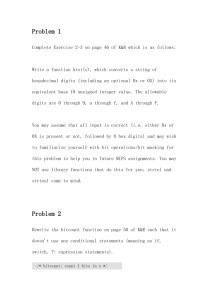

Chapter 2

advertisement

ECE369

Chapter 2

ECE369

1

Instruction Set Architecture

•

A very important abstraction

– interface between hardware and low-level software

– standardizes instructions, machine language bit patterns, etc.

– advantage: different implementations of the same architecture

– disadvantage: sometimes prevents using new innovations

•

Modern instruction set architectures:

– IA-32, PowerPC, MIPS, SPARC, ARM, and others

ECE369

2

The MIPS Instruction Set

•

•

•

•

Used as the example throughout the book

Stanford MIPS commercialized by MIPS Technologies (www.mips.com)

Large share of embedded core market

– Applications in consumer electronics, network/storage equipment,

cameras, printers, …

Typical of many modern ISAs

– See MIPS Reference Data tear-out card, and Appendixes B and E

ECE369

3

MIPS arithmetic

•

•

All instructions have 3 operands

Operand order is fixed (destination first)

Example:

C code:

a = b + c

MIPS ‘code’:

add a, b, c

(we’ll talk about registers in a bit)

“The natural number of operands for an operation like addition is

three…requiring every instruction to have exactly three operands, no

more and no less, conforms to the philosophy of keeping the

hardware simple”

ECE369

4

MIPS arithmetic

•

•

Design Principle: simplicity favors regularity.

Of course this complicates some things...

C code:

a = b + c + d;

MIPS code:

add a, b, c

add a, a, d

•

•

Operands must be registers, only 32 registers provided

Each register contains 32 bits

•

Design Principle: smaller is faster.

ECE369

Why?

5

Registers vs. Memory

•

•

•

Arithmetic instructions operands must be registers,

— only 32 registers provided

Compiler associates variables with registers

What about programs with lots of variables

Control

Input

Memory

Datapath

Processor

Output

I/O

ECE369

6

Memory Organization

•

•

•

Viewed as a large, single-dimension array, with an address.

A memory address is an index into the array

"Byte addressing" means that the index points to a byte of memory.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

...

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

8 bits of data

ECE369

7

Memory Organization

•

•

•

•

•

Bytes are nice, but most data items use larger "words"

For MIPS, a word is 32 bits or 4 bytes.

0 32 bits of data

4 32 bits of data

Registers hold 32 bits of data

32

bits

of

data

8

12 32 bits of data

...

232 bytes with byte addresses from 0 to 232-1

230 words with byte addresses 0, 4, 8, ... 232-4

Words are aligned

i.e., what are the least 2 significant bits of a word address?

ECE369

8

Instructions

•

•

Load and store instructions

Example:

C code: A[12] = h + A[8];

# $s3 stores base address of A and $s2 stores h

MIPS code:

lw $t0, 32($s3)

add $t0, $s2, $t0

sw $t0, 48($s3)

•

•

•

Can refer to registers by name (e.g., $s2, $t2) instead of number

Store word has destination last

Remember arithmetic operands are registers, not memory!

Can’t write:

add 48($s3), $s2, 32($s3)

ECE369

9

Instructions

•

Example:

C code:

g = h + A[i];

# $s3 stores base address of A and

# g,h and i in $s1,$s2 and $s4

Add $t1,$s4,$s4

t1 = 2*i

Add $t1,$t1,$t1

t1 = 4*i

Add $t1,$t1,$s3

t1 = 4*i + s3

Lw $t0,0($t1)

t0 = A[i]

Add $s1,$s2,$t0

g = h + A[i]

ECE369

10

So far we’ve learned:

•

MIPS

— loading words but addressing bytes

— arithmetic on registers only

•

Instruction

Meaning

add $s1, $s2, $s3

sub $s1, $s2, $s3

lw $s1, 100($s2)

sw $s1, 100($s2)

