STROKE IN THE

YOUNG

Chair : Prof. Dr. B. Jayakumar

INTRODUCTION

• Young stroke is stroke occurring

between 15 and 45 years of age

• Differential diagnosis for potential

etiologies is broader

• Even after extensive investigations,

the cause may remain elusive in 2050% cases

• Prognosis depends on the underlying

factor

• Responsible for about 5% of all cases

of stroke

• Incidence is much higher in

developing countries like India.

• Above the age of 30 years stroke is

more common in males whereas

below that female predominance is

seen.

Etiology of young stroke

ISCHEMIC

• Large artery disease

– Premature atherosclerosis

– Dissection (spontaneous or traumatic)

– Inherited metabolic diseases (homocysteinuria,

Fabry’s disease, pseudoxanthoma elasticum,

MELAS syndrome)

– Fibromuscular dysplasia

– Vasculitis

– Moyamoya disease

– Radiation

– Toxic (drug induced)

• Small vessel disease

– Vasculopathy (infectious, non infectious,

microangiopathy)

• Cardioembolic disease

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Rheumatic heart disease

Congenital heart disease

Arrhythmias

Bacterial and non-bacterial endocarditis

Mitral valve prolapse

Patent foramen ovale

Atrial myxoma

Cardiac surgeries and procedures

• Hematologic disease

– Sickle cell disease

– Leukemia

– Hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid

antibody syndromes, deficiency of

antithrombin III or protein S or C, resistance

to activated protein C, increased factor VIII)

– Disseminated intravascular coagulation

– Thrombocytosis

– Polycythemia vera

– Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

– Venous occlusion

• Migraine

• HEMORRHAGIC

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage

– Cerebral aneurysm

• Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

– Arteriovenous malformation

– Neoplasm (primary central nervous system,

metastatic, leukemia)

– Hematological disorders (sickle cell disease,

neoplasm, thrombocytopenia)

– Moyamoya disease

– Drug use (warfarin, amphetamines, cocaine,

phenylpropanolamine)

– Iatrogenic (peri-procedural)

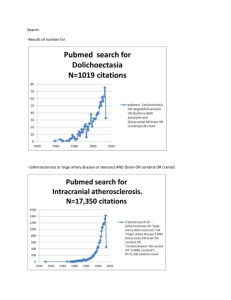

Premature atherosclerosis

• Premature atherosclerosis is the

single most important cause of

stroke as age advances

• Incidence is 7-30% below the age of

50 years.

• It is presumed in all undiagnosed

cases with more than two risk

factors.

• Risk factors for atherosclerosis

– Male sex

– Systemic hypertension

– Diabetes mellitus

– Dyslipidemia (low HDL cholesterol,

hypertriglyceridemia)

– Cigarette smoking

– Alcohol abuse

– Ischemic heart disease

– Recent infection

– Oestrogen related stroke including oral

contraceptives

NON ATHEROSCLEROTIC

VASCULOPATHIES

• Cervicocephalic arterial dissections

• Traumatic cerebrovascular disease

• Radiation-induced vasculopathy

• Moyamoya disease

• Fibromuscular dysplasia

• Vasculitis

• Migrainous infarction

Cerviocephalic arterial

dissections

• Subintimal penetration of blood with

subsequent longitudinal extension of

the hematoma between its layers

• Common sites

– Extracranial segment of internal carotid

artery

– Extracranial vertebral arteries

• Recurrence rate is 1%, more in

young and in those with positive

family history

Causes

• Spontaneous

• Secondary

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Blunt or penetrating trauma

Fibromuscualar dysplasia

Ehlers’ Danlos syndrome type IV

Marfan’s syndrome

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Coarctation of aorta

Menke’s disease

α1-antitrypsin deficiency

Cystic medial degeneration

Osteogenesis imperfecta

Adult polycystic kidney disease

Homocystinuria

Luteic arteritis

• Dissection results in ischemic

symptoms due to arterial occlusion

or secondary embolism

• Diagnosis

– Arteriography – Elongated, irregular,

narrow column of dye, ‘string sign’

– High resolution MRI

– MR angiography

– CT angiography

– Doppler ultrasound of the neck

especially for carotid diseection

Internal

carotid artery

dissection

• Treatment

– Anticoagulation with heparin should be

started followed by warfarin therapy for

3–6 months

– Antiplatelet therapy

– Surgical therapy indicated in the

presence of pseudoaneurysms and if

there is no response to medical

treatment

– Anticoagulation should be withheld in

intracranial dissection since there is a

risk of subarachnoid haemorrhage

Trauma

• Blunt or penetrating trauma can produce

arterial dissection, rupture, thrombosis,

pseudoaneurysm formation and AV fistula.

