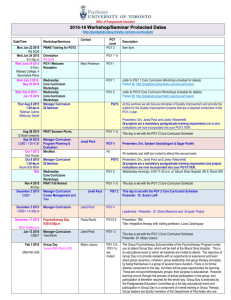

June 2011 Power Point Slide Presentation

advertisement

Communicating Diagnostic and Therapeutic Information to Patients Accounting for Lower Health Numeracy Christopher R. Carpenter, MD, MSc, Richard T. Griffey, MD, MPH, Dan Theodoro MD, June 2011 Journal Club Division of Emergency Medicine Special Thanks to our guests • Mary Politi • Kim Kaphingst Probability and Bayesian logic is confusing to everyone – not just those with low health numeracy Lay persons are not used to thinking beyond positive or negative test results or therapies recommended by their doctors. When clinicians consider test characteristics they often don’t consider these within the context of disease prevalence Classic Question: A test correctly detects disease 95% of the time (sensitivity) in people with the disease and if negative effectively clears 90% of the patients in whom the disease is absent (specificity) If disease is present in 1 out of 1000 people (prevalence) what is the probability that a randomly chosen person who tests positive really has the disease? Symptom Present Disease Status YES NO TOTAL YES 95 9990 10085 NO 5 89910 89915 TOTAL 100 99900 100000 Test characteristics: Validity (Accuracy) & Reliability Reliable, Valid, Valid and Not Valid Not Reliable Reliable Patients with possible disease Low Risk Patients Those testing positive Those with actual disease How Would You Communicate Risks & Benefits in the Emergency Department? • Need to find and appraise the evidence summary BEFORE the patient encounter • Here’s an example using tPA for acute ischemic stroke and the Wash U Journal Club archives @ http://emed.wustl.edu/em_journal_club.html http://emed.wustl.edu/emjclub_July2009_TheEvidenceSupportsThrombolyticsStroke4.5Hours.html PGY IV Critical Appraisal Calculating Benefit Pictographs http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/ From the Wash U PGY IV Critical Appraisal What About Harm? http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/ PGY I Needle Aspiration of PTX • Meta-analysis in 2007 identified only one high quality RCT upon which to base conclusions (Noppen 2002 – the PGY I article at that JC) • Noppen et al. demonstrated – No difference in immediate success rate • RR = 0.93 (95% CI 0.62-0.41) – No difference in early failure rate • RR = 1.12 (95% CI 0.59-2.13) – Lower hospitalization rates in aspiration • RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.36-0.75) Case 1: PSP Immediate Success Rate Immediate Success Rate Hospitalization Rate PGY II CT for PE • PIOPED II provided the following test characteristics for PE protocol CT Case 2: How accurate is CTA for PE? First risk stratification by Wells (prevalence): 56% low probability 38% intermediate probability 6% high probability So, we cannot PERC our patient but her Wells score is 0, so she is low probability for PE…. (sidestepping d-dimer testing…) Test characteristics: In general, when PE is present CTA detects it 83% of the time (Sensitivity) In general when CTA was negative it was correct 95% of the time (specificity) Among low prob patients though, a positive CTA indicates true disease only 58% of the time (PPV) and a negative CTA is correct 96% of the time (NPV). Diagnostic Communication Two Concepts • Test Accuracy • Disease Probability Concept #1 Test Accuracy Sensitivity = Has PE and CT shows it = Has PE and CT missed it Specificity = Does not have PE and CT did not show a PE = Does not have PE but CT showed a PE If we knew you had a PE before we tested you If we knew you did not have a PE before we tested you Concept #2 Disease Probability ? Fagan Nomogram No PE on CT Low Risk ~3.6% mean probability of PE 3.6% pre-CT and CT no PE = 0.67% In other words, if 1000 patients with these odds of having a PE had a CT that did not demonstrate a PE, about 7 of them would still have a PE 35 Fagan Nomogram PE found on CT Low Risk ~3.6% mean probability of PE 3.6% pre-CT and CT with a PE = 42.3% In other words, if 1000 patients with these odds of having a PE had a CT that demonstrated a PE, about 423 of them would actually have a PE 36 Fagan Nomogram PE found on CT High Risk ~66.7% mean probability of PE 66.7% pre-CT and CT with a PE = 97.5% In other words, if 1000 patients with these odds of having a PE had a CT that demonstrated a PE, about 975 of them would actually have a PE 38 PGY III Steroids to Prevent