$s1 = $s2 + $s3

$s1 = $s2 – $s3

$s1 = Memory[$s2+100]

Memory[$s2+100] = $s1

ECE369

11

Policy of Use Conventions

Name Register number

$zero

0

$v0-$v1

2-3

$a0-$a3

4-7

$t0-$t7

8-15

$s0-$s7

16-23

$t8-$t9

24-25

$gp

28

$sp

29

$fp

30

$ra

31

Usage

the constant value 0

values for results and expression evaluation

arguments

temporaries

saved

more temporaries

global pointer

stack pointer

frame pointer

return address

Register 1 ($at) reserved for assembler, 26-27 for operating system

ECE369

12

MIPS Format

•

Instructions, like registers and words

– are also 32 bits long

–

–

•

add $t1, $s1, $s2

Registers: $t1=9, $s1=17, $s2=18

Instruction Format:

000000

op

10001

rs

10010

rt

01001

rd

00000

shamt

ECE369

100000

funct

13

Machine Language

•

•

•

•

Consider the load-word and store-word instructions,

– What would the regularity principle have us do?

– New principle: Good design demands a compromise

Introduce a new type of instruction format

– I-type for data transfer instructions

– other format was R-type for register

Example: lw $t0, 32($s2)

35

18

9

op

rs

rt

32

16 bit number

Where's the compromise?

ECE369

14

Summary

Name Register number

$zero

0

$v0-$v1

2-3

$a0-$a3

4-7

$t0-$t7

8-15

$s0-$s7

16-23

$t8-$t9

24-25

$gp

28

$sp

29

$fp

30

$ra

31

Usage

the constant value 0

values for results and expression evaluation

arguments

temporaries

instruction format op

saved

add

R 0

more temporaries

global pointer

sub

R 0

stack pointer

lw

I 35

frame pointer

sw

I 43

return address

A[300]=h+A[300]

Lw $t0,1200($t1)

Add $t0, $s2, $t0

Sw $t0, 1200($t1)

rs

reg

reg

reg

reg

rt

reg

reg

reg

reg

rd shamt funct address

reg 0 32 na

reg 0 34 na

na na na address

na na na address

# $t1 = base address of A, $s2 stores h

# use $t0 for temporary register

Op rs,rt,address

Op,rs,rt,rd,shamt,funct

Op,rs,rt,address

ECE369

35,9,8,1200

0,18,8,8,0,32

43,9,8,1200

15

Summary of Instructions We Have Seen So Far

ECE369

16

Summary of New Instructions

ECE369

17

Example

swap(int* v, int k);

{ int temp;

temp = v[k]

v[k] = v[k+1];

v[k+1] = temp;

}

swap:

sll $t0, $a1, 4

add $t0, $t0, $a0

lw $t1, 0($t0)

lw $t2, 4($t0)

sw $t2, 0($t0)

sw $t1, 4($t0)

jr $31

ECE369

18

Control Instructions

ECE369

19

Using If-Else

$s0 = f

$s1 = g

$s2 = h

$s3 = i

$s4 = j

$s5 = k

Where is 0,1,2,3 stored?

ECE369

20

Addresses in Branches

•

•

Instructions:

bne $t4,$t5,Label

beq $t4,$t5,Label

Next instruction is at Label if $t4≠$t5

Next instruction is at Label if $t4=$t5

Formats:

I

op

rs

rt

16 bit address

•What if the “Label” is too far away (16 bit address is not enough)

ECE369

21

Addresses in Branches and Jumps

• Instructions:

bne $t4,$t5,Label

beq $t4,$t5,Label

j Label

if $t4 != $t5

if $t4 = $t5

Next instruction is at Label

• Formats:

I

op

J

op

rs

rt

16 bit address

26 bit address

•

ECE369

22

Control Flow

• We have: beq, bne, what about Branch-if-less-than?

If (a<b) # a in $s0, b in $s1

slt

$t0, $s0, $s1

bne $t0, $zero, Less

# t0 gets 1 if a<b

# go to Less if $t0 is not 0

Combination of slt and bne implements branch on less than.

