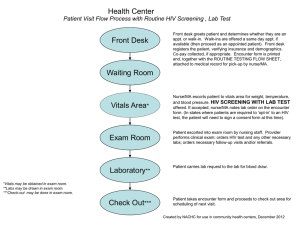

TB and HIV: from clinical practice to

public health action

Alberto Matteelli

Institute of Infectious and Tropical Diseases

University of Brescia, Italy

WHO Collaborative Centre on TB/HIV co-infection

Outline of the presentation

• Burden of HIV associated TB

• Impact of HAART on the epidemiology of HIV

associated TB

• Diagnostic standards and perspectives for HIV

associated TB

• How to treat the TB/HIV co-infection (choice of

drugs, timing, managemert of IRIS)

• Prevention of TB in HIV infected persons (early

diagnosis, IPT, ART)

• WHO recommended TB/HIV activities

How HIV influences the TB natural

history

M. tuberculosis

Relative risk for TB:

HIV neg. = < 10% per lifetime

First

Infection

HIV positive

Re-infection

(exogenous)

HIV pos. ~ 3-7 % per year

Primary

TB

Latent

TB

Reactivation

(endogenous)

Progressive

Primary TB

Post-primary TB

TB/HIV Co-infection

Overlap of two populations

Sub-Saharan African country

Infection

Infection

with HIV

with

M.

tuberculosis

Estimated HIV prevalence in new TB cases,

2009

1.1 million TB/HIV cases and 400,000 deaths

WHO, Global TB report 2010

Estimated annual TB incidence

(per 100K adults, 1999)

Estimated TB incidence vs. HIV prevalence

in high burden countries

1600

1200

800

400

HIV prevalence increases by 1%

TB incidence increases by 26/100k/yr

0

0.0

Williams B. 3rd Global TB/HIV

Working Group Meeting;

Montreux, 4-6 June 2003

0.1

0.2

0.3

HIV prevalence, adults 15-49 years

0.4

Impact of HIV on TB in Africa

4/5 of all estimated TB/HIV cases are in Africa

Notified cases per 100,000 pop. 1980-2008

TB notification rate in 20 African countries* versus HIV prevalence

in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2004

200

8

180

7

160

6

140

TB notification

rate per 100,000

population

120

5

100

4

80

3

60

% Adult HIV

prevalence

(15-49)

2

40

1

20

0

0

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

TB notification rate

HIV prevalence

• Consistently reporting each year: Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Cameroon, Comoros, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo,

Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zimbabwe

Sources: World Health Organization (2006), Global TB database; UNAIDS (2006)

4.5

TB/HIV Co-infection

Overlap of two populations

Rich European Country

Infection

Infection with

with HIV

M. tuberculosis

World Health Organization

Estimated HIV prevalence in new TB cases,

WHO European Region 2008

TB in the HIV era

• Most frequent infection associated with HIV

world-wide

• Can spread to the non-HIV population

• HIV can pull and steer the incidence of TB

Clinical case 1a

16/03/2010: B V, male, 30 years old, from Romania, working in Italy

since 4 years, is prescribed an HIV test because of genital lesions and

oral candidiasis. The test result is positive.

31/03/2010: His viro-immunological profile is as follows: CD4+ 173

(14,4%) HIV-RNA 106,000 copies. HIV treatment is prescribed:

3TC/ABC plus LPV/r.

3/05/2010: the patient develops persistent high fever and is

admitted to the ward

A chest X-ray is performed (03/05)

Abdominal CT scan (07/05)

Clinical case 1b

• TB suspect: sputum and blood samples examined – negative

microscopy

• M.tuberculosis isolated from sputum and blood on 24/05. Rapid

test for rifampicin resistance is negative.

Disseminated TB diagnosed

• 25/05: TB treatment started with RIFABUTIN 150 mg every

other day + INH/ETH/PZA; HAART is continued unchanged

• 06/06: drug sensitivity testing available: resistance to isoniazid.

The drug is removed and the TB regimen continues as planned

• The patient is fully adherent to monthly clinical visits, his

conditions improves and normalise

• 25/11: he completes TB treatment (6 months).