• Can occur during sports, violent coughing,

vigorous nose blowing, neck manipulation,

anesthesia administration etc.

• Cervical rotation or extension compresses

cervical carotid artery against transverse

processes of upper cervical vertebra

• Angiography and surgical repair is the

treatment.

Radiation vasculopathy

• Accelerated atherosclerosis occurs

especially in those with dyslipidemia

• Radiation results in damage to the

endothelial cells producing

complications months to years later

• Lesions occur at unusual sites

• The amount of damage depends on

– Radiation dose

– Age at the time of therapy

Moyamoya disease

• Moyamoya is a Japanese word meaning

‘puff of smoke’

• It is a chronic progressive non-amyloid

non-atherosclerotic, non-inflammatory

occlusive arteriopathy of unknown cause.

• Characterized by progressive bilateral

stenosis of distal ICA extending to

proximal ACA and MCA with involvement

of circle of Willis and development of

extensive collateral network

(parenchymal, leptomeningeal or

transdural) at the base of the brain like a

puff of smoke. Intracranial aneurysms are

seen, especially in posterior circulation.

• Pathology

– Fibrocellular intimal thickening, smooth

muscle proliferation and increased

elastin accumulation leading to stenosis

of suprasellar intracranial ICA

– Thinning of media with tortuous and

multilayered internal elastic lamina

• Clinical features

– TIA, seizures, headache, movement

disorders, mental deterioration, cerebral

infarction , intracranial hemorrhage

– TIAs are precipitated by crying, blowing

and hyperventilation

• Bimodal age distribution is seen

– First decade – ischemic events more common

– Fourth decade – Hemorrhagic commoner

• Diagnosis is established by arteriography

• Suzuki’s six arteriographic changes

– Stenosis of carotid fork

– Initial appearance of moyamoya vessels at the

base of brain

– Intensification of moyamoya vessels

– Minimization of moyamoya vessels

– Reduction of moyamoya vessels

– Disappearance of the vessels

MCA block with multiple collateral

moyamoya vessels

Treatment

• Ischemic Moyamoya

– Platelet antiaggregants, vasodilators,

calcium channel blockers and

corticosteroids have been tried.

– Anticoagulants are not useful

– Surgical revascularization techniques

like superficial temporal to MCA

anastamosis have produced good

results.

• Hemorrhagic Moyamoya

– No established therapy to prevent

rebleed

Fibromuscualar dysplasia

• Segmental, non-atheromatous, dysplastic,

non-inflammatory angiopathy

• Commonly affects young and middle aged

women

• White race more affected

• Etiology

– Unknown

– May be related to immunological mechanisms,

estrogenic effects, α1-antitrypsin deficiency

– Familial association seen

• Renal arteries most commonly involved.

Cervicocephalic involvement in less than

1%

• Most often extracranial carotids involved

• Bilateral in two thirds

• Four histologic types

–

–

–

–

Intimal hyperplasia

Medial hyperplasia

Medial fibroplasia: Commonest

Perimedial dysplasia

• Most of the patients are asymptomatic

• Diagnosis

– Cervical angiography

– ‘String of beads’ appearance in medial

fibroplasia

• Treatment

– Benign natural history

– Platelet antiaggregants used

– Surgical intervention seldom needed

Types of fibromuscular dysplasia

Cerebral autosomal dominant

arteriopathy with subcortcal infarcts

and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL)

• Familial nonarteriosclerotic, nonamyloid

microangiopathy

• Characteristic features

– Migraine with aura (CADASILM)

– Recurrent subcortical ischemic strokes from

mid-adulthood

– Pseudobulbar palsy, cognitive decline,

subcortical dementia

– Early white matter hyperintensities in MRI

• Genetics

– Missense mutations or small deletions

in Notch 3 gene on chromosome 19q12

– Codes for transmembrane receptor

Notch 3

• Granular eosinophilic material

deposited in arterial walls, including

dermal arteries

Binswanger disease

• Widespread degeneration of cerebral

white matter of vascular causation

• Associated with hypertension,

atherosclerosis of small blood vessels

and multiple strokes.

