_Layout 1

advertisement

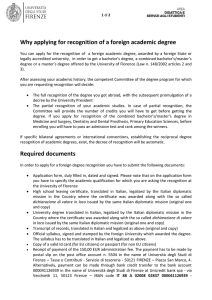

Tumori, 97: 442-448, 2011 Disparity in the “time to patient access” to new anti-cancer drugs in Italian regions. Results of a survey conducted by the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM) Stefania Gori1, Massimo Di Maio2, Carmine Pinto3, Oscar Alabiso4, Editta Baldini5, Enrico Barbato6, Giordano Domenico Beretta7, Stefano Bravi8, Orazio Caffo9, Luciano Canobbio10, Francesco Carrozza11, Saverio Cinieri12, Giorgio Cruciani13, Angelo Dinota14, Vittorio Gebbia15, Lucio Giustini16, Claudio Graiff17, Annamaria Molino18, Antonio Muggiano19, Giuliano Pandoli20, Fabio Puglisi21, Pierosandro Tagliaferri22, Silverio Tomao23, and Marco Venturini24 on behalf of AIOM Working Group “Interaction with Regional Sections” (2009-2011) 1Medical Oncology, “SM della Misericordia” Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliera, Perugia; Trials Unit, National Cancer Institute, “G Pascale” Foundation, Napoli; 3Medical Oncology Unit, “S Orsola-Malpighi” Hospital, Bologna; 4Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria "Maggiore della Carità", Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale "A Avogadro", Novara; 5Medical Oncology, “Campo di Marte” Hospital, Lucca; 6Ospedale “SG Moscati”, ASL CE, UOSD, Oncologia, Aversa (CE); 7Medical Oncology, Istituto Clinico Humanitas Gavazzeni, Bergamo; 8UO di Oncologia, Asl 1, Città di Castello (Perugia); 9Medical Oncology Department, “S Chiara” Hospital, Trento; 10 Medical Oncology, PA Micone Hospital, ASL3 Genovese, Genova Sestri P; 11Medical Oncology, "A Cardarelli" Hospital, Campobasso; 12Medical Oncology & Breast Unit, PO Senatore Antonio Perrino ASL Brindisi, via Appia, Brindisi, and Medical Department, Istituto Europeo di Oncologia (IRCCS) Milano; 13Medical Oncology, Umberto I Hospital, Lugo di Romagna (RA); 14 Medical Oncology, Azienda Ospedaliera S Carlo, Potenza; 15Medical Oncology, La Maddalena, Palermo; 16Medical Oncology, Zona Territoriale 11 Fermo; 17Medical Oncology, Central Hospital ASDAA/SABES, Bolzano/Bozen; 18Oncologia, Ospedale Civile Maggiore, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, Verona; 19Oncology Department, “A Businco” Hospital, ASL 8, Cagliari; 20 UO di Oncologia, ASL di Pescara, Pescara; 21Department of Clinical Oncology, University Hospital, Udine; 22Medical Oncology Unit, Tommaso Campanella Cancer Center and Magna Graecia University, Catanzaro; 23Dipartimento di Scienze e Biotecnologie Medico-Chirurgiche, Università degli Studi di Roma "Sapienza"; 24Medical Oncology, Ospedale Classificato Sacro Cuore Don Calabria, Negrar, Verona, Italy 2Clinical ABSTRACT Aims and background. In 2009, the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM) conducted a survey to describe the impact of regional pharmaceutical formularies on the disparity of access to eight new drugs among cancer patients treated in Italian regions. The survey documented some regional restrictions for some anti-cancer drugs. In the study, we analyzed the “time to patient access” to new anti-cancer drugs in Italian regions. Key words: anticancer drugs, disparity, time to patient access. Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this work. Methods. In March 2010, we analyzed the availability of 17 new anti-cancer drugs at a regional level, specifically the coherence of regional authorizations compared with national authorizations approved by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). In the regions with pharmaceutical formularies, we analyzed the characteristics of technicalscientific committees for the evaluation of inclusion of hospital drugs in these formularies. We also analyzed the time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to AIFA marketing authorization, the time from AIFA marketing authorization to patient availability, and the total time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to patient availability of the drugs in all Italian regions, for 11 of these drugs. Correspondence to: Dr.ssa Stefania Gori, Oncologia Medica, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Azienda Ospedaliera di Perugia, Via Dottori 1, 06122 Perugia, Italy. Tel +39-075-5784212; fax +39-075-5279082; e-mail stefania.gori@tin.it Results. Some drugs were included in all the regional pharmaceutical formularies, without restrictions, whereas other drugs were not included in one and others were Received November 5, 2010; accepted January 17, 2011. DISPARITY IN THE TIME TO PATIENT ACCESS TO NEW ANTICANCER DRUGS IN ITALY not included in more than one formulary. Median time