Key features of clinical case 1

• HAART is a significant determinant of the risk

of TB in HIV infected persons

• Smear negative pulmonary TB and

extrapulmonary TB is common

• Treatment of TB in an HIV infected person is

challenging

TB and HIV in the era of HAART

• HAART reduces the incidence of TB by approximately

80% in high and low burden countries

• TB incidence in HIV infected persons receiving effective

HAART is ~ 10 times higher than that in the background

population

• HAART may unmask TB in persons with low CD4 cell

count

• HAART may be key to control MDR epidemics among

HIV infected persons

Recurrent TB and ART in HIV-infected

patients in Rio de Janeiro

Adjusted

Relative Hazard

(95%CI)

P-value

HAART after TB Dx

0.45 (0.26-0.79)

0.005

CD4

(Timedependent)

< 200

200 – 349

350 – 499

≥ 500

1

0.46 (0.27-0.79)

0.47 (0.26-0.85)

0.32 (0.17-0.61)

0.005

0.01

< 0.001

Sex

Male

Female

1

1.03 (0.67-1.60)

0.89

1

0.85 (0.41-1.79)

0.80 (0.38-1.69)

0.26 (0.09-0.75)

0.67

0.56

0.01

Variable

Age

< 30

30-39

40-49

≥ 50

N=1042 – recurrences in 8.9%

Golub et al., AIDS 2008; 22:2527

Changes in tuberculosis (TB) incidence during 3 years of HAART in Europe and

North America with regression curve fitted. TB incidence rate is expressed as

number of cases per 1000 person-years of follow-up

Although the incidence tended to

decrease with time, it was still 150 per

100,000 PYFU during the third year

after starting HAART.

Which is 10-fold higher than in HIV

negative population

Girardi E, Clin Infect Dis 2005, 41: 1772

TB is the commonest illness among PLHIV on

ART

Incidence of tuberculosis among HIV seropositive

patients by timing after initiation of HAART

During the initial months of HAART

incident TB cases may arise as a

consequence of “unmasking” of

previously subclinical disease or the

deterioration of a pre-existing disease

due to the reconstitution of the immune

system (Lawn, 2005)

Dembele M, Int J Tub Lung Dis 2010, 14: 318

Incidence of tuberculosis among HIV seropositive

patients by timing after initiation of HAART and

site of the disease

Dembele M, Int J Tub Lung Dis 2010, 14: 318

Lessons for HIV programmes

• Start ART at early stage (CD4 350 or below)

• Increase capacity to diagnose PTB by

improved microbiological tools

• Increase capacity to diagnose EPTB

(develop algorithms)

Improving diagnostic

capacity

New(er) TB Diagnostic Tools

• LED fluorescent microscopy

• Liquid culture (e.g. MGIT)

– Sensitivity ~50-75% > L-J

• Capilia TB

– Rapid strip test that detects a TB-specific

antigen from culture

• Molecular assays

– Cepheid GeneXpert

– Hain GenoType MTBDRplus)

LED microscopy

Molecular assays

Liquid culture

Xpert MTB/RIF

Boehme et al. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1005

Among culture-positive patients, a single, direct MTB/RIF test

identified 551 of 561 patients with smear-positive TB (98.2%)

and 124 of 171 with smear-negative TB (72.5%).

The test was specific in 604 of 609 patients without

tuberculosis (99.2%).

MTB/RIF testing correctly identified 200 of 205 patients

(97.6%) with rifampin-resistant bacteria and 504 of 514

(98.1%) with rifampin-sensitive bacteria.

Proportion of TB cases detected and

time to detection

Courtesy of C Gilpin

Current understanding of Xpert TB

contribution to TB control

• Increases sensitivity of 30% compared to

miscroscopy

• Reduces time to start TB treatment

• Might have an impact on mortality

• Logistic is manageable

• Costs per TB case detected increases x 3 times but

remains cost-effective with WHO criteria (<1

GDP/capita)

• Impact on EPTB and pediatric TB under investigation

Treatment of TB in HIV

infected persons

Strategy for initiation of TB treatment

in HIV infected patients with active TB

TB treatment should be started

immediately under all

circumstances

WHO, 2010: Rapid Advice on ART

Treatment of Tuberculosis in HIV

Daily or 3 times weekly therapy only

Initial Phase

Continuation Phase*

Isoniazid

Rifampin

Pyrazinamide

Ethambutol

0

1

2*

3

4

5

months

6

7

8

9

*If culture positive at 2 months and cavitation, extend therapy to 9 months

CDC , ATS and Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines

Does 6-month therapy duration

increase the risk of relapse ?