• Radiological picture of leucoareosis –

less intense appearance of

periventricualar tissues in chronically

hypertensive patients

Mitochondrial myopathy, lactic

acidosis and strokes (MELAS)

• Mitochondrial disorder which may manifest

at any age,usually in childhood

• Clinical features

–

–

–

–

Proximal myopathy, exercise intolerance

Recurrent migraine-type headaches

Hemiparesis, hemianopsia or cortical blindness

Precipitated by exercise or infection

• Serum and CSF lactate concentrations are

elevated

Migrainous infarction

• Migraine commonly affects women and

starts during childhood or adolescence

• Rare association of migraine and ischemic

stroke seen in young women particularly

below 35 years of age.

• Pathogenesis is not completely known

• Migrainous infarctions are mostly cortical

and involve PCA territory

• Usually there is gradual build up of

unilateral throbbing headaches with visual

phenomena occurring in both visual fields

simultaneously, in one of which the visual

loss becomes permanent.

• Diagnostic critreria

– Definite diagnosis of migraine with aura in the

past

– One or more of the migrainous aura symptoms

must be present and not fully reversed within

7 days from the onset, with neuroimaging

confirmation of ischemic infarction

– Clinical manifestations should be those typical

of previous attacks

– Other causes of infarction should be excluded

• Definite migrainous infarction – all criteria

satisfied

• Possible – only some criteria satisfied

• Increases risk for recurrent stroke

CEREBRAL VASCULITIDES

• Infectious vasculitis

– Bacterial, fungal, parasitic, spirochetal, viral,

rickettsial, mycobacterial

• Necrotising vasculitis

– Classic polyateritis nodosa, Wegener’s

granulomatosis, allergic angitis and

granulomatosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis

• Vasculitis associated with collagen

vascular disease

– SLE, Rheumatoid arthritis, Scleroderma,

Sjogren’s syndrome

• Giant cell arteritides

– Takayasu’s arteritis, temporal arteritis

• Vasculitis associated with other systemic

diseases

– Behcet’s disease, Ulcerative colitis,

Sarcoidosis, Relapsing polychondritis,

Kohlmeier-Degos disease

• Hypersensitivity vasculitis

– Henoch-Schonlein’s purpura, Drug-induced

vasculitis, Essential mixed cryoglobulinemia

• Miscellaneous

– Vasculitis associated with neoplasia and

radiation, Cogan’s syndrome, Dermatomysoitis

polymyositis, X-linked lymphoproliferative

syndrome, TAO, Kawasaki’s syndrome, Primary

central nervous system vasculitis

• Inflammatory vasculitis should be

considered in

– Young patients with stroke

– Recurrent strokes

– Stroke with encephalopathic features

– Stroke with fever

– Multifocal neurological events

– Mononeuritis multiplex, palpable

purpura or abnormal urinary sediment

• Diagnosis usually requires

confirmation with arteriography or

biopsy

Meningovascular syphilis

• Patients usually have prodromal

symptoms

• Vasculitis can cause cerebral

infarctions, commonly in MCA

territory or spinal cord infarction.

• May be associated with headache,

meningismus, mental status

abnormalities or cranial nerve

abnormalities.

• Diagnosis

– CSF study reveals lymphocytic

pleocytosis, elevated protein control and

positive VDRL test

• Treatment

– Aqueous Penicillin G x 10-14 days

• Luteic aneurysms of the ascending

aorta can extend to the root of great

vessels causing stroke

Neurotuberculosis

• Usually affects basilar meninges resulting

in basilar meningitis which traps 3, 4 and

6 cranial nerves causing their palsy.

Basilar arteriolitis commonly involves the

penetrating branches of ACA, MCA or PCA

• Risk factors include alcoholism, substance

abuse, corticosteroid use or HIV

• CSF study shows increased protein and

decreased glucose levels and lymphocytic

and mononuclear pleocytosis. 10-20% of

the CSF smears show AFB.

HIV/AIDS

• Cerebral infarction on AIDS can

result from

– Vasculitis, meningovascular syphilis,

varicella-zoster virus vasulitis,

opportunistic infections, infective

endocarditis, aneurysmal dilatation of

major cerebral arteries, nonbacterial

thrombotic endocarditis, aPL antibodies,

or other hypercoagulable states,

hyperlipidemia induced by protease

inhibitors, HIV-1 related malignancy,

cancer chemotherapy and TTP.