ECE369

23

While Loop

While (save[i] == k)

i = i+j;

# i, j and k correspond to registers

# $s3, $s4 and $s5

# array base address at $s6

Loop: add $t1, $s3, $s3

add $t1, $t1, $t1

add $t1, $t1, $s6

lw $t0, 0($t1)

bne $t0, $s5, Exit

add $s3, $s3, $s4

j

loop

Exit:

ECE369

24

What does this code do?

ECE369

25

Overview of MIPS

•

•

•

simple instructions all 32 bits wide

very structured, no unnecessary baggage

only three instruction formats

R

op

rs

rt

rd

I

op

rs

rt

16 bit address

J

op

shamt

funct

26 bit address

ECE369

26

Arrays vs. Pointers

clear1( int array[ ], int size)

{

int i;

for (i=0; i<size; i++)

array[i]=0;

}

clear2(int* array, int size)

{

int* p;

for( p=&array[0]; p<&array[size]; p++)

*p=0;

}

CPI for arithmetic, data transfer, branch type of instructions are 1, 2,

and 1 correspondingly. Which code is faster?

ECE369

27

Clear1

array in $a0

size in $a1

i in $t0

clear1( int array[ ], int size)

{

int i;

for (i=0; i<size; i++)

array[i]=0;

}

add

loop1: add

$t0,$zero,$zero # i=0, register $t0=0

$t1,$t0,$t0

# $t1=i*2

add

add

sw

addi

slt

$t1,$t1,$t1

$t2,$a0,$t1

$zero, 0($t2)

$t0,$t0,1

$t3,$t0,$a1

# $t1=i*4

# $t2=address of array[i]

# array[i]=0

# i=i+1

# $t3=(i<size)

bne

$t3,$zero,loop1 # if (i<size) go to loop1

ECE369

28

Clear2, Version 2

clear2(int* array, int size)

{

int* p;

for( p=&array[0]; p<&array[size]; p++)

*p=0;

}

loop2:

Array and size

to registers $a0 and $a1

add

$t0,$a0,$zero

# p = address of array[0]

add

add

add

sw

addi

slt

bne

$t1,$a1,$a1

$t1,$t1,$t1

$t2,$a0,$t1

$zero,0($t0)

$t0,$t0,4

$t3,$t0,$t2

$t3,zero,loop2

# $t1 = size*2

# $t1 = size*4 Distance of last element

# $t2 = address of array[size]

# memory[p]=0

# p = p+4

# $t3=(p<&array[size])

# if (p<&array[size]) go to loop2

29

ECE369

Array vs. Pointer

loop1:

add

add

add

add

sw

addi

slt

bne

add

loop2:

add

add

add

sw

addi

slt

bne

$t0,$zero,$zero

$t1,$t0,$t0

$t1,$t1,$t1

$t2,$a0,$t1

$zero, 0($t2)

$t0,$t0,1

$t3,$t0,$a1

$t3,$zero,loop1

# i=0, register $t0=0

# $t1=i*2

# $t1=i*4

# $t2=address of array[i]

# array[i]=0

# i=i+1

# $t3=(i<size)

# if (i<size) go to loop1

$t0,$a0,$zero

7 instructions

inside loop

# p = address of array[0]

$t1,$a1,$a1

$t1,$t1,$t1

$t2,$a0,$t1

$zero,0($t0)

# $t1 = size*2

# $t1 = size*4

4 instructions

# $t2 = address of array[size] inside loop

# memory[p]=0

$t0,$t0,$4

$t3,$t0,$t2

$t3,zero,loop2

# p = p+4

# $t3=(p<&array[size])

# if (p<&array[size]) go to loop2

ECE369

30

Summary

ECE369

31

Other Issues

•

More reading:

support for procedures

linkers, loaders, memory layout

stacks, frames, recursion

manipulating strings and pointers

interrupts and exceptions

system calls and conventions

•

Some of these we'll talk more about later

•

We have already talked about compiler optimizations

ECE369

32

Elaboration

Name Register number

$zero

0

$v0-$v1

2-3

$a0-$a3

4-7

$t0-$t7

8-15

$s0-$s7

16-23

$t8-$t9

24-25

$gp

28

$sp

29

$fp

30

$ra

31

Usage

the constant value 0

values for results and expression evaluation

arguments

temporaries

saved

more temporaries

global pointer

stack pointer

frame pointer

return address

What if there are more than 4 parameters for a function call?