Pooled estimate of relapse result stratified by duration of rifampin

DURATION

OF

RIFAMPIN

2 months

N. STUDIES

N.

RELAPSES

6

40/258

POOLED

RELAPSE RATE

(95% CI)

10,8 (0-25,1)

aRR

(95% CI)

6 months

12

100/730

9,8 (0-19,8)

2,4

(0,8-7,4)

> 8 months

6

20/314

3,3 (0-9,0)

1,0

(reference)

3,6

(1,1-11,7)

Khan FA, AIDS 2010 (methanalysis)

Programmatic outcomes for TB/HIV

patients are poor

WHO Global TB Report, 2009

Choice of HIV drugs

ART for HIV/tuberculosis co-infection

WHO recommendation

• Use efavirenz as the preferred non nucleoside

reverse transcriptase inhibitor in patients

starting ART while on treatment

(strong recommendation – High quality of

evidence)

WHO, 2010: Rapid Advice on ART

Efavirenz, no doubts

Advantages

Is a first line option for HIV treatment

In the most widely used first line drug in resource

limited settings

Allows for standard TB therapy

Allows for once a day therapy with minimal pill

burden (Atripla)

Clinical trials available from South Africa and

Thailand

EFV dose in TB/HIV co-infection treated

with RMP (600 versus 800 mg)

• Reduction in EFV levels:20-25%

• Clearance of EFV lower in in Afro-Americans and Hispanics

than Caucasians (impact on safety profile); body weight also

important (60 kg threshold)

• In Caucasian > 60 Kg EFV 800 mg + RIF give AUC similar to EFV

600 mg

• In Thailand and South Africa studies show effective,

pharmacological, clinical, immunological and virologic

response with conventional 600 mg EFV dose

What if efavirenz cannot be used ?

Effect of RFM on Serum Concentrations of PIs and NNRTI

PI

NNRTI

Saquinavir

80%

Nevirapine

37-58%

Ritonavir

35%

Efavirenz

13-26%

Indinavir

90%

Nelfinavir

82%

Amprenavir

81%

Lopinavir/ritonavir

75%

Atazanavir

not done

Rifabutin and HIV drugs of the PI class

Available data allows for the use of LOPINAVIR, ATAZANAVIR,

FOSAMPRENAVIR, DARUNAVIR, TIPRANAVIR always with

RITONAVIR boosting

PI blood level adequate to ensure efficacy (but few

datafrom clinical trials)

Ritonavir increases rifabutin levels significantly, requiring

a dose reduction to 150 mg every other day (DHHS)

This recommendation is derived from PK studies in

healthy volunteers

Rifabutin 150 mg every other day in

association with Lopinavir/r

• 9/10 patients with low Cmax values (<30mg/ml)

(Boulanger C, CID 2009

• 5/5 patients with low Cmax values (<45mg/ml)

Khaci H, JAC 2009)

• AUC significantly reduced compared to the

standard in 16 TB/HIV patients in South Africa.

AUC reverted by 150 mg daily during LPV/r

treatment

Naiker S, 18° ICAAR, 2011

Ryfamicin resistance

• Monoresistance described almost exclusively

in HIV infected patients

• Associated with intermittent ryfamicin use

(rifapentine, probably for low drug blood

levels)

Rifabutin low blood levels may carry a risk for

selection of rifamycin-resistant M.tuberculosis

Current dosing recommendation for rifabutin in

association with LPV/r likely to need revision

Drug Interactions: Rifampicin and

other HIV drugs

• NNRTIs

– Rifampicin decreases Etravirin exposure

“significantly”. Combination not recommended

• CCR5 Inhibitors

– Rifampicin reduces maraviroc exposure by

63%. Maraviroc doses could theoretically be

doubled but no clinical experience

• Integrase inhibitors

– Rifampicin reduces raltegravir exposure by 4060%. Raltegravir 800 mg BID suggested, but

optimal concentration range of this drug is

unknown

Drug Interactions: Rifabutin and

other HIV drugs

• NNRTIs

– No significant interactions with efavirenz and

nevirapin (but no advantage over rifampicin).