• Other infectious agents are varicella

zoster, coxsackie 9 virus, California

encephalitis, mumps paramyxovirus,

hepatitis C virus, Mycoplasma

pneumoniae, Borrelia burgdorferi,

Rickettsia typhi, cat-scratch disease,

Trichinella infection, cysticercus of

Taenia solium and free living amoeba

Takayasu’s arteritis

• Chronic inflammatory arteriopathy of

aorta, its major branches and

pulmonary artery

• More common in women

• Probable immune mechanism

• Slow progression of stenosis,

occlusion, aneurysmal dilatation and

coarctation of the involved vessels

• Two phases

– Acute or prepulseless phase – nonspecific systemic symptoms

– Occlusive phase – multiple arterial

occlusions

• Neurological symptoms usually result

from CNS or retinal ischemia due to

stenosis or occlusion of the aortic

arch and arch vessels, or arterial

hypertension resulting from

coarctation of aorta or renal artery

stenosis

• Diagnosis

– MR angiography

– Aortogram

• Treatment

– In active disease, treatment is with oral

glucocorticoids; cyclophosphamide,

azathiprine or methotrexate used rarely

– Surgical treatment of severely stenotic

vessels

Drug induced vasculitis

• Drugs implicated

– Amphetamines, cocaine, phencyclidine,

phenylpropanolamine, pentazocine with

pyribenzamine, heroin, anabolic steroids and

glue sniffing.

• Mechanisms

– Foreign body embolization, vasculitis,

vasospasm, acute onset of arterial

hypertension or hypotension, endothelial

damage, accelerated atherosclerosis, hyper or

hypocoagulability, cardiac arrhythmias,

emboism from MI or AIDS.

CARDIOGENIC EMBOLISM

• High embolic potential

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Rheumatic mitral valve

Acute myocardial infarction

Infective endocarditis

Mechanical prosthetic valves

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Cardiac tumours

Cardiac arrhythmias – Atrial fibrillation

• Other causes

– Mitral valve prolapse

– Mitral annulus calcification

– Aortic valve calcification

–

–

–

–

–

Non bacterial thrombotic endocarditis

Filamentous strands of mitral valve

Giant Lambl’s excresences

Aneurysms of Sinus of Valsalva

Intracardiac defects with paradoxical embolism

• Patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, atrial

septal defect

– Cyanotic congenital heart disease

– Iatrogenic embolism

• Cavopulmonary anastamosis, coronary artery bypass

grafting, pacing, heart transplantation, artificial

hearts, cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, balloon

angioplasty, ventricular support devices,

extracorporeal membrane oxygenator

• Cardiac sources account for 15 to 20% of all

ischemic strokes.

• The emboli usually consist of platelet, fibrin,

platelet-fibrin, calcium, microorganisms, or

neoplastic fragments.

• Cardioembolic cerebral infarcts – large, multiple,

bilateral, wedge shaped

• Features of cardioembolic stroke

– Worse at onset, fast recovery

– Presence of Wernicke’s aphasia, homonymous

hemianopia, ideomotor apraxia

– Involvement of posterior division of MCA, ACA or

cerebellar involvement

– Involvement of multiple vascular territories

– Hemorrhagic component of the infarction

• Acute myocardial infarction

– 1% of patients with acute MI have

embolic stroke

– LV thrombi are commonly associated

with recent anterior wall transmural MI

– Usually embolism occurs within first 3

months, 85% within 4 weeks

– Decreased ejection fraction –

independent predictor of risk of

embolism

– There is more chance of embolism

following thrombolysis with tpA

• Dilated cardiomyopathy

– Akinesia of the chambers produces

stasis of blood and thrombus formation

– Associated LV failure and atrial

fibrillation increase the risk

– 18% of the non- anticoagulated patients

develop embolism

• Mitral stenosis

– Rheumatic mitral stenosis associated

with atrial fibrillation has high potential

for embolisation. 9-14% have systemic

emboli of which 60–75% have cerebral

ischemia.

• Endocarditis

– Infective endocarditis – vegetations may

cause systemic (left sided) or pulmonary (right

sided) embolism. If vegetations are detectable

by transthoracic echocardiogram, there is

increased risk of embolism.

– Non bacterial thrombotic endocarditis –

multiple small sterile thrombotic vegetations

occur commonly involving the mitral and aortic

valves

– Prosthetic valves – mechanical valves in

mitral position are more prone. Filamentous

strands attached to the mitral valve concede

increased risk.

• Atrial fibrillation

– More common in older adults

– Risk for AF and embolism increases with

age

– High risk for embolism exists with

rheumatic AF and AF in hyperthyroidism

• Sick sinus syndrome

– Maximum risk is associated with

bradytachyarrhythmias, LA spontaneous

echocardiographic contrast, and

decreased atrial ejection force

• Intracardiac tumours

– Atrial myxomas are the commonest tumours in

adults. Embolic complications are the

presenting symptom in one-third of patients.