from EMA to AIFA was 11.2 months (range, 2.9-17.1). Median time from AIFA to patient availability was 1.4 months (range, 0.0-50.5) in regions with drug formularies versus 0.0 months in regions without drugs formularies. Median total time from EMA to patient availability was longer in regions with formularies (13.3 months; range, 2.9-65.3) than in regions without formularies (11.2 months; range, 2.9-24.0), where drugs are immediately available after AIFA marketing authorization. Moreover, the interval was very long (range, 2.9-65.3) for some drugs in regions with formularies. Conclusions. The analysis confirmed that the presence of multiple hierarchical levels of drug evaluation can create disparity in drug availability for Italian citizens. Introduction As a general rule worldwide, new drugs obtain marketing authorization after an evaluation of scientific results obtained in clinical trials. Hospital drugs and thus anti-tumor drugs have to complete a series of obstacles before becoming available to Italian patients. Regarding the Italian market, when a new drug is evaluated through centralized European procedures, authorization is released by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Italy, as a member state of the European Community, automatically accepts drug marketing authorizations released by EMA. The implementation of EMA decisions is performed by the “European Procedures” Subcommittee of the Technical-Scientific Committee of the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA). Before adding the approved product to the National Pharmaceutical Formulary, AIFA decides the supply regimen and negotiates the reimbursement price with the authorization holder. After national marketing authorization by AIFA, a drug for hospital use is not immediately available in every hospital pharmacy. Its approval needs to undergo further steps that may be quite different from one region to the next, and even within a single region these steps may vary among the different health districts and hospitals1. There can be several levels of regional and local technical-scientific committees, each having the faculty of deciding the inclusion/exclusion of the drug in the specific pharmaceutical formulary. Consequently, the release of marketing authorization is performed at high hierarchical levels (EMA/AIFA), but the actual availability of the drug at each hospital is conditioned at local and lower hierarchical levels. According to this process, the number of drugs that are actually available for patients can be restricted. A local committee cannot insert in the local formulary a drug that is not included in the National Pharmaceutical Formulary, but it may decide to exclude from the local formulary a drug that 443 has been authorized by AIFA. Similarly, with a few exceptions, a hospital cannot include a drug in its formulary if the drug is not included in the regional pharmaceutical formulary, but may decide for exclusion of a drug that has been approved at the regional level. The existence of regional and local technical-scientific committees may cause disparities in the availability of drugs for patients of different regions as well as for patients treated at different hospitals within the same region. The problem of drug availability is particularly relevant in the oncology setting for two reasons: 1) patients want to receive the innovative drugs as part of their treatment, if indicated; 2) these new anti-cancer drugs most always have a very high price. In theory, the decision regarding the inclusion of new drugs in local formularies might be conditioned by the need for cost control by regional and local administrations, which can compromise the equality of treatment for Italian patients treated in different contexts (Jommi C, Bartoli S, Otto M. Analisi delle politiche regionali su accesso a farmaci innovativi. Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi – CERGAS [Centro di Ricerche sulla Gestione dell’Assistenza Sanitaria e Sociale], 2008). Disparity in access to anti-cancer treatments is a relevant problem, as has been recently underlined by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, although the social and health context in the United States is profoundly different from the Italian reality2. In 2009, the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM) conducted a survey to describe the impact of the existence of regional pharmaceutical formularies on the disparity of access to eight new drugs among cancer patients treated in different Italian regions. Results of the survey evidenced some regional