Evidence-based medicine

advertisement

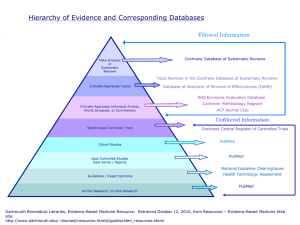

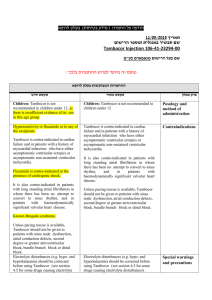

Introduction to EvidenceBased Medicine: Part 1 Prof. Dr. R. Erol Sezer Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of the best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” http://ebm.mcmaster.ca/documents/ how to teach ebcp workshop brochure 2009.pdf “EBM requires the integration of the best research evidence with our clinical expertise and our patient’s unique values and circumstances.” Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS ,Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it. Fourth Edition 2011. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. Evidence means grounds for belief . By best evidence we mean research findings from clinically relevant research, especially from patientcentered (or patient oriented) research. (Not from disease oriented research) The flecainide story: Glasziou P, Del Mar C, Salisbury J. Evidence-based Practice Workbook. BMJ Books, Blackwell Publishing, 2007. “..In 1979 the developer of the defibrilator, Bernard Lown, pointed out in an address to the American College of Cardiology that one of the biggest causes of death was heart attack, particularly among young and Middle-aged men (20-64 year olds). People had a heart attack, developed arrythmia, and died from arrythmia.. He suggested that a safe and long acting antiarrythmic drug that protects against ventricular fibrilation would save millions of lives.” In fact in an article published in 1977 ventricular premature depolarizations were reported to be a risk factor for sudden death and nonsudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction. Ruberman et al. Ventricular premature beats and mortality after myocardial infarction. NEJM 1977;297:750-757 In response to the challenge expressed by Albert Lown, a paper was published in 1981 in the NEJM introducing a new drug called flecainide. (Anderson JL. Oral flecainide acetate for treatment of ventricular arrhythmia. NEJM 1981;305:473-477) The paper described a study in which patients who had just had heart attack were randomly assigned to groups to receive either a placebo or flecainide and were then switched from one group to the other (a crossover trial). ..The researchers counted the number of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) as a measure of arrythmia.” The results can be seen in the following figure: PVCs/12 hours Effects of flecainide and placebo on number of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) among nine patients who had just had heart attack (Each line represents one patient) Anderson JL. Oral flecainide acetate for treatment of ventricular arrhythmia. NEJM 1981;305:473-477 The patients on flecainide had fewer PVCs than patients on placebo. When the flecainide patients were ‘crossed over’ to the placebo treatment, the PVCs increased again. Conclusion was straightforward: flecainide reduces arrythmias (PVCs). Therefore people who have had heart attack should be given flecainide. After the results were published flecainide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and became fairly standard treatment for heart attack. Several years later The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) designed to test whether the suppression of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic ventricular arrhythmia with the drug flecainide after myocardial infarction would reduce mortality started to recruit patients in june 1987. It was a multicenter , randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial (or briefly a randomized control trial – RCT) Recruitment of study subjects (inclusion and exclusion criteria ) was described in the study protocol: “..patients were eligible for enrolment six days to two years after myocardial infarction if they had an average of six or more ventricular pramature depolarizations per hour on ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring of at least 18 hours duration……” All of the following rules for a valid RCT study were implemented 1. Was the assignment of patients to treatments randomised? 2. Was the randomization concealed ? 3. Were the groups similar at the start of the trial? 4. Was follow-up of patiens sufficiently long and complete? 5.Were all patients analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? 6.Were patients, clinicians and study personnel kept blind to treatment? 7.Were the groups treated equally, apart from the experimental therapy? Recruitment was planned to last three years from June 1987 to June 1990 “ However, in April 1989 the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) — sometimes called “Data and Safety Monitoring Board” (DSMB) terminated the flecainide trial. (An independent group of experts who monitor patient safety and treatment efficacy data while a clinical trial is ongoing.There are typically three reasons a DMC might recommend termination of the study: safety concerns, outstanding benefit, and futility.) Because: % Alive Cardiac arrhythmia suppression trial Gün Echt DS et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. Cardiac Arrhythimia Supression Trial. NEJM 1991;324:781-788. Over the 18 months following treatment, more than 10% of people who were given flecainide died, which was almost triple the rate of deaths among the placebo group. A book tells this story in detail. “A deadly Medicine” by Moore TJ -1995, Simon and Schuster, Newyork Despite a perfectly good mechanism for the usefulness of flecainide (it reduces arrhythmias), the drug was clearly toxic and, overall, did more harm than good. By the time results of this trial were published, at least 100 000 such patients had been taking this drug. We can not rely on pathophysiologic (mechanistic) reasoning and evidence. This type of evidence is also described as disease oriented evidence (DOEs). Best evidence regarding interventions comes from randomized controlled trials focusing on patient-centered (or patient oriented) outcomes such as mortality, quality of life , survival, cure. This type of evidence is also described patient oriented evidence that matters (POEMs) It was showed that many widely used therapies that had been adopted based on lower form of evidence (coming from expert opinion and/or pathophysiologic reasoning) proved to be useless when subjected to randomized trials. Jeremy howick states in his book (The philosophy of evidence-based medicine. 