Chapters 9, 13

advertisement

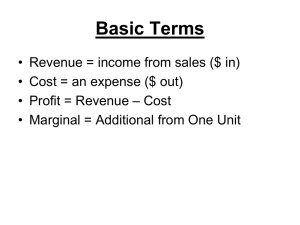

CHAPTERS 10, 14, 15 Concentration, Monopolistic Competition, and Oligopoly Varieties of Market Structure We have studied the two extremes of market structure — perfect competition and monopoly. Most industries fall somewhere between those two, differing along two significant scales: Number of suppliers of output The degree of product differentiation Monopolistic Competition Monopolistic competition is a market structure in which a large number of firms compete with each other by making similar but slightly different products. Making a product slightly different from the product of a competing firm is called product differentiation. Oligopoly Oligopoly is a market structure in which a small number of producers compete with each other. Some oligopolies (aluminum can manufacturing) produce identical products. Others (automobiles) produce differentiated products. Measures of Concentration Industries in which only a few firms supply all the output are said to be concentrated. Economists have developed two measures of concentration: The four-firm concentration ratio The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index The Four-Firm Concentration Ratio The four-firm concentration ratio is the percentage of total industry sales (in dollars) made by the four largest firms. The range of this measure is from 0 to 100. 0 is perfect competition 100 means there are four or fewer firms in the industry Ratio < 60 considered competitive Concentration Ratio Calculations Smartphone OS Market Share Firm Percentage of Industry Sales 2009 2010 2011 Jan 2012 RIM Blackberry 37% Apple iPhone 21% Microsoft Windows Mobile 27% Android 1% Palm 8% Linux 3% Symbian 3% 27% 28% 14% 23% 2% 3% 3% 23% 26% 9% 36% 1% 3% 2% 6% 43% 2% 47% 0% 1% 1% Top 4 sales 85% 92% 94% 98% Other firms 15% 8% 6% 2% Concentration Ratio Calculations PCs (Excluding Tablets) Firm Worldwide Market Share 2006 2009 2013 Dell HP Acer Lenovo Toshiba Asus Others 15.9% 15.9% 7.6% 7.0% 3.8% 1.2% 48.6% 12.1% 19.1% 12.9% 8.0% 5.0% 2.3% 40.6% 11.6% 16.2% 8.1% 16.9% 3.4% 6.3% 37.5% Top 4 46.4% 52.1% 52.8% Concentration Ratio Calculations Printers Sales Firm Fran’s Ned’s Tom’s Jill’s Top 4 sales Other 1,000 firm’s sales Industry sales Four-firm concentration ratios: (millions of dollars) 2.5 2.0 1.8 1.7 8.0 1,592.0 1,600.0 Printers: 8/1,600 100 = 0.5% The HerfindahlHirschman Index (HHI) The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is the sum of the squared market shares of the largest 50 firms in an industry. For example, if there are four firms in an industry with market shares of 50%, 25%, 15%, and 10%, the HHI is: 502+252+152+102 = 3,450 Using the HHI A monopoly will have an HHI of 10,000 (1002). The Justice Department defines a competitive market as one with an HHI less than 1,000 (<100 is regarded as highly competitive). Markets with HHI values between 1,000 and 1,800 are regarded as moderately competitive. Markets with HHI values above 1,800 are regarded as uncompetitive. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) uses the HHI to evaluate potential mergers. If the original HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800, any merger that raises the HHI by 100 or more is challenged. If the original HHI is greater than 1,800, any merger that raises the HHI by more than 50 is challenged. Antitrust Law Antitrust law provides an alternative way in which the government may influence the marketplace. Antitrust law is the law that regulates oligopolies and prevents them from becoming monopolies or behaving like monopolies. The Antitrust Laws The two main antitrust laws are The Sherman Act, 1890 The Clayton Act, 1914 Antitrust Law The Sherman Act outlawed any “combination, trust, or conspiracy that restricts interstate trade,” and prohibited the “attempt to monopolize.” Antitrust Law A wave of merger activities at the beginning of the 20th century produced a stronger antitrust law, the Clayton Act, and created the Federal Trade Commission. The Clayton Act made illegal specific business practices such as price discrimination, interlocking directorships, and acquisition of a competitor’s shares if the practices “substantially lessen competition or create monopoly.” Antitrust Law Table 15.6 (next slide) summarizes the Clayton Act and its amendments, the Robinson-Patman Act passed in 1936 and the Cellar-Kefauver Act passed in 1950. The Federal Trade Commission, formed in 1914, looks for cases of “unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive business practices.” Antitrust Law Antitrust Law Price Fixing Always Illegal Price fixing is always a violation of the antitrust law. If the Justice Department can prove the existence of price fixing, there is no defense. Antitrust Law Three Antitrust Policy Debates But some practices are more controversial and generate debate. Three of them are Resale price maintenance Tying arrangements Predatory pricing Antitrust Law Resale Price Maintenance Most manufacturers sell their product to the