Peripheral ad multiple cerebral arterial

aneurysms are remote associations.

– Cardiac rhabdomyomas and mitral valve

fibroelastomas are rarely associated with

embolism.

• Congenital heart disease

– Common cause of stroke in children.

– Risk is increased with arterial hypertension,

atrial fibrillation, history of phlebotomy and

microcytosis.

– Low Hb is associated with arterial stroke and

high Hb with cerebral venous thrombosis.

• Paradoxical embolism

– Higher rate of cerebral ischemia is reported in

persistent foramen ovale and atrial septal

aneurysms.

– A demonstrable source of embolism should be

present.

– Antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulant thearapy,

transcatheter or surgical closure of PFO is the

treatment.

• Spontaneous echo cardiographic contrast

– Associated with elevated fibrinogen levels and

plasma viscosity and is a potential risk factor

for stroke

• Post operative

– Causes

• Hypoperfusion

• Ventricular thrombi

• Emboli

– Posterior circulation stroke is more

common after cardiac catheterisation

INHERITED AND

MISCELLANEOUS DISORDERS

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Homocystinuria

Fabry’s disease

Marfan’s syndrome

Ehler-Danlos’ syndrome

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Sneddon’s syndrome

Rendu-Osler-Weber’s syndrome

Neoplastic angioendotheliomatoisis

Susac’s syndrome

• Eales’ disease

• Reversible cerebral segmental

vasoconstriction

• Hypereosinophilic syndrome

• Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

• Coils and kinks

• Arterial dolichoectasia

• Complications of coarctation of aorta

• Air, fat, amniotic fluid, bone marrow, and

foreign particle embolism

Homocystinuria

• Inborn error of amino acid metabolism.

• Any of the three enzymes deficient

– Cystathionine β-synthetase

– Homocysteine methyl transferase

– Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase

• This leads to accumulation of

homocysteine in the blood – resulting in

endothelial injury and premature

atherosclerosis.

• Elevated levels of homocysteine is an

independent risk factor for development of

cerebrovascular disease, coronary and

peripheral arterial occlusive disease.

Homocysteine metabolism

• Clinical features

– Marfanoid habitus, malar flush, liveo

reticularis, ectopia lentis, myopia, glaucoma,

optic atrophy, optic atrophy, psychiatric

manifestations, mental retardation, spasticity,

seizures, osteoporosis and a propensity for

intracranial arterial or venous thrombosis

• Homocysteine levels may be reduced by

administration of folic acid, with

pyridoxine and vitamin B12, choline,

betaine, estrogen and N-acetyl cysteine.

Fabry’s disease

• X-linked disorder of glycosphingolipid

metabolism

• Deficient lysosomal α-galactosidase

activity

• Ceramide trihexosidase accumulate in the

endothelial and smooth muscle cells

• Clinical features

– Painful peripheral neuropathy, hypertension,

cardiomegaly, renal dysfuction, autonomic

dysfunction, corneal opacifications

– Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum

Marfan’s syndrome

• Autosomal dominant

• Quantitative and qualitative defects of

fibrillin

• Variety of skeletal, ocular and

cardiovascular manifestations

• Cystic medial necrosis of the aortic

segments occur

• Dilatation of the aortic root dissection of

the ascending aorta ischemia of brain,

spinal cord and peripheral nerves

• Saccular intracranial aneurysms or

dissection of the carotid artery can occur

• Annual echocardiograms should be done

Ehler-Danlos’ syndrome

• Inherited connective tissue disorder

• Characterized by hyperextensibility of

skin, hypermobile joints and vascular

fragility

• Arterial complications occur predominantly

with type IV disease

• Complications include arterial dissections,

arteriovenous fistulae and aneurysms.

• Arteriography should be avoided if

possible.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

• Inherited disorder of elastic tissue

• Clinical features

– Loose skin, orange-yellowish papules of

intertriginous areas, arterial

hypertension, angiod streaks, retinal

hemorrhages, arterial occlusive disease

and arterial dissection.

• High risk for arterial occlusion –

coronary artery disease and stroke.

• Women should avoid estrogens

Sneddon’s syndrome

• Unknown etiology

• Frequent correlation with hypertension,

smoking and OCP

• Occurs in young women

• Charaterized by widespread livedo

reticularis and ischemic cerebrovascular

infarcts in the carotid artery territory

• Histology reveals perivascular lymphocytic

infiltration on the skin arteries with

proliferation of smooth muscle fibres on

the internal elastic lamina without

inflammation.

Atheromatous emboli

• Cholesterol embolisation usually occurs

following manipulation of an

atherosclerotic aorta during

catheterisation or surgery.