restrictions for some drugs3. AIOM conducted the study in 2010 with the aim of evaluate the differences in “time to patient access” of the new anticancer drugs among Italian regions and any possible disparity in the time to availability. Methods Information for this study was collected with the help of coordinators of each regional section of AIOM. For each region and for the two autonomous provinces that form the Trentino-Alto Adige Special region, information was collected on the existence of a regional pharmaceutical formulary/provincial pharmaceutical formulary. For regions where a regional/provincial pharmaceutical formulary was available, the most updated version of the formulary at March 2010 was examined, in order to verify the inclusion of the analyzed drugs, and the coherence with the national marketing authorization indication approved by AIFA. Moreover, the characteristics of the technical-scientific committees for the evaluation 444 S GORI, M DI MAIO, C PINTO ET AL of hospital drugs to be included in regional formularies were analyed, both in terms of composition and the scheduling of meetings. We considered 17 drugs registered by AIFA from 2005 to 2009: bevacizumab, bortezomib, cetuximab, dasatinib, erlotinib, ibritumomab, imatinib, lapatinib, nilotinib, panitumumab, pemetrexed, rituximab, sorafenib, sunitinib, temsirolimus, trabectedin, and trastuzumab. We analyzed, in all Italian regions and autonomous provinces, 3 time intervals: time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to AIFA marketing authorization (Time 1), time from AIFA marketing authorization to regional availability (Time 2), and the total time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to regional availability (Time 3) for the following drugs: bevacizumab, cetuximab, erlotinib, ibritumomab, lapatinib, nilotinib, pemetrexed, sorafenib, sunitinib, trabectedin, and trastuzumab. Results As of March 2010, 15 Italian regions (Abruzzo, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Emilia Romagna, Lazio, Liguria, Molise, Puglia, Tuscany, Sardinia, Sicily, Umbria, Valle d’Aosta, and Veneto) and the autonomous province of Trento had regional/provincial pharmaceutical formularies. Four regions (Piemonte, Lombardy, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Marche) and the autonomous province of Bolzano did not have regional pharmaceutical formularies. The same situation was observed in the previous analysis3. In Italian regions and in the autonomous province with regional formularies, there are technical-scientific committees for the evaluation of hospital drugs to be included in these formularies. The characteristics of these technical-scientific committees are reported in Table 1. Some committees do not include a medical oncologist among current members. Declared schedule of meetings was different among the regions (ranging from monthly to every 6 months), and the actual number of meetings during 2009 was very different, ranging from 0 and 11. In Italian regions and in the autonomous province with regional formularies, it was observed that in the majority of cases the updated versions (at March 2010) of regional pharmaceutical formularies used for the present analysis included the 17 analyzed drugs, with therapeutic indication coherent with national marketing authorization indications approved by AIFA (Table 2). However, eight of the 17 drugs (sorafenib, nilotinib, dasatinib, ibritumomab, lapatinib, trabectedin, panitumumab and temsirolimus) were not included in some of the existing regional pharmaceutical formularies. Six drugs (cetuximab, bevacizumab, erlotinib, sunitinib, pemetrexed and nilotinib) presented some restrictions in some regions. In some regions, patient-specific requests were needed for some drugs. In four Italian regions (Piemonte, Lombardy, FriuliVenezia Giulia, Marche) and in the autonomous province of Bolzano (which did not have regional pharmaceutical formularies), national marketing authorizations were immediately applicable. Table 1 - Technical-scientific committees for the evaluation of hospital drugs to be included in regional formularies (analysis performed in February 2010) Committee members Region Abruzzo Basilicata Calabria Campania Emilia-Romagna Lazio Liguria Molise Puglia Sardinia Sicily Tuscany (North-West Wide-Area) Trento Province Umbria Valle d’Aosta Veneto Pharmacist Pharmacologist X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X General Medical Infectivologist Cardiologist Other Number of Meeting practitioners oncologist medical schedule oncologists in the Committee X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X 2 0 0 0 2 1 5 1* 1 1 1 -** Monthly nr Every 2 mo Monthly Monthly Monthly Every 6 mo Every 6 mo Monthly Monthly Monthly Not regular 10 0 6 10 11 7 1 1 6 5 4 2 X X X X X X 1 1 1 1 Monthly Every 3 mo Every 3 mo Every 2 mo 10 3 4 7 X X X X X X X X X** X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X No. of meetings in 2009 *The number of medical oncologists varies according to the topics discussed at each meeting. **Presence of medical oncologist is on demand. nr, not reported. Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Limits Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Limits Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes NO Yes Yes Yes Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes Yes Limits Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes No No Yes No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Limits Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes No No No No PSR No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes PSR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes PSR Yes, drug included in the formulary; No, drug not included in the formulary; PSR, use of drug allowed by patient-specific request; Limits, drug included in the formulary, with limitations, A.P. Trento, autonomous province of Trento. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Limits Formulary Cetuximab Bevacizumab Trastuzumab Rituximab Erlotinib Sorafenib Sunitinib Pemetrexed Lapatinib Trabectedin Nilotinib Bortezomib Panitumumab Dasatinib Temsirolimus Imatinib Ibritumomab analyzed (date) Abruzzo 02/2010 Basilicata 2008 Calabria 2008 Campania 2005 Emilia 02/2010 Romagna Lazio 12/2008 Liguria 06/2008 Molise 10/2007 Puglia 09/2009 Sardinia 12/2009 Sicily 02/2009 Tuscany 06/2007 (North-West Wide Area) A.P. Trento 11/2009 Umbria 11/2009 Valle d’Aosta 01/2010 Veneto 02/2010 Region Table 2 - Inclusion of selected drugs in Italian regional pharmaceutical formularies, as of March 2010 DISPARITY IN THE TIME TO PATIENT ACCESS TO NEW ANTICANCER DRUGS IN ITALY 445 446 Time to drug availability for neoplastic patients in Italian regions The time to drug availability for neoplastic patients in Italian regions is shown in Figure 1. Tables 3 and 4 report the time to drug availability in regions with and without regional drug formularies, respectively. Both tables report the time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to AIFA marketing authorization (Time 1), the time from the AIFA marketing authorization to patient availability (Time 2), and the total time from EMA (CMPH) authorization to patient availability of the drug (Time 3). In the 15 regions and in the autonomous province of Trento that have regional formularies, time elapsed before the availability of the drugs for the patients (Time 3) is given by the sum of the two intervals: from the EMA approval to AIFA marketing authorization (Time 1: 11.2 months; range, 2.9-17.1), and from AIFA marketing authorization to drug inclusion in the regional formulary (Time 2: 1.4 months; range, 0.0-50.5) (Table 3). The overall median time required before patient access (Time 3) in these regions was 13.3 months (range, 2.9-65.3) (Table 3). Moreover, the range of the values for Time 3 demonstrates that the interval can be very long for some drugs: 65.3 months for cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer, and 40.4 months for sorafenib in metastatic kidney in the regions with regional drug formularies (Table 3). In the 4 regions and in the autonomous province of Bolzano that do not have regional formularies, Time 2 is zero by definition and time of regional availability of S GORI, M DI MAIO, C PINTO ET AL drugs (Time 3) is dependent only on the time from EMA approval to AIFA marketing authorization (Time 1: 11.2 months; range, 2.9-17.1) (Table 4). So, in these regions, the overall median time required before patient access (Time 3) was 11.2 months (range, 2.9-24.0), shorter than in regions with regional formularies (13.3 months; range, 2.9-65.3). Moreover, also the range of values for Time 3 was more limited (range, 2.9-24.0) than for regions with regional formularies (range, 2.9-65.3). Discussion The present analysis, conducted as of March 2010, was based on 17 new anti-neoplastic agents that were registered by AIFA with indications for use in oncology over the period 2005-2009. This series of drugs is larger than the eight drugs considered in the previous publication3, and more adequately represents the increasing number of agents that have been registered in recent years for use in