final consumer through a wholesale and retail distribution chain. Resale price maintenance occurs when a manufacturer agrees with a distributor on the price at which the product will be resold. Resale price maintenance is inefficient if it promotes monopoly pricing. But resale price maintenance can be efficient if it provides retailers with an incentive to provide an efficient level of retail service in selling a product. Antitrust Law Tying Arrangements A tying arrangement is an agreement to sell one product only if the buyer agrees to buy another different product as well. Some people argue that by tying, a firm can make a larger profit. Where buyers have a differing willingness to pay for the separate items, a firm can price discriminate and take a larger amount of the consumer surplus by tying. Antitrust Law Predatory Pricing Predatory pricing is setting a low price to drive competitors out of business with the intention of then setting the monopoly price. Economists are skeptical that predatory pricing actually occurs. A high, certain, and immediate loss is a poor exchange for a temporary, uncertain, and future gain. No case of predatory pricing has been definitively found. Antitrust Law Mergers and Acquisitions The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) uses guidelines to determine which mergers to examine and possibly block. The Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) is one of those guidelines. As indicated earlier If the original HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800, any merger that raises the HHI by 100 or more is challenged. If the original HHI is greater than 1,800, any merger that raises the HHI by more than 50 is challenged. Historical Example of Using the HHI to Evaluate Mergers Carbonated Soft Drink Merger Proposals in 1986 Market Share Firm No Mergers Pepsi/7-Up Coke/Dr. Pepper Both Mergers Coca Cola Pepsi Cola Dr. Pepper 7-Up RJR Others (assume 15 equal share firms) 39% 28% 7% 6% 5% 15% 39% 34% 7% 5% 15% 46% 28% 6% 5% 15% 46% 34% 5% 15% HHI 2,430 2,766 2,976 3,312 Market Structure Characteristic # Firms in Industry Perfect Competition Monopolistic Competition Oligopoly Monopoly Many Many Few One Identical or Differentiated No Close Substitutes Product Identical Differentiated Barriers to Entry None (Free Enty) None (Free Entry) Considerable Considerable or Legal Barriers Firm’s Control over Price None Some Considerable Considerable or Regulated Concentration Ratio 0 Low (<50) High (>50) 100 HHI <100 100 to 1,000 >1,000 10,000 (cont.) Market Structure (Cont.) Perfect Characteristic Competition Monopolistic Competition Oligopoly Monopoly Long Run Profits No (P=ATC) No (P=ATC) Yes (P>ATC) Yes (P>ATC) Allocative Efficiency Yes (P=MC) No (P>MC) No (P>MC) No (P>MC) Examples Wheat, Corn Food, Clothing, Restaurants, Shoes, Computers Autos (Domestic), Cereals Local Phone Service, CableTV, Electric and Gas Utilities Limitations of Concentration Measures There are three main reasons why concentration ratios may be misleading as measures of market structure: The geographical scope of the market Barriers to entry and firm turnover The correspondence between a market and an industry Geographical Scope of Market Concentration ratio calculations are based on national market data. Some goods (such as newspapers) are sold in regional markets. Other goods and services (automobiles) are sold in global markets. In either case, concentration ratios are misleading. Limitations of Concentration Measures Market and Industry Markets are narrower than industries Firms make many different products Firms switch from one market to another Market and Industry Concentration ratios are calculated using the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Markets often do not correspond neatly to industries. Westinghouse is classified as an electrical goods and equipment producer. They actually produce many other non-electrical items. Barriers to Entry and Turnover Measures of concentration do not tell us anything about the extent and severity of barriers to entry in an industry. Even in markets that are highly concentrated, there may be competition if entry and exit cause a large amount of turnover. Concentration Measures for the U.S. Economy Motor vehicles, light bulbs, household laundry equipment, chewing gum, and breakfast cereals are highly concentrated oligopolies. Pet food, computers, and soft drinks, are moderately competitive Women’s clothing, ice cream, concrete blocks and bricks, and commercial printing are highly competitive. Concentration Measures in the United States Market Structures in the U.S. Economy Between 1939 and 1980, the U.S. economy became increasingly competitive. In 1980, three-fourths of the value of goods and services produced in the U.S. was sold in markets that are highly competitive. Monopolies accounted for only about 5% of total sales. Since 1980, there has been even more competition (due to global trading), but there have also been many mergers of oligopolies leading to greater concentration in certain