Introducing Complex Adaptive Systems Theory and Agent

advertisement

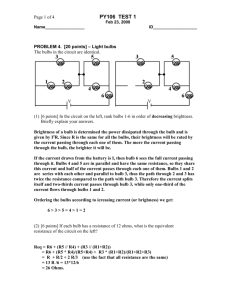

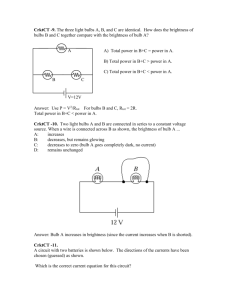

A simple system (Kauffman 1993) Imagine a system of three (n=3) light bulbs (A,B,C), each of which can be either off (0) or on (1) (s=2). Each light bulb is connected to the other two (k=2) There are 23 (sn) possible initial states, also known as the “design space” at (t=0): t=0 A B C 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 0 3 0 1 0 4 0 0 1 5 1 1 0 6 1 0 1 7 0 1 1 8 1 1 1 Next, establish a “rule” to determine whether a bulb is “on” or “off” in subsequent iterations: A bulb will turn on or stay on only if both of its partners are on (the Boolean and function) What happens? t=0 • • A B C and and and 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 3 0 4 t=1 A B C and and and 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 3 0 0 0 1 4 5 1 1 0 6 1 0 7 0 8 1 t=2 A B C and and and 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 5 0 0 1 5 0 0 0 1 6 0 1 0 6 0 0 0 1 1 7 1 0 0 7 0 0 0 1 1 8 1 1 1 8 1 1 1 Our eight initial states have resolved down to just two in only two iterations If we subsequently turn one or two random bulb under conditions 1-7, the system quickly reestablishes its equilibrium of all bulbs off – We must turn on all three bulbs to escape this “basin of attraction” • However, if we turn off only one bulb under condition 8, within two iterations all bulbs will be off! Next, try the Boolean or: A bulb will turn on or stay on if either of its partners is on. t=0 A B C or or or 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 3 0 4 t=1 A B C or or or 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 1 0 3 1 0 0 1 4 5 1 1 0 6 1 0 7 0 8 1 t=2 A B C or or or 1 0 0 0 1 2 1 1 1 0 1 3 1 1 1 1 1 0 4 1 1 1 5 1 1 1 5 1 1 1 1 6 1 1 1 6 1 1 1 1 1 7 1 1 1 7 1 1 1 1 1 8 1 1 1 8 1 1 1 The mirror effect of the Boolean and: • Still only two equilibria • “All on” becomes the strong attractor, “all off” is much less stable Now for some fun! Let bulb A have the or condition while B and C have the and condition. What happens? t=0 A B C or and and 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 3 0 4 t=1 A B C or and and 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 3 1 0 0 1 4 5 1 1 0 6 1 0 7 0 8 1 t=2 A B C or and and 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 1 0 0 4 0 0 0 5 1 0 1 5 1 1 0 1 6 1 1 0 6 1 0 1 1 1 7 1 0 0 7 0 0 0 1 1 8 1 1 1 8 1 1 1 We now have three “basins of attraction”: • Conditions 1-4 and 7 become “all off” • Condition 8 becomes “all on” • Conditions 5 and 6 are “A on, B and C alternating” • The system is still quick to “adapt” to randomly changing the state of any bulb, but will quickly fall into one of the three “attractors” What does our simple system demonstrate? The number of stable states is much smaller than the number of initial states • This “structure” is an “emergent” property not reducible to the individual bulbs or the rules by which they “behave,” but rather results from their interactions The system can “adapt” to changes • There is a range of attractor “strength,” with some being quite resistant to change, others unable to persist after any change, and still others somewhere in between The system is sensitive to changes in initial conditions: • Small differences in initial states can result in significantly different end states • The system is described as “chaotic,” not because of any randomness at work in the system but because of this sensitivity • Imagine a chaotic system in which the differences in initial conditions are below the level of measurement – seemingly identical initial states would resolve to very different states, perhaps suggesting some “randomness” at play when there is none! Conway’s Game of Life Extend Kauffman’s Boolean network example a bit. Think of a lattice grid (i.e. a chessboard), in which each square is an “agent” surrounded by eight neighbors. • As with our light bulbs, each agent can be either “on” or “off” • The decision rules are as follows: • • • If an agent is “off” it will turn “on” if it has exactly three neighbors “on” If an agent is “on” it will stay “on” if it has either two or three neighbors “on” Under all other conditions an agent will be “off” Now, allow for a “landscape” of 100 x 180 agents. • This is 218,000 (or ~105400) possible initial states (the design space) • Number of seconds since the universe began: ~10 11 • Number of particles in the universe: ~10 82 Conway’s Game of Life • Despite the Vast number of stable states, only a handful of configurations are stable • Thus our models can meaningfully sample the design space! • The system is adaptive • The combination of rules is not arbitrary: most sets of rules either generate games in which nothing interesting happens or the system cycles through the design space • • • One question would be: what is the likelihood of randomly generating a set of rules that displays complex adaptive behavior (A: very small for even simple systems) Turning the question around: how many systems that don’t have rules generating complexity and adaptation survive for long? A: very few! So we find many complex adaptive systems not because they are relatively common at the outset but they are the only ones that persist! Shelling’s Segregation Model The Standing Ovation Problem One of a potentially very large number of problems in which “decentralized dynamical systems consisting of spatially distributed agents who respond to local information.” • “Structure” (i.e. Standing Ovation) is an emergent property • Agents are spatially related with limited information In a simple version of the SOP, an agent will perceive the quality of a performance, make an initial decision to stand based on the perceived quality relative to an internal willingness to stand. After the first iteration, agents will choose to change their initial behavior based on how many neighbors are standing and the agent’s threshold for conformity (perhaps relative to her initial preference). The Standing Ovation Problem: Modeling Issues • How much external information does each agent receive? • How many neighbors does each agent have? • Does the neighborhood size vary? Why? • Does each neighbor have the same weight or does influence vary? • Are some agents more influential to all agents who “see” them or only to some (i.e. “friends”)? • Why? The Standing Ovation Problem: Modeling Issues • What is the relative balance between initial agent preference (to stand or remain seated) and neighborhood information? • Is this balance the same for all agents or distributed in some other way? • What assumptions drive this decision? • Is a decision to stand reversible? Why or why not? • How many iterations should the model be run? Comparing mathematical and computational approaches to SOP Both approaches: • Often generate the “wrong” equilibrium (i.e. most people end up standing even though most did not like the play) • Find the stronger the pressure to conform the more often “wrong” equilibria occur • The plot of people standing is an “s” curve, as diffusion models predict • People at the front of the audience can have a large impact Comparing mathematical and computational approaches to SOP However, mathematical models in some respects perform poorly compared to computational models: • They imply that all agents eventually agree, a rare outcome in computational models • They tend to ignore the sequencing of updating, which is shown to be important • The predicted “s” curve can be easily changed in computational models to reduce the slope • Mathematical models, by only counting the number of standing agents, fail to replicate the spatial dynamics generating the “s” curve