yuval9

advertisement

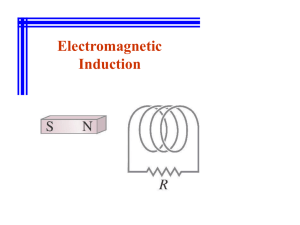

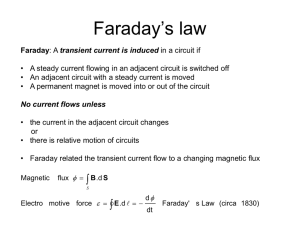

Ben Gurion University of the Negev www.bgu.ac.il/atomchip Physics 2B for Materials and Structural Engineering Lecturer: Daniel Rohrlich Teaching Assistants: Oren Rosenblatt, Shay Inbar Week 8. Faraday’s law – Magnetism in matter • Faraday’s law of induction • Lenz’s law • “motional emf” • towards Maxwell’s equations Source: Halliday, Resnick and Krane, 5th Edition, Chaps. 34-35. Faraday’s law of induction In 1831, Michael Faraday (in England) and Joseph Henry (in the U.S.) independently discovered that a changing magnetic flux ΦB through a conducting circuit induces a current! Source: UCSC Faraday’s law of induction In 1831, Michael Faraday (in England) and Joseph Henry (in the U.S.) independently discovered that a changing magnetic flux ΦB through a conducting circuit induces a current! The sign of the current depends on the sign of dΦB/dt. Faraday’s law of induction In 1831, Michael Faraday (in England) and Joseph Henry (in the U.S.) independently discovered that a changing magnetic flux ΦB through a conducting circuit induces a current! The sign of the current depends on the sign of dΦB/dt. Faraday’s law of induction In 1831, Michael Faraday (in England) and Joseph Henry (in the U.S.) independently discovered that a changing magnetic flux ΦB through a conducting circuit induces a current! The sign of the current depends on the sign of dΦB/dt. Faraday’s law of induction In fact, the induced “emf” E is directly proportional to dΦB/dt. What is an “emf”? It is short for “electromotive force”, which is not the correct term because an “emf” is not a force. It has units of volts. An “emf” is like a potential, but here, evidently, the concept of a potential doesn’t work. Physically, an “emf” is an electric field that is created in a conductor. A better version of Faraday’s law is d B E(r) dr dt . Faraday’s law of induction Example 1: A conducting circuit wound 200 times has a total resistance of 2.0 Ω. Each winding is a square of side 18 cm. A uniform magnetic field B is directed perpendicular to the plane of the circuit. If the field changes linearly from 0.00 to 0.50 T in 0.80 s, what is the magnitude of (a) the induced “emf” E in the circuit (b) the induced electric field E, and (c) the induced current I? Faraday’s law of induction Example 1: A conducting circuit wound 200 times has a total resistance of 2.0 Ω. Each winding is a square of side 18 cm. A uniform magnetic field B is directed perpendicular to the plane of the circuit. If the field changes linearly from 0.00 to 0.50 T in 0.80 s, what is the magnitude of (a) the induced “emf” E in the circuit (b) the induced electric field E, and (c) the induced current I? Answer: (a) We calculate dΦB/dt = (dB/dt) (200) (area)= (0.625T/s) (200) (18 cm)2 = 4.05 T · m2/s = 4.05 W/s = 4.05 V = E. (The weber W = T · m2 is the MKS/SI unit of magnetic flux, and since T = N /(m/s) · C = V · s/m2, we have W/s = V.) Faraday’s law of induction Example 1: A conducting circuit wound 200 times has a total resistance of 2.0 Ω. Each winding is a square of side 18 cm. A uniform magnetic field B is directed perpendicular to the plane of the circuit. If the field changes linearly from 0.00 to 0.50 T in 0.80 s, what is the magnitude of (a) the induced “emf” E in the circuit (b) the induced electric field E, and (c) the induced current I? Answer: (b) The total length of the wire is (200) (4) (0.18 m) = 144 m. From the “emf” = 4.05 V we infer E = 4.05 V/144 m = 0.028 V/m. (c) The current is I = V/R = 4.05 V/2.0 Ω = 2.0 A. Faraday’s law of induction Example 2: Two bulbs are connected to opposite sides of a loop of wire, as shown. A decreasing magnetic field (confined to the circular area shown) induces an “emf” in the loop that causes the two bulbs to light. What happens to the brightness of each bulb when the switch is closed? Bulb 1 Bulb 2 B Faraday’s law of induction Answer: Bulb 2 stops glowing, since it is shorted out, and Bulb 1 glows brighter, since it is the only resistance in the circuit. Bulb 1 Bulb 2 B Faraday’s law of induction Example 3: The conducting bar at the right is pulled right with force Fapp at speed v. The resistance R is the only resistance in the circuit. The magnetic field B is constant and perpendicular to the plane of the circuit. What is the current I and what is the power applied? v L R FB Fapp I x Faraday’s law of induction Answer: The flux ΦB is BLx, so dΦB/dt = BLv. Thus the current is I = (BLv)/R. The force FB equals BIL so the power applied is FBv = BILv =I2R, i.e. the power applied is the power lost in “Joule heating” of the resistor. v L R FB Fapp I x Lenz’s law Let’s see if we can understand