2011, Blackwell Publishing Ltd) “The EBM philosophy of evidence is best expressed in the EBM hierarchies… The idea behind the many different hierarchies can be summed up quite simply with three central claims: 1. Randomized trials or systematic reviews of many randomized trials generally offer stronger evidential support than observational studies. 2. Comparative clinical studies in general including both randomized clinical trials and observational studies offer stronger evidential support than mechanistic reasoning (pathophysiologic rationale) from more basic sciences. 3. Comparative clinical studies in general including both randomized clinical trials and observational studies offer stronger evidential support than expert clinical judgement” “..By clinical expertise we mean the ability to use our clinical skills and past experience to rapidly identify each patient’s unique health state and diagnosis, their individual risks and benefits of potential interventions, and personal values and expectations.” Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS ,Haynes RB. Evidencebased medicine: how to practice and teach it. Fourth Edition 2011. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. “…By patient values we mean the unique preferences, concerns and expectations each patient brings to a clinical encounter and which must be integrated into clinical decisions if they are to serve the patient.” Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS ,Haynes RB. Evidencebased medicine: how to practice and teach it. Fourth Edition 2011. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. “…By patient circumstances we mean their individual clinical state and the clinical setting.” Straus SE, Glasziou P, Richardson WS ,Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it. Fourth Edition 2011. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. The complete practice of EBM comprises five steps: Step 1-Formulating an answerable clinical question: Converting the need for information (about prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, therapy, causation) into an answerable question. Step 2- Searching the available evidence : Tracking down the best evidence with which to answer that question. Step 3: Critically appraising that evidence for its validity (closeness to the truth), impact (size of the effect), and applicability (usefulness in our clinical practice) Step 4: Integrating the critical appraisal with our clinical expertise and with our patient’s unique biology, values and circumstances. Step 5: Evaluating our effectiveness and efficiency in executing steps 1-4 and seeking ways to improve them both for the next time. EBM practice begins and ends with patients. It is a new paradigm to provide the best possible care to patients It is a new paradigm for lifelong learning in medicine Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is also called evidence-based health care (EBHC) or evidence-based practice (EBP) to broaden its application from medicine to the allied health professions. “Evidence-based health service” is the practice of evidence-based medicine at the organizational or institutional level. Step 1 Formulating a clinical question Example 1: Ayşe Hanım is a 56 year old woman and quite often goes to Ankara by bus to visit her university student son. It takes 7 hours for her to get to Ankara. She tends to get swollen legs on this trips and is worried about her risk of developing deep vein thrombosis. Because she has read quite a bit about this in newspapers lately, she asks you if she should wear elastic stockings on her next trip to reduce her risk of this. A clinical question you have in mind during a patient encounter can be divided into four components. Dissecting the question into its component parts and restructuring it so that it is easy to find the answers is an essential first step in EBP. This restructured problem is called a PICO (pee-co) question. Population and clinical Problem: P Intervention (or indicator or Index test): I Comparator/Control C Outcome: O Population and clinical problem” or P shows who the relevant people are in relation to the clinical problem that you have in mind. Intervention (or indicator or index test) shows the management strategy or exposure or test you want to find out Intervention: A procedure (such as drug treatment, surgery, diet) Indicator: exposure to an harmful agent or a factor that might affect a health outcome Index test: A diagnostic test or a screening test Comparator: This shows an alternative or control strategy, exposure or test foe comparison with the one you are interested in. Outcome: This shows what you are most concerned about happening (or stopping happening AND/OR what the patient is most concerned about. The “6S” hierarchy of organization of pre-appraised evidence 1. Systems: Computerized decision support 2. Summaries: Evidence-based digital textbooks (eg, UpToDate, ACP Med, CE, PIER, UTD, Dynamed) 3. Synopses of syntheses: Evidence-based journal abstracts (eg, ACPJC, EBM, EBN, DARE) 4. Syntheses: Systematic reviews (eg, ACPJC, EvidenceUpdates, Cochrane) 5. Synopses of studies: Evidence-based journal abstracts 6. Studies: Original journal articles (eg, ACPJC,EvidenceUpdates) Evidence-based digital textbooks: • • • • • • • • ACP Med: American College Of Physicians Medicine CE: Clinical Evidence PIER: Physicians Education and Information Resource UpToDate ACP Journal Club Database of Reviews of Evidence Evidence-Based Medicine Evidence-Based Nursing