With efavirenz rifabutin dose need to be

increased to 450 mg daily

• Integrase inhibitors

– Rifabutin does not alter raltegravir exposure to

a clinically meaningful degree (Brainard DM et

al. J Clin Pharmacol 2010)

• CCR5 Inhibitors

– No clinical data

Clinical case 2a

C. L. female, 27 years old, originating from Dominican Republic. Known HIV infection

since 2005. HBV/HDV co-infections. Default from follow-up and HAART in 2007.

On 06/07/2010 admitted to the clinical ward for fever and cough since three

months, irresponsive to antibiotic therapy.

A chest X-ray is performed:

Sputum examination: AFB seen, Pneumocystis jirovecii seen

Molecular test: M.tuberculosis, no resistance markers to rifampicin

Clinical case 2b

Smear positive pulmonary TB

PCP

CD4 cell count = 27; HIV-RNA 157,000 copies

On 07/07 starts standard antituberculosis treatment with

Rimstar 4 tabs /day

On 26/07 starts HAART using TDF/FTC plus + EFV 800 mg once a

day

Discharged on 03/08 in good clinical conditions and no signs of

toxicity

Clinical case 2c

On 16/08 admission to the clinical ward for re-emergence of high fever

and cough since 3 days. A lung CT is performed.

Clinical case 2d

Adherence to TB treatment reported as optimal. Drug-sensitive TB

Concomitant opportunistic infections ruled out

Other bacterial infections not detected

CD4 cell count = 54; HIV-RNA 600 copies

On 20/08 metilprednisolone 1,5 mg / Kg /day was started

On 01/09 the patient is discharged afebrile, in good clinical

conditions, continuing TB, ARV and steroid treatment at home

Key features of clinical case 2

• Do TB/HIV patients need ART ?

• Timing of ARV in TB/HIV patients

• The risk of the immune reconstitution

syndrome (IRIS) and its relevant characteristics

• Management of the IRIS

Do TB/HIV patients

need ART ?

SAPiT Trial: Initiating ART during TB

treatment significantly increases survival

ART initiation during TB

treatment

(n = 429)

Median

67 days

ART initiation after TB

treatment (n = 213)

Median

261 days

HIV-pos with TB and

CD4+ < 500 cells/mm3

(N = 642)

Primary Endpoint: mortality rate (any cause)

Abdool Karim SS, N Engl J Med 2010; 362:697-706

Timing of Initiation of Antiretroviral Drugs

during Tuberculosis Therapy: the SAPiT trial

• HR for mortality in arm A = 0.45 (0.26

– 0.79) p=0.005 for any CD4

• HR = 0.54 for CD<200

• HR = 0.08 for CD4>200

Trial stopped by the ethical committee

Abdool Karim SS, N Engl J Med 2010; 362:697-706

Timing of ART in HIV/tuberculosis

patients

WHO recommendation

• Start ART in all HIV infected individuals with

active tuberculosis irrespective of CD4 cell

count

(strong recommendation – Low quality of evidence)

WHO, 2010: Rapid Advice on ART

Timing for ARV in TB

patients

Early (2 weeks) vs. late (8 weeks) initiation of HAART:

the CAMELIA study (Blanc et al).

Kaplan-Meier

Survival curve

CONCLUSION: Mortality was

reduced by 34% when HAART was

initiated 2 weeks vs 8 weeks after

onset of TB treatment

Timing of ART during TB therapy

Trial

ACTG 5221

STRIDE

study

(1)

Sites and

patients

Study design and

endpoint

Overall

results

Multicentre in 4

continents

(majority in

Africa).

Immediate (2 w) Vs.

early (8 w)

13.0%

Vs.16.1%

P=0.45

<500 CD4

15.5% Vs.

26.6%

Death+AIDS events

at W48

The Camelia study:

the median

TB suspect

or

of the CD4 cellc

count of

confirmed

enrolled patients

<250was

CD425 cells

One centre in

SAPiT

continuation South Africa

phase

Smear+PTB

(2)

Results in

CD4<50

P=0.02

STRIDE and SAPiT trials: for CD4>

50 there was no trend towards

decreased death/AIDS events

Early (1-4 w) Vs. late

(8-12 w)

Death+AIDS events

at W48

6.9 Vs. 7.8

/100 p-y

P=0.73

8.5 Vs. 26.3

/100 p-y

P=0.06

(1) Havlir D, et al. Abs 38, 18° CROI, Boston 2011

(2) Abdool Karim S, et al. Abs 39LB, 18° CROI, Boston 2011

ART Initiation in TB Meningitis – A

Randomized Trial in Vietnam

• Immediate – ART within 7 days after TB

initiation

• Deferred – ART initiated 2 months after TB

initiation

Immediate

Deferred

Number

127

126

Died

76

70

Survival

40%

45%

p=0.52

Torok et al. ICAAC 2009, Abstract H-1224

Timing of ART in HIV/tuberculosis

patients

WHO recommendation

• Start TB treatment first, followed by ART as

soon as possible after starting TB treatment

(strong recommendation – Moderate quality of

evidence)

WHO, 2010: Rapid Advice on ART

Optimal timing of ART among TB

patients – what is the evidence ?