oligopolistic industries (such as telecommunications) Monopolistic Competition Monopolistic competition is a market with the following characteristics: A large number of firms. Each firm produces a differentiated product. Firms compete on product quality, price, and marketing. Firms are free to enter and exit the industry. Monopolistic Competition Large Number of Firms The presence of a large number of firms in the market implies: Each firm has only a small market share and therefore has limited market power to influence the price of its product. Each firm is sensitive to the average market price, but no firm pays attention to the actions of the other, and no one firm’s actions directly affect the actions of other firms. Collusion, or conspiring to fix prices, is impossible. Monopolistic Competition Product Differentiation Firms in monopolistic competition practice product differentiation, which means that each firm makes a product that is slightly different from the products of competing firms. Monopolistic Competition Competing on Quality, Price, and Marketing Product differentiation enables firms to compete in three areas: quality, price, and marketing. Quality includes design, reliability, and service. Because firms produce differentiated products, each firm has a downward-sloping demand curve for its own product. But there is a tradeoff between price and quality. Differentiated products must be marketed using advertising and packaging. Monopolistic Competition Entry and Exit There are no barriers to entry in monopolistic competition, so firms cannot earn an economic profit in the long run. Examples of Monopolistic Competition Figure 13.1 on the next slide shows market share of the largest four firms and the HHI for each of ten industries that operate in monopolistic competition. Monopolistic Competition The red bars refer to the 4 largest firms. Green is the next 4. Blue is the next 12. The numbers are the HHI. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Short-Run Economic Profit A firm that has decided the quality of its product and its marketing program produces the profit maximizing quantity at which its marginal revenue equals its marginal cost (MR = MC). Price is determined from the demand curve for the firm’s product and is the highest price the firm can charge for the profit-maximizing quantity. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Figure 13.2(a) shows a short-run equilibrium for a firm in monopolistic competition. It operates much like a single-price monopolist. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition The firm produces the quantity at which price equals marginal cost and sells that quantity for the highest possible price. It earns an economic profit (as in this example) when P > ATC. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Long Run: Zero Economic Profit In the long run, economic profit induces entry. And entry continues as long as firms in the industry earn an economic profit—as long as (P > ATC). In the long run, a firm in monopolistic competition maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which its marginal revenue equals its marginal cost, MR = MC. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition As firms enter the industry, each existing firm loses some of its market share. The demand for its product decreases and the demand curve for its product shifts leftward. The decrease in demand decreases the quantity at which MR = MC and lowers the maximum price that the firm can charge to sell this quantity. Price and quantity fall with firm entry until P = ATC and firms earn zero economic profit. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition This figure shows a firm in monopolistic competition moving from short-run equilibrium to longrun equilibrium. If firms incur an economic loss, firms exit to restore the long-run equilibrium just described. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Monopolistic Competition and Efficiency Firms in monopolistic competition are inefficient and operate with excess capacity. Figure 13.3 on the next slide illustrates these propositions. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Because they product- differentiate and face a downwardsloping demand curve for their products, firms in monopolistic competition receive a marginal revenue that is less than price for all levels of output. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Firms maximize profit by setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost, so with marginal revenue less than price, marginal cost is also less than price. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition Because price equals the marginal benefit, marginal cost is less than marginal benefit. Underproduction in monopolistic competition creates deadweight loss. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition A firm’s capacity output is the output at which average total cost is at its minimum. At the long-run profit maximizing output, price equals average total cost. But recall that MR < P, which means that MC < ATC. Output and Price in Monopolistic Competition If MC < ATC, then the ATC curve is falling. With output in the range of falling ATC, output is less than capacity output. Goods are not produced at the minimum unit cost of production in the long run. Product Development and Marketing Innovation and Product Development We’ve looked at a firm’s profit-maximizing output decision in the short run and the long run of a given product and with given marketing effort. To keep earning an economic profit, a firm in monopolistic competition must be in a state of continuous product development. New product development allows a firm to gain a competitive edge, if only temporarily, before competitors imitate the innovation. Product Development and Marketing Innovation is costly, but it increases total revenue. Firms pursue product development until the marginal revenue from innovation equals the marginal cost of innovation. Production development may benefit the consumer by providing an improved product, or it may only create the appearance of a change in product quality. Regardless of whether a product improvement is real or imagined, its value to the consumer is its marginal benefit, which is the amount the consumer is willing to pay for it. Product Development and Marketing Marketing A firm’s marketing program uses advertising and packaging as the two principal methods to market its differentiated products to consumers. Firms in monopolistic competition incur heavy marketing and advertising expenditures to enhance the perception of quality differences between their product and rival products. These costs make up a large portion of the price for the product. Product Development and Marketing Figure 13.4 shows estimates of the percentage of sale price for different monopolistic competition markets. Cleaning supplies and toys top the list at almost 15 percent. Product Development and Marketing Selling Costs and Total Costs Selling costs, like advertising expenditures, fancy retail buildings, etc. are fixed costs. Average fixed costs decrease as production increases, so selling costs increase average total costs at any given level of output but do not affect the marginal cost of production. Selling efforts such as advertising are successful if they increase the demand for the firm’s product. Product Development and Marketing Advertising costs might lower the average total cost by increasing equilibrium output and spreading their fixed costs over the larger quantity produced. Here, with no advertising, the firm produces 25 units of output at an average total cost of $170. Product Development and Marketing With advertising, the firm produces 130 units of output at an average total cost of $160. The advertising expenditure shifts the average total cost curve upward, but the firm operates at a higher output and lower ATC than it would without advertising. Product Development and Marketing Advertising might also decrease the markup. Figure (a) shows that with no advertising, the demand for a firm’s output is not very elastic and its markup is large. Profits are approximately (55-35)x75=1500 Product Development and Marketing Figure (b) shows that if all firms advertise, the demand for a firm’s output becomes more elastic. The firm produces a larger quantity, its price falls, and its markup shrinks. However, its profits fall. On the other hand, if all firms do not advertise, then demand may stay relatively inelastic and profits would most likely rise with advertising. However, in the long run all firms will need to advertise in order to survive. Product Development and Marketing Therefore, advertising can increase a firm’s demand and profits in the short run only. Economic profit leads to entry, which decreases the demand for each firm’s product in the long run. And most firms advertise so each firm’s demand becomes more elastic and profits will fall in the long run, even if each firm’s output increases. To the extent that advertising and selling costs provide consumers with information and services that they value more highly than their cost, these activities are efficient. Oligopoly An oligopoly is a market in which a small number of producers compete with each other. The quantity sold by any one producer depends on that producer’s price and on the other producers’ prices and quantities sold. What is Oligopoly? Examples of Oligopoly The red bars refer to the 4 largest firms. Green is the next 4. Blue is the next 12. The numbers are the HHI. Models of Oligopoly A variety of models have been developed to explain the determination of price and quantity in oligopoly markets. No one theory explains the behavior we see in different oligopoly markets. The most recent approach to studying oligopoly behavior is game theory Oligopoly Games Game theory is a tool for studying strategic behavior, which is behavior that takes into account the expected behavior of others and the mutual recognition of interdependence. What Is a Game? All games share four features: Rules