Recurrent Migraine • Critical appraisal provides the RR and 95% CI but not the control event rate so need to pull the original paper Control Event Rate = [22 + 10 + 8 + 18 + 20 + 43 + 20] / 353 Control Event Rate = 141/353 Control Event Rate = 0.399 PGY IV Head CT After Blunt Trauma • 30 year old male in tornado-related building collapse without objective signs/symptoms of injury: Canadian Head CT Rule Sensitivity = Has clinically important brain injury and Canadian Rule shows it = Has clinically important brain injury but Canadian Rule does not show it Specificity = Does not have a clinically important brain injury and Canadian Rule does not show one = Does not have a clinically important brain injury but Canadian Rule suggests one Fagan Nomogram Low-risk by Canadian Head CT Rule ~9% mean probability of significant injury before testing 9% pre-CT and Canadian Rule LowRisk = 0.3% In other words, if 1000 patients with these odds of having a significant intracranial injury were low risk on the Canadian Head CT rules, about 3of them would still have a significant intracranial injury 48 Fagan Nomogram High Risk by Canadian Head CT Rule ~9% mean probability of significant injury before testing 9% pre-CT and Canadian Rule HighRisk = 16% In other words, if 1000 patients with these odds of having a significant intracranial injury were non-low risk on the Canadian Head CT rules, about 160 of them would actually have a significant intracranial injury 49 What is EBM? Clinical Expertise Research Evidence Patient Preferences 51 References • Fagerlin A, et al. Making numbers matter: Present and future research in risk communication, Am J Health Behav 2007; 31: S47-S56. • Houts PS, et al. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence, Patient Educ Couns 2006: 61: 173-190. • Barry MJ et al. Reactions of potential jurors to a hypothetical malpractice suit alleging failure to perform a prostate-specific antigen test, J Law Med Ethics 2008; 36: 396-402. • Moulton B, King JS; Aligning ethics with medical decision-making: The quest for informed patient choice, J Law Med Ethics 2010; 38: 85-97. • Epstein RM, et al. Communicating evidence for participatory decision making, JAMA 2004; 291: 2359-2366. • Lipkus IM; Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: Suggested best practices and future recommendations, Med Dec Making 2007; 27: 696-713. More References • Fagerlin A, et al. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: Is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making 2005; 25: 398-405. • Fagerlin A, et al. Measuring numeracy without a math test: Development of the subjective numeracy scale, Med Dec Making 2007; 27: 672-680. • Lipkus IM, et al. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples, Med Decis Making 2001; 21: 37-44. • Woloshin S, et al. Assessing values for health: Numeracy matters, Med Decis Making 2001; 21: 382-390. • Politi MC, et al. Communicating the uncertainties of harms and benefits of medical interventions, Med Decis Making 2007; 27: 681-695. • Hoffrage U, et al. Representation facilitates reasoning: what natural frequencies are and what they are not, Cognition 2002; 84: 343-352. And More References • Hoffrage U, Gigerenzer G; Using natural frequencies to improve diagnostic inferences, Acad Med 1998; 73: 538-540. • Loong TW; Understanding sensitivity and specificity with the right side of the brain, BMJ 2003; 327: 716-719. • Windish DM et al. Medicine residents’ understanding of the biostatistics and results in the medical literature, JAMA 2007; 298: 1010-1022. • Horowitz HW; The interpreter of facts, JAMA 2008; 299: 497-498. • Halvorsen PA, et al. Different ways to describe the benefits of risk-reducing treatments: a randomized trial, Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 848-856. • Woloshin S, et al. The effectiveness of a primer to help people understand risk: two randomized trials in distinct populations, Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 256-265. • Shalowitz DI, Wolf MS; Shared decision-making and the lower literate patient, J Law Med Ethics 2004; 32: 759-764. Textbook References • Kassirer JP, Kopelman RI; Learning Clinical Reasoning, Williams and Wilkins 1991. • Newman TB, Kohn MA; Evidence-Based Diagnosis, Cambridge University Press 2009. • Gigerenzer G, Calculated Risks: How to Know When Numbers Deceive You, Simon and Shuster 2002.