Addressable via frame pointer

References to variables in the stack have the same offset

ECE369

33

What is the Use of Frame Pointer?

Variables local to procedure do not fit in registers !!!

ECE369

34

Nested Procedures,

function_main(){

function_a(var_x);

:

return;

}

function_a(int size){

function_b(var_y);

:

return;

}

function_b(int count){

:

return;

}

/* passes argument using $a0 */

/* function is called with “jal” instruction */

/* passes argument using $a0 */

/* function is called with “jal” instruction */

Resource Conflicts ???

ECE369

35

Stack

• Last-in-first-out queue

• Register # 29 reserved as stack

pointer

• Points to most recently

allocated address

• Grows from higher to lower

address

• Subtracting $sp

• Adding data – Push

• Removing data – Pop

ECE369

36

Function Call and Stack Pointer

jr

ECE369

37

Recursive Procedures Invoke Clones !!!

int fact (int n) {

if (n < 1 )

return ( 1 );

else

return ( n * fact ( n-1 ) );

}

Registers $a0 and $ra

“n” corresponds to $a0

Program starts with the label of the procedure “fact”

How many registers do we need to save on the stack?

ECE369

38

Factorial Code

200 fact:addi

204

sw

sw

L1:

236

240

$sp, $sp, -8 #adjust stack for 2 items

$ra, 4($sp) #save return address

$a0, 0($sp) #save argument n

slti

beq

$t0, $a0, 1

# is n<1?

$t0, $zero, L1 # if not go to L1

addi

addi

jr

$v0, $zero, 1

$sp, $sp, 8

$ra

addi

jal

$a0, $a0, -1

fact

lw

lw

addi

mult

jr

:

100 fact(3)

104 add ….

#return result

#pop items off stack

#return to calling proc.

#decrement n

# call fact(n-1)

$a0, 0($sp) # restore “n”

$ra, 4($sp) # restore address

$sp, $sp,8

# pop 2 items

$v0,$a0,$v0 # return n*fact(n-1)

$ra

# return to caller

ECE369

ra = 104

a0= 3

sp= 40

vo=

int fact (int n) {

if (n < 1 )

return ( 1 );

else

return ( n * fact ( n-1 ) );

}

39

Assembly to Hardware Example

k is stored in $t0;

3 stored in $t2;

int i;

int k = 0;

add

for (i=0; i<3; i++){

add

k = k + i + 1;

addi

}

loop: add

k = k/2;

addi

addi

slt

bne

srl

i is stored in $t1

$t3 used as temp

$t0,$zero,$zero

$t1,$zero,$zero

$t2,$zero,3

$t0,$t0,$t1

$t0,$t0,1

$t1,$t1,1

$t3,$t1,$t2

$t3,$zero,loop

$t0,$t0,1

ECE369

# k=0, register $t0=0

# i=0, register $t1=0

# $t2=3

#k=k+i

#k=k+1

# i=i+1

# $t3= (i<3)

# if (i<3) go to loop

#k=k/2

40

Assembly to Hardware Example

add

add

addi

loop: add

addi

addi

slt

bne

$t0,$zero,$zero R-Type

$t1,$zero,$zero R-Type

$t2,$zero,3

I-Type

$t0,$t0,$t1

R-Type

$t0,$t0,1

I-Type

$t1,$t1,1

I-Type

$t3,$t1,$t2

R-Type

$t3,$zero,loop I-Type

srl

$t0,$t0,1

Instruction Types?

