Class 5 - Physics at Oregon State University

advertisement

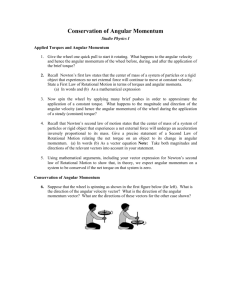

Angular Momentum The mass of an object (m) is the measure of its resistance to translational acceleration. The moment of inertia of an object (I) is the measure of its resistance to angular acceleration. How does quantifying I help us to understand objects in rotational motion? (How did quantifying m help us to understand objects in translational motion?) 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 1 Another Fundamental Consistency in the Universe: The Conservation of Angular Momentum The whole point of defining I properly is to understand the “persistence” of angular motion—just as we understand the “persistence” of translational motion: Momentum. Accordingly, we write angular momentum as the product of an angular velocity and rotational inertia: L = I* And like its linear counterpart, angular momentum is apparently a property of all matter—every object (anything with mass) in the universe. And, again, like linear momentum, so far as we have observed: The total quantity of this property, angular momentum, in the universe is constant. In other words, it cannot be either created or destroyed. It can only be transferred between objects. *at least for objects symmetric about a rotational axis. 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 2 Here are some of the direct analogies between (linear) translational and rotational motion: Quantity or Principle Linear Rotation Displacement x Velocity v Acceleration a Inertia (resistance to acceleration) mass (m) moment of inertia (I) Momentum P = mv L = I 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 3 Thus we can argue the same case as with linear momentum: In an isolated system (any set of objects unaffected by any exchanges of momentum except with one another), L = 0. That is, Li = Lf. Q: An ice-skater is standing upright and spinning in place on the ice, with her arms outstretched and no friction to slow her rotation. Then she draws her arms in toward her body—toward her axis of rotation. What must happen? A: There is no external influence on her rotation, so L = 0. But by drawing in her arms, she is reducing her moment of inertia for this rotation: There is more mass (her arms) closer to the axis of rotation. So if L does not change, but I has decreased, must increase. 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 4 Two buckets spin around in a horizontal circle on frictionless bearings. When it begins to rain (no wind, with vertical rainfall) into the buckets… A. The buckets speed up because the gravitational potential energy of the rain is transformed into kinetic energy. B. The buckets continue to rotate at constant , because the rain falls vertically but the buckets move horizontally. C. The buckets slow down, because the angular momentum of the bucket + rain system is conserved. D. The buckets continue to rotate at constant , because the total Emech of the bucket + rain system is conserved. E. None of the above. 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 5 (Similar to HW2, problem 4b) A figure skater spins in place on frictionless ice. At first, with her arms outstretched, her angular velocity is 10.0 rad/s. Then she draws in her arms, which decreases her moment of inertia about the axis of rotation by 20%. What is her new angular velocity? 1. 7.50 rad/s 2. 8.00 rad/s 3. 12.0 rad/s 4. 12.5 rad/s 5. None of the above. 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 6 Can collisions and explosions happen with rotating objects? Yes. Suppose two objects, each able to spin about the same axis, collide and stick together (say, the two clutch plates in a car’s transmission system). Or suppose a single mass drops onto a rotating carousel and comes to rest at a point some distance from the hub. Those are cases of “two objects becoming one”—a collision —and at least one of the objects has rotational motion and therefore angular momentum. But the new combined object has a different I and therefore a different . What if a child begins to walk around a rotating carousel? This is “one object becoming two”—an explosion—and each object now has its own I and around the axis. 1/14/15 Oregon State University PH 212, Class #5 7