• Patient may present with TIAs, strokes,

retinal embolism, pancreatitis, renal

failure, livedo reticualris and purple toes.

• Patients have eosinophilia, anemia,

elevated ESR and elevated serum

amylase.

• Anticoagulation should be avoided.

Air embolism

• Accidental introduction of air into systemic

circulation can occur during surgical

procedures and scuba diving.

• Usually causes cerebral and retinal

ischemia

• Symptoms include seizures and multifocal

neurological findings such as cerebral

edema, confusion, memory loss and

coma.

• CT scan can visualize gaseous bubbles.

• Treatment includes resuscitative

measures, placement in left lateral

position, inotropic agents, anticonvulsants,

anti-edema agents and hyperbaric agents.

HYPERCOAGULABLE

DISORDERS

• Primary hypercoagulable states

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Antithrombin III deficiency

Protein C deficiency

Protein S deficiency

Activated protein C resistance

Prothrombin G20210 mutation

Afibrinogenemia

Hypofibrinogenemia

Hypoplasminogenemia

Plasminogen activators deficiency

Lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin

antibodies

• Secondary hypercoagulable states

– Malignancy

– Pregnancy/Puerperium

– Oral contraceptive use/ Other hormonal

treatments

– Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

– Nephrotic syndrome

– Polycythemia vera

– Essential thrombocythemia

– Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

– Diabetes mellitus

– Heparin induced thrombocytopenia

– Homocysteinuria

– Sickle cell disease

– Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

– Chemotherapeutic agents

• Inherited thrombophilias suspected if

–

–

–

–

Recurrent episodes of deep venous thrombosis

Recurrent pulmonary emboli

Family history of thrombotic events

Unusual sites of venous (mesenteric, portal or

cerebral) or arterial thrombosis

– Thrombotic events in childhood, adolescence

or early adulthood

• More than half of the events occur

spontaneously

• Risk is increased with additional risk

factors like pregnancy, surgery, trauma or

OCP

Coagulation cascade

Antithrombin III deficiency

• Autosomal dominant inheritance

• Three classes of inherited deficiency

– Classic or type I – decreased immunological

and biological activity of antithrombin III

– Type II – low biological activity, normal

immunological activity

– Type III – normal activity in the absence of

heparin, but reduced in heparin dependent

assays

• Acquired deficiency can occur in acute

thrombosis and DIC

• A normal level of AT-III during an

acute event excludes primary

deficiency.

• Treatment

– In acute thrombosis – Heparin with or

without AT III concentrate

– Recurrent thrombosis – Long term

warfarin therapy to keep INR at 2 - 3

Protein C deficiency

• Autosomal dominant inheritance

– Homozygous – Purpura fulminans neonatalis

– Heterozygous – Recurrent thrombosis

especially venous

• Acquired form

– Administration of L-aparaginase, warfarin, liver

disease, DIC, postoperatively, bone marrow

transplantation and ARDS

• Assays should be done after discontinuing

anticoagulation for at least a week.

• Initial treatment with heparin followed by

incremental doses of warfarin ( to avoid

skin necrosis)

Protein S deficiency

• Exists in free form (40%) and bound to

binding proteins

• Autosomal dominant inheritance, patients

prone for recurrent thromboembolism

• Acquired deficiency

– Pregnancy, acute thromboembolic episodes,

DIC, nephrotic syndrome, SLE, OCP,

anticoagulants and L-asparaginase

• Total and free protein S levels and

functional assay of protein S is done after

discontinuation of anticoagulants.

• Treatment with heparin; warfarin in case

of recurrent thrombosis

Activated protein C resistance

• Commonest inherited thrombotic

disorder

• Autosomal dominant, usually

associated with a single point

mutation in factor V gene (Arg to Gln

at position 506)

• Prone for venous thrombosis

• Assay is done after discontinuation of

the anticoagulants

Antiphospholipid

antibody syndrome

• Antiphospholipid antibodies may be IgG,

IgA or IgM

• Different antibodies are

–

–

–

–

anticardiolipin

antiphosphatidyl ethanolamine

antiphospahtidyl serine

antiphosphatidyl choline.

• Characterized by

– Recurrent arterial or venous thrombosis

– Recurrent fetal loss

– Livedo reticualris

Livedo reticularis

• β2 glycoprotein in plasma is needed to

bind to cardiolipin.