• ART should be started within 2 weeks from TB

therapy in TB/HIV patients with CD4 < 50

• ART can be delayed up to the end of the

intensive phase of TB treatment in TB/HIV

patients with CD4>50

What if CD4 cannot be measured – or timely

measured ? Unclear at this time

Expected mortality should steer decision

on optimal timing of combined TB and

HIV therapy

Risk of death

while awaiting

HAART

Risk of death as a

consequence of

HAART (IRIS)

Combined HAART and treatment for

tuberculosis

Constraints

Increased rate of paradoxical reactions (IRIS)

Additive toxicity

Reduced adherence

Operational delays

Definition of IRIS

(A) Antecedent requirements

• Diagnosis of tuberculosis before starting ART

• Initial response (stabilised or improved) to tuberculosis treatment

(B) Clinical criteria

• Onset of manifestations within 3 months of ART

Plus at least one major or two minor criteria

Major criteria

1) New or enlarging lymph nodes, or similar cold abscesses, 2) New or worsening

radiological features of TB; 3) New or worsening CNS TB; 4) New or worsening

serositis

Minor criteria

1) New or worsening constitutional symptoms; 2) New or worsening respiratory

symptoms; 3) New or worsening abdominal pain

(C) Alternative explanations for

excluded if possible

clinical deterioration must be

• Failure of tuberculosis treatment because of tuberculosis drug resistance

• Poor adherence to tuberculosis treatment

• Another opportunistic infection or neoplasm

• Drug toxicity or reaction

Meintjes G et al. Lancet ID 2008; 8-516

TB IRIS

Do patients die because of IRIS ?

3·2% (0·7–9·2) of patients with

tuberculosis-associated IRIS died

Muller M, Lancet Infect Dis, 2010 10: 251 (metanalysis)

Management of IRIS

• Make certain of diagnosis

– Rule out MDR TB or new opportunistic infection

•

•

•

•

•

TB treatment should be continued

ARV treatment should be continued

Surgical drainage

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Steroids – 1.5 mg/kg prednisone

Corticosteroids and IRIS outcome

• 109 TB/HIV patients with clinical definition of IRIS in South

Africa

• Randomised, placebo controlled trial of 1.5 mg/kg/day (2

weeks) + 0.75 mg/kg/day (2 weeks)

• Cumulative # hospital days 282 Vs. 463

• Median # hospital stay 1 Vs. 3 (p=0.05)

Meintjes G, AIDS, 2010

Overlap of Adverse Reactions from Drugs

Used to Treat TB and HIV Infection

Adverse Reaction

TB Drugs

HIV Drugs

Rash

PZA, RIF, INH

NNRTIs, ABC, T/S

Hepatotoxicity

INH, RIF, PZA

PIs, NVP

Nausea

RIF, PZA, INH

RTV, AZT, APV

RBT, RIF

AZT, T/S

INH

EFV

Cytopenias

CNS

Side effects of TB treatment and HIV

infection

• Most studies demonstrate an increased rate of

side effects during TB therapy among HIV

infected persons

• In randomised trials of combined TB and HIV

therapy, toxicity was a very unlikely cause of

treatment discontinuation

ART in TB patients by Region, 2008

Region

AFR

AMR

EMR

EUR

SEAR

WPR

started on ART

30%

67%

55%

29%

35%

28%

Operationalising ART in TB patients

• Rapid HIV diagnosis

• Rapid CD4 determination (or identificatioon of

surrogate markers – BMI,Hb, clinical or

radiological signs)

• Avalability of ART (often requires referral and

loss during referral or delay)

• Instruct on how to identify and manage IRIS

• Prevention of IRIS ?

