25 Modern Theology

advertisement

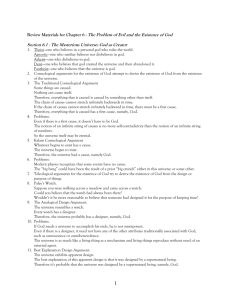

Modern Theology René Descartes Argument from Thought • • • • Where do we get our concept of God? It’s the concept of something perfect We never experience perfection So, the concept of God can’t come from experience • So, the concept of God is innate • It must come from something perfect • So, God must exist Descartes’s Premise • “Now it is manifest by the natural light that there must at least be as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in its effect. For, pray, whence can the effect derive its reality, if not from its cause? And in what way can this cause communicate this reality to it, unless it possessed it in itself?” Descartes’s Premise • “And from this it follows, not only that something cannot proceed from nothing, but likewise that what is more perfect -- that is to say, which has more reality within itself -- cannot proceed from the less perfect.” Descartes’s Argument • The cause of the idea of X must have at least as much reality as X – We get the idea of fire from fire – We get the idea of red from red things • The cause of our idea of God must have at least as much reality as God • Only God has as much reality as God • So, our idea of God must come from God Descartes’s Ontological Argument • God has all perfections • Existence is a perfection • So, God has existence Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) • Does God exist? • Place your bet • Total uncertainty— no data • What should you do? Pascal’s Wager • “Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is.” Pascal’s Wager • You believe You don’t believe • God Heaven Hell • No God Virtue Nothing • A bet on God can’t lose; a bet against God can’t win Kant’s Moral Argument • We can’t prove God’s existence rationally • But we can’t live and act except by assuming that God exists Kant’s Moral Argument • Bad things happen to good people; the wicked prosper • Why, then, be good? Kant’s Moral Argument • • • • It’s rational to be moral only if it’s rewarded That doesn’t happen in this life It must happen in another life So, there must be an afterlife, and a just God Leibniz (1646-1716) Leibniz • Principle of Sufficient Reason: “Nothing happens without a sufficient reason.” • So the universe— the series of contingent causes— must have a sufficient reason for its existence: • Something which is its own sufficient reason for existing: God Leibniz’s Argument • The world of efficient causes: • . . . <— c <— b <— a | G1 | G2 | God Sufficient Reason • By the principle of sufficient reason, everything exists for a reason, including the entire series of contingent causes • Take the entire history of the universe, finite or infinite, and ask why it exists • Why is there something rather than nothing? • Why is this particular history actual? • There must be a sufficient reason for the entire universe. And that is God Material v. Spiritual • The sufficient reason for everything cannot be the universe itself, or anything material, since matter is indifferent to existence or nonexistence • It must be something outside the realm of the material, temporal world that explains the existence of everything else • There must be something spiritual that explains the existence of everything, spiritual and material • And that can only be God Three Kinds of Evil • Metaphysical evil: the evil of anything in comparison with God, who is the most valuable being • Moral evil: evil done intentionally by human beings or other moral agents • Natural evil: evil in the universe for which no moral agent (other than perhaps God, the Creator) is responsible—for example, disease, old age, and death Best of All Possible Worlds • God is the omnipotent Creator of everything • God is omnibenevolent, or all-loving • So, this, the universe that God has created, is the best of all possible worlds Metaphysical Evil • There is metaphysical evil just in there being a universe at all • Thus God’s omnipotence and omnibenevolence are compatible with metaphysical evil • God, being omnibenevolent, would create a universe just to let creatures have their day in the sun • Thus metaphysical evil is not just compatible with an all-loving God; it is explained by God’s loving-kindness Moral Evil • Moral evil brought about by agents other than God results from free will • Free will is itself something good • Free-will theodicy: freedom is a valuable attribute of a creature • God does something good in creating beings who are free • Thus given a God who is omnibenevolent and the assumption that it is likely some with free will will sin, then moral evil is to be expected, too Natural Evil • The main problem is natural evil— disease, old age, and death • Leibniz contends that the universe is so complex, and its parts are so interdependent, that changing its structure to eliminate these natural evils would result in something even worse James Branch Cabell • “The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds; and the pessimist fears this is true.” Voltaire Candide (1759) • Voltaire mocks Leibniz’s view as Candide and his Leibnizian friend, Dr. Pangloss, witness the Seven Years’ War, the Lisbon earthquake, and other misfortunes Pangloss’s Theodicy • Poor Vision: “It is demonstrable that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end. Observe, for instance, the nose is formed for spectacles; therefore we wear spectacles.” Pangloss’s Theodicy • Venereal Disease: “... it was a thing unavoidable, a necessary ingredient in the best of worlds; for if Columbus had not caught in an island in America this disease, which contaminates the source of generation, and frequently impedes propagation itself, and is evidently opposed to the great end of nature, we should have had neither chocolate nor cochineal.” St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) Aquinas’s Design Argument • All bodies obey natural laws • All bodies obeying natural laws act toward an end • Therefore, all bodies act toward an end (Including those that lack awareness) Aquinas’s Design Argument • Things lacking awareness act toward a goal only under the direction of someone aware and intelligent • Therefore, all things lacking awareness act under the direction of someone aware and intelligent: God Aquinas’s Design Argument • All things lacking awareness act under the direction of someone aware and intelligent • The universe as a whole lacks awareness • Therefore, the universe as a whole acts under the direction of someone aware and intelligentnamely, God William Paley (1743-1805) William Paley • Suppose you find a watch – Intricate – Successful • You’d infer that it had an intelligent maker • Similarly, you find the universe – Intricate – Successful • You should infer it had an intelligent maker, God David Hume (1711-1776) Hume’s Criticisms • Analogy isn’t strong • Universe may be self-organizing • Why machine, rather than animal or vegetable? Hume’s Criticisms • Taking analogy seriously: – God not infinite – God not perfect • Difficulties in nature • Can’t compare to other universes • Maybe earlier, botched universes • Maybe made by committee Hume’s Skepticism • Variability: Many hypotheses are possible • Undecidability: We have no evidence that would let us select the most probable • So, we cannot establish God’s existence