• Occurs as

– Secondary to SLE, other autoimmune diseases,

Sneddon’s syndrome, acute and chronic

infections, neoplasias, IBD, drugs, severe pre

eclampsia, liver transplantaion

– Primary APLA syndrome

• Treatment

– High dose warfarin to keep INR above 3 with

or without aspirin

– In pregnancy, low dose aspirin and prednisone

is given

Infarcts of

undetermined cause

(Cryptogenic stroke)

• In many cases the cause of the

ischemic event is not identified even

after after an extensive work up

• Occurs in 20 to 50% of people with

young stroke

• Recurrence risk in such cases is less

INTRACEREBRAL

HEMORRHAGE

• Vascular malformations

• Intracranial tumours

• Bleeding disorders, anticoagulant and

fibrinolytic treatment

• Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

• Granulomatous angitis of the central

nervous system

• Hemorrhagic infarction

• Trauma

Vascular malformations

• The vascular malformation may be

– Saccular or mycotic aneurysms

– Arteriovenous malformations

– Cavernous angiomas

• Intracerebral hemorrhages caused by

small lesions are characterized by

–

–

–

–

–

Located in the subcortical white matter

Hematoma is smaller

Symptoms develop slowly

Usually subarachnoid hemorrhage seen

Younger patients with female preponderance

• MRI or histological examination needed for

diagnosis

• Aneurysms

– On the basis of morphology, aneurysms

are classified as saccular, fusiform or

dissecting.

– Saccular aneurysms are more often

acquired than congenital

– They tend to occur at the branching

points in the circle of Willis and proximal

cerebral arteries (40% in anterior

communicating artery).

– Usually presents as SAH; less commonly

as ICH, space occupying lesion

producing compression, seizures,

embolism from thrombus,

hydorocephalus

• Associations of intracranial saccular

aneurysms

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Polycystic kidney disease

Fibromuscular dysplasia

Cervical artery dissection

Coarctation of the aorta

Intracranial vascular malformations

Marfan’s syndrome

Ehler-Danlos syndrome

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

Moyamoya syndrome

Klinefelter’s syndrome

Progeria

Types of aneurysms

• Arteriovenous malformations

– Abnormal fistulous connections between

one or more hypertrophied feeding

arteries and dilated draining veins

– Diagnosis suspected in Ct scan. Nonenhanced scan shows calcification and

non-specific hypo- or hyperdensity.

– Contrast CT scan shows dilated veins of

large malformations.

– MRI or angiogram may be needed to

confirm diagnosis.

• Cavernous hemangioma

– Detected using MRI

– Shows a central nidus of irregular bright

signal intensity mixed with mottled

hypointensity, surrounded by a

peripheral hypointense ring

– Hemosiderin deposits in periphery due

to prior bleeding

– Usually single lesions

– Predominantly supratentorial, presents

as seizures

Intracranial tumours

• Bleeding into tumour occurs with

– Glioblastoma multiforme

– Metastasis from melanoma, bronchogenic

carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma,

choriocarcinoma

• Relatively rare complication

• If suspected, search for primary or

secondary brain tumour and systemic

focus

• Cerebral angiography and craniotomy for

biopsy of hematoma wall may be needed

• Extremely poor prognosis

• Suspicion of an underlying tumour should

arise when

–

–

–

–

Presence of papilloedema at presentation

Rare location, e.g., corpus callosum

Presence of ICH in multiple sites

Ring of high density hemorrhage surrounding a

low density centre in non-enhanced CT scan

– Disproportionate surrounding edema and mass

effect

– Enhancing nodules adjacent to h’ages in

contrast CT scan

– MRI showing heterogeneous signal lesions

within a mass lesion , surrounded by

hemosiderin hypointense ring and bright signal

edema at periphery in T2

Bleeding disorders

• Hemophilia A

• Immune mediated thrombocytopenia

– Platelet count < 10,000/μl

• Acute leukemia

– Acute lymphocytic leukemia

– Acute promyelocytic leukemia – due to

DIC

Anticoagulants

• Risk factors for IC bleeding

– Advanced age

– Hypertension

– Preceding cerebral infarction

– Head trauma

– Excessive prolongation of prothrombin

time

– Severe leukoareosis in CT scan

• Slowly progressive course, larger

collections causing high mortality

Fibrinolytic agents

• Thrombolysis with streptokinase or

t-PA for MI and use of intravenous

t-PA or intraarterial prourokinase for

ischemic stroke associated with ICH

in 0.6% and 6.4% respectively.