Prevention of HIV

associated TB

- Early diagnosis

- IPT

- ARV

Policies for regular TB screening

among PLWHA

• Educating health workers to early recognition

of TB symptoms in PLWHA

• At every consultation in chronic HIV care:

– Searching for signs (cough)

– Searching for symptoms (clinical examination)

• If necessary: second level investigations

(sputum microscopy, Chest X-ray)

WHO 2010 IPT/ ICF recommendations

Does the WHO algorithm for Screening HIV

Patients work ?

• Presence of symptoms – work up for

TB

– Sensitivity 79%

– Specificity 56%

• Absence of symptoms – proceed with

INH preventive therapy

– Negative predictive value 97%

Getahun H et al. Plos Med 2011; in press

Treatment of latent tuberculosis

infection

Current standard (IPT):

• Isoniazid 300 mg /daily for 6-9 months

Efficacy of IPT

compared with

placebo, in

reducing the

incidence of

active TB

Akolo C, et al. Cochrane Review, 2010

Treatment of latent tuberculosis

infection

Research perspectives:

• Shorter regimens

• Drugs with no baseline resistance

• Well tolerated

In high burden countries, where risk of

re-infection is high:

• Operationalising IPT

Efficacy of 36 vs. 6 months of INH for

HIV-infected Adults in Botswana

The BOTUSA Trial

Samandari et al., IUATLD Conference, December 2009

Can IPT increase resistance to INH ?

• There is no evidence that IPT can increase

resistance to INH provided that active disease

is ruled out

• Directly observed administration of INH is not

essential, although poor adherence will limit

the impact of IPT

Is IPT safe ?

The Botswana NTP / CDC IPT study

• Of 1,762 patients in analysis 19 (1.2%) developed

hepatitis (grade 3 or above). One patienst died. (1)

• Low rate of severe adverse events after the first six

months of IPT: 7 (0.9%) in the 6-IPT arm (placebo)

and 11 (1.3%) in the 36-IPT arm (2)

• Coadministration with ART slightly increased liver

toxicity (RR 1.59 [0.63-4.0]). Risk greater on

nevirapine (RR 2.09 [0.74 - 5.87]) than efavirenz (RR

0.96 [0.21 - 4.31]).

Clinical monitoring appropriate for safety of IPT

1. Tedia Z et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182:278

2. Samandari T, 40 IUATLD Conference, Cancún, 2009

Eligibility for IPT

In areas of high prevalence of TB (>30% infected):

All HIV infected individuals who are not affected by

active TB

In areas of lower prevalence of TB (<30% infected):

HIV infected individuals with a positive PPD test who

are not affected by active TB

Independently from CD4 cell count

36 vs. 6 months of INH for HIV-infected

Adults in Botswana -The BOTUSA Trial

Samandari et al., IUATLD Conference, December 2009

The probability of a positive TST test is

associated to the level of immune suppression

Elzi et al CID 2007

Do IGRAs help for screening of LTBI in

HIV+ subjects ?

Current evidence suggests that IGRAs perform similarly

to the tuberculin skin test at identifying HIV-infected

individuals with latent tuberculosis infection. Given

that both tests have modest predictive value and

suboptimal sensitivity, the decision to use either test

should be based on country guidelines and resource

and logistic considerations.

Cattamanchi A, et al. JAIDS 2011; 56:230-8

TB Rates by ART and INH

Treatment Status, 2003-2005

Exposure

category

Percent

Reduction

(95% CI)

Person-Years

TB Cases

Incidence Rate

(per 100 PYs)

No Rx

3,865

155

4.01 (3.40-4.69)

-

ART only

11,627

221

1.90 (1.66-2.17)

52%

(41-61%)

IPT only

395

5

1.27 (0.41-2.95)

68%

(24-90%)

Both

1,253

10

0.80 (0.38-1.47)

80%

(9-91%)

Total

17,140

391

2.28 (2.06-2.52)

Golub et al., AIDS 2007;21:1441-8

TB Rates by ARV and INH Treatment Status in

South African Adults with HIV Infection

Exposure

category

Person

TB

-years cases

Incidence rate

(per 100 PYs)

(95% CI)

Incidence rate

ratio (95% CI)

Adjusted

hazard ratio*

(95% CI)

REF

REF

Naïve

2815

200

7.1 (6.2-8.2)

HAART

only

952

44

4.6 (3.4-6.2)

0.65 (0.46-0.91) 0.36 (0.25-0.51)