not only the magnitude but also the sign of the current induced by a changing magnetic field. The figure below is taken from Example 3 with one change: The direction of the induced current I is reversed. v L R FB Fapp I x Lenz’s law But if the direction of I is reversed, then so is the direction of FB; then the bar accelerates to the right, v increases, I increases, FB increases further without limit, and energy is not conserved. v L FB Fapp R I x Lenz’s law But if the direction of I is reversed, then so is the direction of FB; then the bar accelerates to the right, v increases, I increases, FB increases further without limit, and energy is not conserved. v L FB R I x Lenz’s law But if the direction of I is reversed, then so is the direction of FB; then the bar accelerates to the right, v increases, I increases, FB increases further without limit, and energy is not conserved. Consider also the direction of the magnetic flux generated by I. v L FB R I x Lenz’s law These considerations lead us to conclude, with H. Lenz, that the current induced in a loop by a changing magnetic flux must generate an opposite magnetic flux through the loop. v L R FB Fapp I x Lenz’s law Example 2: The galvanometer indicates a clockwise current (seen from above). The south pole of the magnet is down. Is the hand inserting or withdrawing the magnet? Lenz’s law Example 2: The galvanometer indicates a clockwise current (seen from above). The south pole of the magnet is down. Is the hand inserting or withdrawing the magnet? Answer: A clockwise current implies a downward magnetic flux. So the flux due to the magnet must be increasing. The flux from the south pole of a magnet increases when the magnet is inserted. S N Lenz’s law Example 3: A cylindrical magnet of mass M fits neatly into a very long metal tube with thin steel walls, and slides down it without friction. The radius of the magnet is r and the strength of the magnetic field at its top and bottom is B. The magnet begins falling with acceleration g. (a) Show that the speed of the magnet approaches a limiting value v. (b) What is the rate of heat dissipation in the tube, in terms of v and the other data? Lenz’s law Answer: (a) The falling magnet induces a circulating current in the tube. By Lenz’s law, the magnetic field of this current opposes the falling magnet, until the magnetic force exactly balances the force of gravity on the magnet, which falls with constant speed v. (b) Gravity, the only external force on this system, does work at the rate Mgv. By energy conservation, this must be the rate of heat dissipation in the tube. “Motional emf” A so-called “motional emf” arises when a conductor moves in a constant magnetic field. Thus the moving bar (below) is an example of a “motional emf”. But a “motional emf” can arise also from the Lorentz force without any magnetic induction. v L R FB Fapp I x “Motional emf” Example 1: A conducting strip of length L moves sideways with constant velocity v through a constant B pointing out of the screen. What is the potential difference ΔV between the two ends of the strip? B ++ L v FB – – “Motional emf” Answer: At equilibrium, the force on charges anywhere in the strip must vanish, i.e. E = vB as in the Hall effect. The potential difference is then ΔV = EL = vBL. B ++ L v FB – – “Motional emf” Example 2: A conducting strip of length L rotates around a point O with constant angular frequency ω, in a constant B pointing out of the screen. What is the potential difference ΔV between the two ends of the strip? v r dr L O “Motional emf” Answer: An electron in an element dr of the conducting strip is subject to a centripetal magnetic force evB which must be balanced by an electric force eE = evB = eωrB. (Note v is not uniform along the strip.) Integrating E(r)dr along the strip, we obtain V L 0 L 0 E(r )dr B rdr BL2 /2 . v r dr L O Towards Maxwell’s equations The set of four fundamental equations for E and B, E dA 0 q B dr 0 I B dA 0 , d E dr B dt (Gauss’s law) (Faraday’s law) (Ampère’s law) together with the Lorentz force law FEM = q (E + v × B), sum up everything we have learned so far about electromagnetism! Towards Maxwell’s equations The set of four fundamental equations for E and B, E dA 0 q B dr 0 I B dA 0 , d E dr B dt (Gauss’s law) (Faraday’s law) (Ampère’s law) are similar to the famous equations named after J. C. Maxwell – “Maxwell’s equations” – describing all of electromagnetism. But they are not yet Maxwell’s equations! Towards Maxwell’s equations The set of four fundamental equations for E and B, E dA 0 q B dr 0 I B dA 0 , d E dr B dt (Gauss’s law) (Faraday’s law) (Ampère’s law) include one equation with an error that Maxwell discovered and corrected. What is the error?