digit

advertisement

Compiler Construction

3주 강의

Lexical Analysis

Lexical Analysis

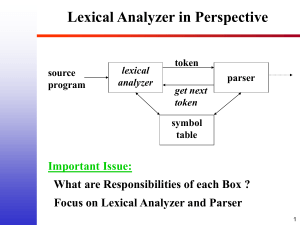

Source

Program

Lexical

Analyzer

token

Parser

get next token

Symbol

Table

“get next token” is a command sent from the

parser to the lexical analyzer.

On receipt of the command, the lexical

analyzer scans the input until it determines

the next token, and returns it.

Other jobs of the lexical analyzer

We also want the lexer to

Strip out comments and white space from

the source code.

Correlate parser errors with the source

code location (the parser doesn’t know

what line of the file it’s at, but the lexer

does)

Tokens, patterns, and lexemes

A TOKEN is a set of strings over the source

alphabet.

A PATTERN is a rule that describes that set.

A LEXEME is a sequence of characters

matching that pattern.

E.g. in Pascal, for the statement

const pi = 3.1416;

The substring pi is a lexeme for the token

identifier

Example tokens, lexemes, patterns

Token

Sample Lexemes

Informal description of pattern

if

if

if

While

While

while

Relation

<, <=, = , <>, > , >=

< or <= or = or <> or > or >=

Id

count, sun, i, j, pi, D2

Letter followed by letters and digits

Num

0, 12, 3.1416, 6.02E23

Any numeric constant

literal

“please enter input values”

Any characters between “ and ”

Tokens

Together, the complete set of tokens form the set of

terminal symbols used in the grammar for the parser.

In most languages, the tokens fall into these

categories:

Keywords

Operators

Identifiers

Constants

Literal strings

Punctuation

Usually the token is represented as an integer.

The lexer and parser just agree on which integers are

used for each token.

Token attributes

If there is more than one lexeme for a token,

we have to save additional information about

the token.

Example: the token number matches lexemes

10 and 20.

Code generation needs the actual number,

not just the token.

With each token, we associate ATTRIBUTES.

Normally just a pointer into the symbol table.

Example attributes

For C source code

E=M*C*C

We have token/attribute pairs

<ID, ptr to symbol table

<Assign_op, NULL>

<ID, ptr to symbol table

<Mult_op, NULL>

<ID, ptr to symbol table

<Mult_op, NULL>

<ID, ptr to symbol table

entry for E>

entry for M>

entry for C>

entry for C>

Lexical errors

When errors occur, we could just crash

It is better to print an error message then

continue.

Possible techniques to continue on error:

Delete a character

Insert a missing character

Replace an incorrect character by a correct

character

Transpose adjacent characters

Token specification

REGULAR EXPRESSIONS (REs) are the most

common notation for pattern specification.

Every pattern specifies a set of strings, so an RE

names a set of strings.

Definitions:

The ALPHABET (often written ∑) is the set of legal input

symbols

A STRING over some alphabet ∑ is a finite sequence of

symbols from ∑

The LENGTH of string s is written |s|

The EMPTY STRING is a special 0-length string denoted ε

More definitions: strings and

substrings

A PREFIX of s is formed by removing 0 or

more trailing symbols of s

A SUFFIX of s is formed by removing 0 or

more leading symbols of s

A SUBSTRING of s is formed by deleting a

prefix and a suffix from s

A PROPER prefix, suffix, or substring is a

nonempty string x that is, respectively, a

prefix, suffix, or substring of s but with x ≠ s.

More definitions

A LANGUAGE is a set of strings over a fixed

alphabet ∑.

Example languages:

Ø (the empty set)

{ε}

{ a, aa, aaa, aaaa }

The CONCATENATION of two strings x and y

is written xy

String EXPONENTIATION is written si, where

s0 = ε and si = si-1s for i>0.

Operations on languages

We often want to perform operations on sets of strings

(languages). The important ones are:

The UNION of L and M:

L ∪ M = { s | s is in L OR s is in M }

The CONCATENATION of L and M:

LM = { st | s is in L and t is in M }

The KLEENE CLOSURE of L:

L* { i 0 Li }

The POSITIVE CLOSURE of L:

L { i 1 Li }

Regular expressions

REs let us precisely define a set of

strings.

For C identifiers, we might use

( letter | _ ) ( letter | digit | _ )*

Parentheses are for grouping, | means

“OR”, and * means Kleene closure.

Every RE defines a language L(r).

Regular expressions

Here are the rules for writing REs over an

alphabet ∑ :

1.

2.

3.

ε is an RE denoting { ε }, the language

containing only the empty string.

If a is in ∑, then a is a RE denoting { a }.

If r and s are REs denoting L(r) and L(s), then

1.

2.

3.

4.

(r)|(s) is a RE denoting L(r) ∪ L(s)

(r)(s) is a RE denoting L(r) L(s)

(r)* is a RE denoting (L(r))*

(r) is a RE denoting L(r)

Additional conventions

To avoid too many parentheses, we

assume:

1.

2.