INH only

427

22

5.2 (3.4-7.8)

0.73 (0.44-1.13) 0.87 (0.55-1.36)

Both

93

1

1.1 (0.2-7.6)

0.15 (0.01-0.85) 0.11 (0.02-0.78)

4287

267

6.2 (5.5-7.0)

TOTAL

* Adjusted for age, sex, CD4, prior history of TB, urban/rural

Golub et al, AIDS 2009;23:631-6

New TB screening and IPT guidelines

• TB screening and IPT in tandem

• Symptom based clinical algorithm for TB

screening developed: 4 simple questions

• INH for 6 (strong) and 36 (conditional)

months recommended

• Pregnant women, children and people

receiving ART included

• TST is not a requirement

• Should be a core function of HIV services

WHO recommended

TB/HIV collaborative

activities

Policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities

WHO recommendations 2004

A. Establish NTP-NACP collaborative mechanisms

Set up coordinating bodies for effective TB/HIV activities

at all levels

Conduct surveillance of HIV prevalence among TB cases

Carry out joint TB/HIV planning

Monitor and evaluate collaborative TB/HIV activities

B. Decrease burden of TB among PLHIV (the "3 Is")

Establish Intensified TB case finding

Introduce INH preventive therapy

Ensure TB Infection control in health care and congregate

settings

C. Decrease burden of HIV among TB patients

Provide HIV testing and counselling

Introduce HIV prevention methods

Introduce co-trimoxazole preventive therapy

Ensure HIV/AIDS care and support

Introduce ARVs

The 12 points package: what is new?

A. Establish the mechanism for integrated TB& HIV services

Set up coordinating bodies for effective TB/HIV activities

at all levels

Conduct surveillance of HIV prevalence among TB cases

Carry out joint TB/HIV planning

Conduct monitoring and evaluation

B. Decrease burden of TB among PLHIV (the "3 Is")

Establish Intensified TB case finding and ensure quality TB treatment

Introduce TB prevention with IPT or ART

Ensure TB Infection control in health care and congregate

settings

C. Decrease burden of HIV among TB patients

Provide HIV testing and counselling to TB suspects & TB patients

Introduce HIV prevention methods for TB suspects & TB patients

Provide CPT for TB patients living with HIV

Ensure HIV prevention; treatment & care for TB patients with HIV

Introduce ARVs to TB patients living with HIV

World Health Organization

TB/HIV co-infection,

WHO European Region 2008

HIV case finding among TB:

• HIV testing coverage = 79% (~ 357.000 patients)

• HIV prevalence among tested TB = 3% (~ 11.500

patients)

• Estimated HIV prevalence = 5.6% (~ 23.800 people)

• 48% of TB/HIV patients are detected

TB/HIV co-infection,

WHO European Region 2008

Management of TB/HIV co-infected patients:

• 61 % of TB/HIV patients are covered by CPT

• 9.2 % covered by IPT

• 29% of TB/HIV patients are covered by ARV

treatment

TB/HIV co-infection,

WHO European Region 2008

TB case finding among PLHIV:

• estimated TB prevalence among PLHIV = 1.7%

• screening coverage for TB = ??? (~205 000)

Challenges and response

The Health Structure

1. Extreme verticality of the TB and AIDS

programmes both in service provision and

management;

2. Lack of effective coordinating mechanisms for TB

and HIV

Challenges and response

TB/HIV/IVDU convergence

Challenges and response

TB/HIV in marginalised populations

Prisoners

Migrant people

Challenges and response

Convergence of TB/HIV and MDR-TB

Increasing convergence of drug resistant TB and HIV in

the region and the lack of understanding of the

extent of the problem.

Efforts to address drug resistant TB in the region need

to be scaled up and integrated with HIV prevention

and treatment services.

TB/HIV Working Group of the Partnership

Focus on European Region, Almaty, May 2010

Outcomes of Treatment for MDR TB in the

South African DOTS-Plus Program, 2002-2004

Outcome

HIV +

(N=327)

38.5%

HIV –/unknown

(N=875)

49.3%

P value

Failed

4.3%

11.4%

<0.001

Defaulted

21.4%

22.6%

0.65

Died

35.8%

16.7%

<0.001

Successful Rx

Farley, van der Walt, et al., IUATLD World Conference, 2007

<0.001

Thank you for your attention