Strategies Payoffs Outcome Oligopoly Games The Prisoners’ Dilemma The prisoners’ dilemma game illustrates the four features of a game. The rules describe the setting of the game, the actions the players may take, and the consequences of those actions. In the prisoners’ dilemma game, two prisoners (Art and Bob) have been caught committing a petty crime. Each is held in a separate cell and cannot communicate with the other. Oligopoly Games Each is told that both are suspected of committing a more serious crime. If one of them confesses, he will get a 1-year sentence for cooperating while his accomplice get a 10-year sentence for both crimes. If both confess to the more serious crime, each receives 3 years in jail for both crimes. If neither confesses, each receives a 2-year sentence for the minor crime only. Oligopoly Games In game theory, strategies are all the possible actions of each player. Art and Bob each have two possible actions: Confess to the larger crime Deny having committed the larger crime Because there are two players and two actions for each player, there are four possible outcomes: Both confess Both deny Art confesses and Bob denies Bob confesses and Art denies Oligopoly Games Each prisoner can work out what happens to him— can work out his payoff—in each of the four possible outcomes. We can tabulate these outcomes in a payoff matrix. A payoff matrix is a table that shows the payoffs for every possible action by each player for every possible action by the other player. The next slide shows the payoff matrix for this prisoners’ dilemma game. Payoff Matrix Oligopoly Games Oligopoly Games If a player makes a rational choice in pursuit of his own best interest, he chooses the action that is best for him, given any action taken by the other player. If both players are rational and choose their actions in this way, the outcome is an equilibrium called Nash equilibrium—first proposed by John Nash. The following slides show how to find the Nash equilibrium. Bob’s view of the world Bob’s view of the world Art’s view of the world Art’s view of the world Equilibrium Another Example of The Prisoners’ DilemmaAdvertising Decisions Two firms, A & B, are deciding whether to devote more resources to advertising. Advertising can increase demand at both the industry (new customers for the product) and firm specific level (consumers switching from one brand to another). Advertising yields the following payoff matrix. Prisoners’ Dilemma Payoff Payoff Matrix Firm A’s Strategies Advertises Does not advertise Firm A 70 Firm A 40 Advertises Firm B’ Strategies Does not advertise Firm B 80 Firm A 100 Firm B 50 Firm B 100 Firm A 80 Firm B 90 Advertising Decisions In this case, the Nash equilibrium is that both firm’s advertise. Firm A’s payoff is 70 and Firm B’s payoff is 80. But, both firms would have been better off if neither had advertised. Firm A’s payoff would have been 80 and Firm B’s payoff would have been 90. The costs of advertising outweighed the gains for both firms. Of course, the firms could cooperate and agree not to advertise. But there is always an incentive to cheat to increase profits. It might be possible to devise a penalty system for cheating that will lead to the desired outcome. However, cooperation between the firms might cause the Justice Department to investigate possible antitrust violations. Pricing Decisions Another example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma has to do with pricing decisions. Suppose there are two firms and each must decide whether to charge a low price or a high price for their product. The profit payoff matrix is as follows. Pricing Decisions Profit Payoff Matrix Firm A’s Strategies Low Price High Price Firm A 9000 Firm A 12000 High Price Firm B’ Strategies Low Price Firm B 9000 Firm A 3000 Firm B 12000 Firm B 3000 Firm A 8000 Firm B 8000 Pricing Decisions In this case, the Nash equilibrium is that both firm’s charge low prices. However, both firms would have been better off if they had charged high prices. Their profits would have been 9000 instead of 8000. Fear of price cutting by their competitor leads them to a suboptimal solution. Of course, the firms could cooperate and agree to charge high prices. But there is always an incentive to cheat to increase profits. Also, cooperation between the firms might cause the Justice Department to investigate possible antitrust violations. It is possible to devise a pricing scheme that will lead to the desired outcome – matching lower prices of competitors. Pricing Decisions Matching Prices Target Best Buy Pricing Decisions Profit Payoff Matrix Firm A’s Strategies Low Price High Price Firm A 9000 Firm A 12000 High Price Firm B’ Strategies Low Price Firm B 9000 Firm A 3000 Firm B 12000 Firm B 3000 Firm A 8000 Firm B 8000 Other Applications of Game Theory The ideas just discussed can be used to understand a host of other real world economic situations, such as product modification price discrimination entering and leaving an industry investing in R&D (research and development)