 6

Consult 7

Consult 8

Patient reports difficulty with Stimulus Control. Strategies are discussed and implementation is encouraged. PMR is reviewed.

Patient reports she is engaging in stimulus control and has been “sleeping better.” Sleep

Restriction is introduced and the continuation of Stimulus Control strategies is recommended.

Patient reports she has been having difficulty with Sleep Restriction and her sleep restriction schedule is reviewed.

Patient is a “no show” for her scheduled appointment.

Patient reports that she has been sleeping with less nighttime awakenings and has been falling asleep in less than 30 minutes. She is encouraged to continue utilizing CBT-I strategies.

Patient’s self-report of insomnia severity is below the threshold for insomnia. Patient wishes to discontinue behavioral health consultation at this time and promises to contact DVCH if she is having sleep difficulties again. She is encouraged to continue engaging in CBT-I.

Rosa Sleep Diary Data*

SOL

1.5 hrs

WASO

2.5 hrs

TST

4hrs Consult 1

(Baseline)

Consult 2

Consult 3

Consult 4

Consult 5

Consult 6

Consult 7

Consult 8

1.25hrs

Missing

1hr

Missing

45 min

40 min

25 min

2.5hrs

Missing

2hrs

Missing

30 min

45 min

30 min

4hrs

Missing

5.75hrs

Missing

6.25hrs

7.25 hrs

7.25 hrs

*Weekly Averages

TIB

8 hrs

7.75 hrs

Missing

7.75 hrs

Missing

6.65hrs

7.65hrs

8.70hrs

Insomnia Severity

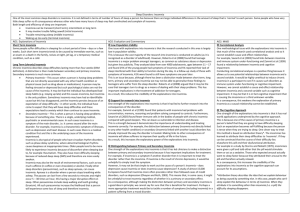

Practices and Pitfalls of CBT-I in the

Community Health Center

Method of Treatment

Delivery

“Practices” “Pitfalls”

Self-administered CBT “Cold calls” vs. “warm hand-offs” Having proper screening devices; collaborative relationships; knowledge and training; efficacy of self-help treatments?

Language barriers and Literacy

Small Group manualized brief

CBT delivered by a trained therapist

Where available, can be ideal, e.g., graduate student training model

Limited resources; rural settings; adequate training care providers, consulting BSM specialists

Individual or small group CBT delivered by a graduate psychologist

Availability of these training models

Individual, tailored CBT delivered by a clinical psychologist or

Expert CBT-I delivered by a BSM

Specialist

Limited research on efficacy of abbreviated models and limited availability

Need for supervision, BSM specialist consultation; need research on efficacy; volume outweighs staff

Cost, volume, accessibility;

Follow-up

Adapted from Espie’s Stepped Care Model (2009)

Future Research and Clinical Considerations

◦ Epidemiological studies on the links between SES and insomnia (e.g., understanding the mechanisms that link insomnia and SES, education, and health); studies on incidence, prevalence, and presentation/manifestation of insomnia

◦ Additional efficacy studies on abbreviated CBT approaches specifically with underserved populations (e.g., in rural settings, at community health centers, varied educational levels); Does one size fit all?

◦ Psychometrically sound screening and assessment measures (e.g.,

Kroenke et al, 1999; PHQ-9)

◦ How effectively can “in house” care providers deliver CBT-I? Under what conditions? How do we best access BSM specialists and provide adequate supervision and training?

◦ How do we foster collaborative relationships into an integrative care system with the use of behavioral health consultants and/or BSMtrained practitioners?

◦ Consider complex comorbidities (physical and mental health problems)

◦ Enhance decision-making about pharmacotherapy

Where do we go from here?

Stepped Care Model (Espie, 2009)

Meta-analyses demonstrated self-help tools (books, internet) to have a small to moderate effect size (Straten & Cuijpers,

2009)

Tele-health, Internet and Telephone

Consultations (e.g., Vincent& Lewycky,

2009; Bastien et al, 2004)

Group CBT-I

Implementation of Training Models

References

Alattar, M., Harrington, J.J., Mitchell, M.,, & Sloane, P. (2007). Sleep problems in primary care: a North Carolina family practice research network (NC-FP-RN) study. JABFM, 20, 365-374.

Arber, S., Bote, M. & Meadows, R. (2009). Gender and socio-economic patterning of self-reported sleep problems in

Britain. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 281-289.

Espie, C.A. (2009). “Stepped care”: a health technology solution for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy as a first line insomnia treatment. SLEEP, 32(12), 1549-1558.

Espie, C.A., Inglis, S.J., Tessier, S., & Harvey, L. (2001). The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic insomnia: implementation and evaluation of a sleep clinic in general practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 45-60.

Ford, D.E., & Kamerow, K.B. (1989). Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. Journal of the

American Medical Association, 262, 1479-1484.

Gellis, L. A., Lichstein, K. L., Scarinci, I.C., Durrence, H.H., Taylor, D.J., & Bush, A.J. (2005). Socioeconomic status and insomnia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 111-118.

Germain, A., Moul, D.E., Franzen, P.L., Miewald, J.M., Reynolds, C.F., Monk, T.H., & Buysse, D.J. (2006). Effects of a brief behavioral treatment for late-life insomnia: preliminary findings. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 403-406.

Goodie, J.L. , Isler, W.C., Hunter, C., & Peterson, A.L. (2009). Using behavioral health consultants to treat insomnia in primary care: a clinical case series. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(3), 294-304.

McCrae, C.S., McGovern, R., Lukefahr, R., & Stripling, A.M. (2007). Research evaluating brief behavioral sleep treatments for rural elderly (RESTORE): a preliminary examination of effectiveness.

Moore, J.P., Adler, N.E., Williams, D.R., & Jackson, J.S. (2002). Socioeconomic status and health. The role of sleep.

Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 337-344.

Winkelby, M.A., Jatulis, D.E., Frank, E. & Fortmann, S.P. (1992). Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Public Health, 82(6), 816-820.