R-Type

R

op

rs

rt

rd

I

op

rs

rt

16 bit address

ECE369

shamt

funct

41

How do we represent in machine language?

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

funct

0:

add

$t0,$zero,$zero 000000_00000_00000_01000_00000_100000

4:

add

$t1,$zero,$zero 000000_00000_00000_01001_00000_100000

8:

addi

$t2,$zero,3

001000_00000_01010_0000000000000011

12: loop:

add

$t0,$t0,$t1

000000_01000_01001_01000_00000_100000

16:

addi

$t0,$t0,1

001000_01000_01000_0000000000000001

20:

addi

$t1,$t1,1

001000_01001_01001_0000000000000001

24:

slt

$t3,$t1,$t2

000000_01001_01010_01011_00000_101010

28:

bne

$t3,$zero,loop

000101_00000_01011_1111111111111011

32:

srl

$t0,$t0,2

000000_00000_01000_01000_00001_000010

6 bits

R

I

5 bits

5 bits

5 bits

5 bits

6 bits

shamt

funct

op

rs

rt

rd

op

rs

rt

16 bit address

ECE369

PC+4+BR Addr

- 5

$t0 is reg 8

$t1 is reg 9

$t2 is reg 10

$t3 is reg 11

42

How do we represent in machine language?

loop:

add

$t0,$zero,$zero

add

$t1,$zero,$zero

addi

$t2,$zero,3

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

funct

Instruction Memory

0

000000_00000_00000_01000_00000_100000

4

000000_00000_00000_01001_00000_100000

8

001000_00000_01010_0000000000000011

add

$t0,$t0,$t1

addi

$t0,$t0,1

12

000000_01000_01001_01000_00000_100000

addi

$t1,$t1,1

16

001000_01000_01000_0000000000000001

20

001000_01001_01001_0000000000000001

24

000000_01001_01010_01011_00000_101010

28

000101_00000_01011_1111111111111011

32

000000_00000_01000_01000_00001_000010

slt

$t3,$t1,$t2

bne

$t3,$zero,loop

srl

$t0,$t0,2

ECE369

43

Representation in MIPS Datapath

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

Instruction Memory

0

000000_00000_00000_01000_00000_100000

4

000000_00000_00000_01001_00000_100000

8

001000_00000_01010_0000000000000011

12

000000_01000_01001_01000_00000_100000

16

001000_01000_01000_0000000000000001

20

001000_01001_01001_0000000000000001

24

000000_01001_01010_01011_00000_101010

28

000101_00000_01011_1111111111101100

32

000000_00000_01000_01000_00001_000010

funct

Name Register number

$zero

0

$v0-$v1

2-3

$a0-$a3

4-7

$t0-$t7

8-15

$s0-$s7

16-23

$t8-$t9

24-25

$gp

28

$sp

29

$fp

30

$ra

31

ECE369

Usage

the constant value 0

values for results and expression evaluation

arguments

temporaries

saved

more temporaries

global pointer

stack pointer

frame pointer

return address

44

Big Picture

ECE369

45

Compiler

ECE369

46

Addressing Modes

ECE369

47

Our Goal

add $t1, $s1, $s2 ($t1=9, $s1=17, $s2=18)

– 000000 10001 10010 01001 00000

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

ECE369

100000

funct

48

Assembly Language vs. Machine Language

•

•

•

•

Assembly provides convenient symbolic representation

– much easier than writing down numbers

– e.g., destination first

Machine language is the underlying reality

– e.g., destination is no longer first

Assembly can provide 'pseudoinstructions'

– e.g., “move $t0, $t1” exists only in Assembly

– would be implemented using “add $t0,$t1,$zero”

When considering performance you should count real instructions

ECE369

49

Summary

•

•

•

Instruction complexity is only one variable

– lower instruction count vs. higher CPI / lower clock rate

Design Principles:

– simplicity favors regularity

– smaller is faster

– good design demands compromise

– make the common case fast

Instruction set architecture

– a very important abstraction indeed!

ECE369

50