• Complication more in those with preexisting vasculopathies

• Risk factors for ICH in thrombolysis

of cerebral infarct

– Severe neurological deficit at

presentation

– Documentation of hypodensity or mass

effect on CT before treatment

– Hyperglycemia pretreatment

– Microhemorrhages detected in gradientecho MRI sequences after thrombolysis

• H’ages occur at the site of preceding

cerebral infarct

• Dismal prognosis

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

• Occurs in the elderly

• Selective deposition of amyloid in cerebral

vessels, primarily small and medium-sized

arteries of cortex and leptomeninges

• Recurrent and multiple lobar hemorrhages

• Associated with Alzheimer’s disease

• Histology – congo red positive,

birefringent amyloid material in the media

an dadventitia of arteries

Sympathomimetic agents

• Cocaine, amphetamine and

phenylpropanolamine implicated

• Risk increased with heavy alcohol

intake

• Mechanism – Hypertension and drug

induced vasculitis

Conditions producing both

ischemic and h’agic strokes

• Hypertension

• Moyamoya disease

• Vasculitis

• Cocaine and other sypathomimetic

drugs

Causes of arterial and

venous thrombosis

• Homocysteinemia

• APLA syndrome

• Protein S deficiency

APPROACH TO

A YOUNG PATEINT

WITH STROKE

• History

– Presentation similar (R/o multiple

sclerosis and malignancy)

– Presence of risk factors

– H/o drug intake, hematologic disordrs,

cardiac disease, vasculitis, infections,

radiation

Physical examination

• Ocular findings

– Corneal arcus (hypercholesterolemia)

– Corneal opacity (Fabry’s disease)

– Lisch nodules, optic atrophy

(Neurofibromatosis)

– Lens subluxation (Marfan’s, homocystinuria)

– Retinal perivasculitis (sickle cell disease,

syphilis, connective tissue disease, IBD)

– Retinal occlusions (emboli)

– Retinal angioma (cavernous malformation)

– Hamartoma (tuberous sclerosis)

– Roth spots (infective endocarditis)

• Dermatologic examination

– Splinter hemorrhages, Osler’s nodes,

Janeway lesions (endocarditis)

– Xanthoma (hyperlipidemia)

– Café-au-lait spots, neurofibromas

(neurfibromatosis)

– Purpura (coagulopathy)

– Capillary angiomata (cavernous

malformation)

• Cardiovascular examination

Approach to investigations

CT scan brain /MRI brain

Urine routine

Hb, TC, DC, ESR, Platelet count

PCV, Peripheral smear

Blood sugar, renal function,

electrolytes

• Premature atherosclerosis

– Blood sugar

– Lipid profile

– Urine homocysteine

– Lipoprotein (a)

– Serum fibrinogen level

– Cystathionine synthetase level in

cultures of fibroblasts or liver biopsy

• Coagulation profile

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

PCV, platelet count

Red cell mass

PT, INR, aPTT

Antiphospholipid antibody

Protein C, protein S assay

Activated protein C resistance

Sickle cell preparation, Hemoglobin

electrophoresis

Serum viscosity, fibrinogen levels

Ham test, sucrose lysis test

Bone marrow study

Prothrombin mutation G20210A testing

• Cardiac study

– ECG

– Chest X ray

– Transthoracic or transesophageal

echocardiography

– 24 hour Holter monitoring

– Coronary angiography

– Gum or rectal biopsy for amyloid

(cardiomyopathy)

• Vasculitis

– ESR

– Autoantibody profile

– VDRL, HIV, HBsAg

– Mantoux test, sputum AFB

– CSF study

– Leptomeningeal biopsy

• Miscellaneous

– Toxiclogical studies

– Serum lactate

• Further imaging studies

– MRI brain

– MRI with diffusion weighted imaging and

perfusion imaging

– Extracranial (carotid-vertebral) doppler

ultrasound

– MR angiogram

– Cerebral arteriography

Treatment

• The management in the acute stage

of stroke is similar to that of usual

atherosclerotic CVD

• Further management depends upon

the underlying cause

• Prognosis is usually much better than

strokes in older individuals

• Chance of recurrence high if the

primary cause is not corrected

Summary

• Stroke in young individuals is a

common phenomenon

• The differential diagnosis of the

etiology is wider than for strokes in

older individuals

• Patients should be judiciously

investigated depending on other

clinical features

• Prognosis is usually better

Bibliography

• Neurology in clinical practice – Bradley, 4th

edition

• Principles of neurology – Adams, 6th

edition

• Merrit’s textbook of neurology – 6th edition

• Brain’s diseases of nervous system – 10th

edition

• Harrison’s principles of internal medicine –

16th edition

• Stroke – Journal of American Heart

Association