3.

* has the highest precedence, and is left

associative.

Concatenation has the 2nd highest

precedence, and is left associative.

| has the lowest precedence and is left

associative.

Example REs

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

a|b

(a|b)(a|b)

a*

(a | b )*

a | a*b

Equivalence of REs

Axiom

Description

r|s = s|r

| is commutative

r|(s|t) = (r|s)t

| is associative

(rs)t = r(st)

Concatenation is associative

r(s|t) = rs|rt

(s|t)r = sr|tr

Concatenation distributes over |

εr=r

rε=r

ε Is the identity element for concatenation

r* = (r| ε)*

Relation between * and ε

r** = r*

*

is idempotent

Regular definitions

To make our REs simpler, we can give

names to subexpressions. A REGULAR

DEFINITION is a sequence

d1 -> r1

d2 -> r2

…

dn -> rn

Regular definitions

Example for identifiers in C:

letter -> A | B | … | Z | a | b | … | z

digit -> 0 | 1 | … | 9

id -> ( letter | _ ) ( letter | digit | _ )*

Example for numbers in Pascal:

digit -> 0 | 1 | … | 9

digits -> digit digit*

optional_fraction -> . digits | ε

optional_exponent -> ( E ( + | - | ε ) digits ) | ε

num -> digits optional_fraction optional_exponent

Notational shorthand

To simplify out REs, we can use a few

shortcuts:

1. + means “one or more instances of”

a+ (ab)+

2. ? means “zero or one instance of”

Optional_fraction -> ( . digits ) ?

3. [] creates a character class

[A-Za-z][A-Za-z0-9]*

You can prove that these shortcuts do not

increase the representational power of REs,

but they are convenient.

Token recognition

We now know how to specify the tokens for

our language. But how do we write a program

to recognize them?

if

then

else

relop

id

num

->

->

->

->

->

->

if

then

else

< | <= | = | <> | > | >=

letter ( letter | digit )*

digit ( . digit )? ( E (+|-)? digit )?

Token recognition

We also want to strip whitespace, so we

need definitions

delim

ws

->

->

blank | tab | newline

delim+

Attribute values

Regular Expression

Token

Attribute value

ws

-

-

if

if

-

then

then

-

else

else

-

id

id

ptr to sym table entry

num

num

ptr to sym table entry

<

relop

LT

<=

relop

LE

=

relop

EQ

<>

relop

NE

>

relop

GT

>=

relop

GE

Transition diagrams

Transition diagrams are also called finite automata.

We have a collection of STATES drawn as nodes in a graph.

TRANSITIONS between states are represented by directed

edges in the graph.

Each transition leaving a state s is labeled with a set of input

characters that can occur after state s.

For now, the transitions must be DETERMINISTIC.

Each transition diagram has a single START state and a set of

TERMINAL STATES.

The label OTHER on an edge indicates all possible inputs not

handled by the other transitions.

Usually, when we recognize OTHER, we need to put it back in

the source stream since it is part of the next token. This action

is denoted with a * next to the corresponding state.

Automated lexical analyzer

generation

Next time we discuss Lex and how it

does its job:

Given a set of regular expressions,

produce C code to recognize the tokens.

Lexical Analysis

Lexical Analysis Example

Lexical Analysis With Lex

Lexical analysis with Lex

Lex source program format

The Lex program has three sections,

separated by %%:

declarations

%%

transition rules

%%

auxiliary code

Declarations section

Code between %{ and }% is inserted directly into the lex.yy.c.

Should contain:

Manifest constants (#define for each token)

Global variables, function declarations, typedefs

Outside %{ and }%, REGULAR DEFINITIONS are declared.

Examples:

delim

ws

letter

[ \t\n]

{delim}+

[A-Za-z]

Each definition is a name

followed by a pattern.

Declared names can be

used in later patterns, if

surrounded by { }.

Translation rules section

Translation rules take the form

p1 { action1 }

p2 { action2 }

……

pn { actionn }

Where pi is a regular expression and actioni is a C program

fragment to be executed whenever pi is recognized in the input

stream.

In regular expressions, references to regular definitions must be

enclosed in {} to distinguish them from the corresponding

character sequences.

Auxiliary procedures

Arbitrary C code can be placed in this

section, e.g. functions to manipulate

the symbol table.

Special characters

Some characters have special meaning to Lex.

‘.’ in a RE stands for ANY character

‘*’ stands for Kleene closure

‘+’ stands for positive closure

‘?’ stands for 0-or-1 instance of

‘-’ produces a character range (e.g. in [A-Z])

When you want to use these characters in a RE, they must be

“escaped”

e.g. in RE {digit}+(\.{digit}+)? ‘.’ is escaped with ‘\’

Lex interface to yacc

The yacc parser calls a function yylex() produced by

lex.

yylex() returns the next token it finds in the input

stream.

yacc expects the token’s attribute, if any, to be

returned via the global variable yylval.

The declaration of yylval is up to you (the compiler

writer). In our example, we use a union, since we

have a few different kinds of attributes.