oncology. In Italian regions with regional pharmaceutical formularies, all analyzed drugs were included in formularies with therapeutic indication coherent with national marketing authorization indications approved by AIFA, but eight of the 17 drugs were not included in some of the existing regional pharmaceutical formularies and six drugs presented some regional restrictions. In some regions, patient-specific requests were needed for some drugs. Figure 1 - Median total time from the EMA (CHMP) authorization to regional availability of the drug (Time 3). EMA, European Medicines Agency; CHMP, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma. DISPARITY IN THE TIME TO PATIENT ACCESS TO NEW ANTICANCER DRUGS IN ITALY Table 3 - Time to availability of anticancer drugs in Italian regions with regional drug formularies (March 2010) Time 1 Interval EMA-AIFA Median (range), months Time 2 Interval AIFA-regional availability Median (range), months Time 3 Interval EMA-regional availability Median (range), months 2.9 (2.9-2.9) 0.0 (0-0) 2.9 (2.9-2.9) 16.9 (16.9-16.9) 5.1 (2.1-13.6) 22.0 (18.9-30.4) SunitinibAIFA 2006 6.9 (6.9-6.9) 7.3 (1.9-19.3) 14.1 (8.7-26.1) SorafenibAIFA 2006Kidney cancer 4.1 (4.1-4.1) 2.8 (0.3-36.3) 6.9 (4.4-40.4) SorafenibAIFA 2008hepatocellular carcinoma 9.1 (9.1-9.1) Drug Trastuzumabbreast cancer, adjuvant treatment Trabectedin Pemetrexed AIFA 2009 NSCLC – First line Table 4 - Time to availability of anticancer drugs in Italian regions without regional drug formularies (March 2010) Drug 9.4 (9.4-26.4) Time 1 Interval EMA-AIFA Median (range), months Time 2 Time 3 Interval Interval AIFA-regional EMA-regional availabilty availability Median Median (range), (range), months months 2.9 (2.9-2.9) 0.0 (0-00) 2.9 (2.9-2.9) 16.9 (16.9-16.9) 0.0 (0.0-7.1) 20.4 (16.9-24) Sunitinib-AIFA 2006 6.9 (6.9-6.9) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 6.9 (6.9-6.9) Sorafenib-AIFA 2006kidney cancer 4.1 (4.1-4.1) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 4.1 (4.1-4.1) Sorafenib-AIFA 2008hepatocellular carcinoma 9.1 (9.1-9.1) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 9.1 (9.1-9.1) 13.9 (13.9-13.9) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 13.9 (13.9-13.9) Nilotinib 8.6 (8.6-8.6) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 8.6 (8.6-8.6) Trastuzumabbreast cancer, adjuvant treatment Trabectedin 0.2 (0.2-17.2) 447 Pemetrexed AIFA 2009 NSCLC – First line 13.9 (13.9-13.9) 0.4 (0.4-5.5) 14.3 (14.3-19.3) Nilotinib 8.6 (8.6-8.6) 5.8 (0.8-17.8) 14.5 (9.4-26.4) Lapatinib 11.3 (11.3-11.3) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 11.3 (11.3-11.3) Lapatinib 11.3 (11.3-11.3) 3.9 (1.4-8.5) 15.2 (12.7-19.7) Ibritumomab Ibritumomab 17.1 (17.1-17.1) 32.4 (15.4-45.4) 49.5 (32.5-62.5) 17.1 (17.1-17.1) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 17.1 (17.1-17.1) ErlotinibAIFA 2006- NSCLC 13.0 (13-13) 0.0 (0.0-7.7) 13.0 (13-20.7) ErlotinibAIFA 2006-NSCLC 13.0 (13.0-13.0) 0.0 (0.0-0) 13.0 (13.0-13.0) CetuximabAIFA 2005Colorectal cancer 14.8 (14.8-14.8) 11.4 (0-50.5) 26.3 (14.8-65.3) Cetuximab-AIFA 2005colorectal cancer 14.8 (14.8-14.8) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 14.8 (14.8-14.8) Cetuximab-AIFA 2006Head and neck cancer 8.7 (8.7-8.7) 0.0 (0-0) 8.7 (8.7-8.7) 8.7 (8.7-8.7) 9.5 (0-22.7) 18.2 (8.7-31.4) Cetuximab-AIFA 2009colorectal cancer 13.3 (13.3-13.3) 0.0 (0.0-0.0) 13.3 (13.3-13.3) 11.2 0.0 11.2 (11.2-11.2) (0.0-0.0) CetuximabAIFA 2006Head and neck cancer CetuximabAIFA 2009Colorectal cancer 13.3 (13.3-13.3) Bevacizumab AIFA 2005Colorectal cancer, 1st line 11.2 (11.2-11.2) 0.0 (0.0-19.1) 11.2 (11.2-30.3) 11.2 (2.9-17.1) 1.4 (0.0-50.5) 13.3 (2.9-65.3) Total 0.0 (0-4.8) 13.3 (13.3-18.1) Bevacizumab AIFA 2005-colorectal cancer, 1st line Total Time 1, the time from the EMA (CMPH) authorization to AIFA marketing authorization. Time 2, the time from the AIFA marketing authorization to regional availability of these drugs. Time 3, the total time from the EMA (CMPH) authorization to regional availability of the drug. These observations revealed that, in the majority of cases, the regional technical-scientific committee (or equivalent) confirmed the positive decision made at the higher hierarchical level (AIFA). However, a significant 11.2 (2.9-17.1) 0.0 (0.0-7.1) (11.2-11.2) 11.2 (2.9-24.0) Time 1, the time from the EMA (CMPH) authorisation to AIFA marketing authorization. Time 2, the time from the AIFA marketing authorisation to regional availability of these drugs. Time 3, the total time from the EMA (CMPH) authorisation to regional availability of the drug. number of