Lookahead in Lex

Sometimes, we don’t know until looking ahead several

characters what the next token is. Recognition of the

DO keyword in Fortran is a famous example.

DO5I=1.25 assigns the value 1.25 to DO5I

DO5I=1,25 is a DO loop

Lex handles long-term lookahead with r1/r2:

DO/({letter}|{digit})*=({letter}|{digit})*,

Recognize keyword DO

(if it’s followed by letters & digits, ‘=’,

more letters & digits, followed by a ‘,’)

Finite Automata for Lexical Analysis

Automatic lexical analyzer generation

How do Lex and similar tools do their job?

Lex translates regular expressions into transition

diagrams.

Then it translates the transition diagrams into C

code to recognize tokens in the input stream.

There are many possible algorithms.

The simplest algorithm is RE -> NFA -> DFA -> C

code.

Finite automata (FAs) and regular languages

A RECOGNIZER takes language L and string x as

input, and responds YES if x∈L, or NO otherwise.

The finite automaton (FA) is one class of recognizer.

A FA is DETERMINISTIC if there is only one possible

transition for each <state,input> pair.

A FA is NONDETERMINISTIC if there is more than one

possible transition some <state,input> pair.

BUT both DFAs and NFAs recognize the same class

of languages: REGULAR languages, or the class of

languages that can be written as regular expressions.

NFAs

A NFA is a 5-tuple < S, ∑, move, s0, F >

S is the set of STATES in the automaton.

∑ is the INPUT CHARACTER SET

move( s, c ) = S is the TRANSITION FUNCTION

specifying which states S the automaton can move

to on seeing input c while in state s.

s0 is the START STATE.

F is the set of FINAL, or ACCEPTING STATES

NFA example

The NFA

has move() function:

and recognizes the language L = (a|b)*abb

(the set of all strings of a’s and b’s ending with abb)

The language defined by a NFA

An NFA ACCEPTS string x iff there exists a

path from s0 to an accepting state, such that

the edge labels along the path spell out x.

The LANGUAGE DEFINED BY a NFA N,

written L(N), is the set of strings it accepts.

Another NFA example

This NFA accepts L = aa*|bb*

Deterministic FAs (DFAs)

The DFA is a special case of the NFA except:

No state has an ε-transition

No state has more than one edge leaving it for the

same input character.

The benefit of DFAs is that they are simple to simulate:

there is only one choice for the machine’s state after

each input symbol.

Algorithm to simulate a DFA

Inputs:

Outputs:

Method:

string x terminated by EOF;

DFA D = < S, ∑, move, s0, F >

YES if D accepts x; NO otherwise

s = s0 ;

c = nextchar;

while ( c != EOF ) {

s = move( s, c );

c = nextchar;

}

if ( s ∈ F ) return YES

else return NO

DFA example

This DFA accepts L = (a|b)*abb

RE -> DFA

Now we know how to simulate DFAs.

If we can convert our REs into a DFA, we can

automatically generate lexical analyzers.

BUT it is not easy to convert REs directly into

a DFA.

Instead, we will convert our REs to a NFA

then convert the NFA to a DFA.

Converting a NFA to a DFA

NFA -> DFA

NFAs are ambiguous: we don’t know what state a NFA is in after

observing each input.

The simplest conversion method is to have the DFA track the

SUBSET of states the NFA MIGHT be in.

We need three functions for the construction:

ε-closure(s): the set of NFA states reachable from NFA state

s on ε-transitions alone.

ε-closure(T): the set of NFA states reachable from some

state s ∈ T on ε-transitions alone.

move(T,a): the set of NFA states to which there is a

transition on input a from some NFA state s ∈ T

Subset construction algorithm

Inputs:

Outputs:

Method:

a NFA N = < SN, ∑, tranN, n0, FN >

a DFA D = < SD, ∑, tranD, d0, FD >

add a state d0 to SD corresponding to ε-closure(n0)

while there is an unexpanded state di ∈ SD {

for each input symbol a ∈ ∑ {

dj = ε-closure(move(di,a))

if dj ∉ SD,

add dj to SD

tranN( di, a ) = dj

}

}

Examples: convert these NFAs

a)

b)

Converting a RE to a NFA

RE -> NFA

The construction is bottom up.

Construct NFAs to recognize ε and each element

a ∈ ∑.

Recursively expand those NFAs for alternation,

concatenation, and Kleene closure.

Every step introduces at most two additional NFA

states.

Therefore the NFA is at most twice as large as the

regular expression.

RE -> NFA algorithm

Inputs:

Outputs:

Method:

A RE r over alphabet ∑

A NFA N accepting L(r)

Parse r.

If r = ε, then N is

If r = a ∈ ∑ , then N is

If r = s | t, construct N(s) for s and N(t) for t then N is

RE -> NFA algorithm

If r = st, construct N(s) for s and N(t) for t then N is

If r = s*, construct N(s) for s, then N is

If r = ( s ), construct N(s) then let N be N(s).

Example

Use the NFA construction algorithm to build a NFA for

r = (a|b)*abb