drugs had been excluded from the formularies in one or more regions: in these instances, the inferior hierarchical level (the lower level authority at the regional level) did not take into account the decision of the higher authority (AIFA at the national level). This occurred despite, at a higher level, the scientific evidence supporting the drug had been judged sufficient to warrant marketing authorization. On the contrary, in four 448 Italian regions and in the autonomous province of Bolzano which did not have regional pharmaceutical formularies, national marketing authorizations were immediately applicable. The presence of sub-national pharmaceutical formularies is a potential element of disparity in the access to pharmacologic therapy for Italian patients. However, it should be noted that regional formularies are made because they can be a tool for efficient allocation of resources and for appropriate prescription. The analysis of time elapsed before the availability of the drug for the neoplastic patient adds some relevant elements to the issue of disparity between Italian regions. In the regions with regional formularies, the overall median time required before patient access (Time 3) was 13.3 months (range, 2.9-65.3). Moreover, the range of the values for Time 3 demonstrates that the interval can be very long for some drugs: 65.3 months for cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer and 40.4 months for sorafenib in metastatic kidney in the regions with regional drug formularies (Table 3). In regions without regional formularies, the overall median time required before patient access (Time 3) is shorter: 11.2 months (range, 2.9-24.0), because this time is dependent only on the time from EMA approval to AIFA marketing authorization. Furthermore, the total time to availability of anticancer drugs in Italian regions without regional drug formularies is independent from other bureaucratic issues such as the difference in the frequency of technical-scientific regional commission meetings, which in regions with drug formularies creates further disparity between Italian patients. Currently, the declared schedule of meetings (ranging from monthly to every 6 months) and the actual number of meetings during 2009 was very different, ranging from 0 and 11. Such differences can also be a potential element of disparity in the access to anti-neoplastic drugs for Italian patients because they prolong the time already elapsed between S GORI, M DI MAIO, C PINTO ET AL the AIFA marketing authorization to regional availability of the drug. In conclusion, the presence of multiple hierarchical levels of drug evaluation necessary for inclusion in the relative regional, provincial or wide-area formularies, as well as those of local health authorities or hospitals, is a potential element of disparity in the access to pharmacologic therapy for Italian neoplastic patients. Moreover, the regional/local processes create time delays and discrepancies, and there is no guarantee that such disparities will not continue to widen. In the ideal scenario, medical oncologists should be able to consider and prescribe for their patients all drugs that have received national marketing authorizations. The commissions responsible for the territorial formularies have the responsibility of evaluating and containing drug care costs, but being at a lower hierarchical level they may better achieve this objective through monitoring of the appropriate use of authorized drugs. References 1. Pammolli F, Integlia D: I farmaci ospedalieri tra Europa, Stato, Regioni e cittadini. Federalismo per i cittadini o federalismo di burocrazia? CERM – Competitività, Regolazione, Mercati. Roma. Quaderno n. 1, 2009. Available at http://www.cermlab.it/pub/group/q/item/102 (last accessed January 20, 2011). 2. Goss E, Lopez AM, Brown CL, Wollins DS, Brawley OW, Raghavan D: American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement: Disparities in Cancer Care. J Clin Oncol, 27: 2881-2885, 2009. 3. Gori S, Di Maio M, Pinto C, Alabiso O, Baldini E, Beretta GD, Caffo O, Caroti C, Crinò L, De Laurentiis M, Dinota A, Di Vito F, Gebbia V, Giustini L, Graiff C, Guida M, Lelli G, Lombardo M, Muggiano A, Puglisi F, Romito S, Salvagno L, Tagliaferri P, Terzoli E, Venturini M, on behalf of AIOM Working Group “Interaction with Regional Sections” (2007-2009): Differences in the availability of new anti-cancer drugs for Italian patients treated in different regions. Results of analysis conducted by the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM). Tumori, 96: 1010-1015, 2010.