Case Study 20

advertisement

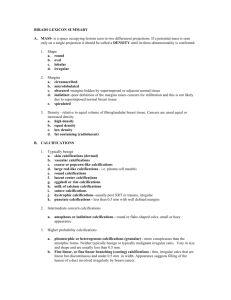

Case Study 20 Craig Horbinski, M.D., Ph.D. Question 1 The patient was a full-term, 4-week-old baby who presented with failure to thrive, lethargy, hypotonia, poor feeding, rapidly developing apnea and bradycardia, and hypothermia. CT and MRI scans were performed. What do you see? What is the likely cause? CT CT T1 T1 Answer Extensive diffuse cerebral encephalomalacia with calcifications (best seen on CT) and relative sparing of some deep grey matter structures and posterior fossa. Intrauterine TORCH infection is the most likely cause, but an intrauterine stroke is also a possibility. Question 2 Additional clinical history reveals that the patient was born to a G4 P2 mother via cesarean section without complications. The pregnancy was uncomplicated with no infections and normal fetal movements and only gestational diabetes (controlled by diet.) Mother was GBS negative, and there was no history of HSV 1 or 2, and prenatal labs were negative. The mother reports that the baby seemed normal for the first few days of life but then at four days of age she noted that he was having repetitive twitching and jerking of the upper and lower extremities which did not stop with stimulation. He also was very lethargic and had to be awakened for feeds, and did not fix or follow well. Blood, urine, and CSF cultures were negative. Toxoplasmosis, CMV, and rubella titers were negative. An ophthalmologic exam revealed possible retinitis. He developed progressive apnea and bradycardia. The severity of the baby's brain injury and the grim prognosis were discussed with the family, whereupon they chose to withdraw further care. The patient died one day later. You are asked to perform the autopsy on the brain. What do you see? Answer Severe symmetric encephalomalacia of the entire cerebrum, sparing only the posterior portion of the occipital lobe, the diencephalon (thalamus), cerebellum, and brainstem. Coronal sections of the left cerebral hemisphere reveal extreme hydrocephalus ex vacuo, with complete obliteration of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes as well as obliteration of the basal ganglia and hippocampus. The thalamus and hypothalamus are relatively spared. Question 3 The eyes are sent to you separately for evaluation. Externally, they were both unremarkable, so you sectioned them to examine the interior. What do you see? (FYI, both eyes looked like this.) Answer The retina has several well demarcated patches of tan to dark brown mottling. Question 4 You get the eye slides before you get the brain slides. What do you see? What should you do next? Click here to view slides. Answer There are discrete areas of retinal necrosis with dystrophic calcification, some associated disruption of the retinal pigment epithelium, and chronic chorioretinitis. The correct term to use for the retinal lesions is necrotizing chorioretinitis with dystrophic calcification. These are the sort of lesions seen in TORCH infections, so immunostains for TORCH infectious agents, in particular toxoplasmosis, CMV, and HSV1/2, are appropriate. (Because it is so rare due to vaccinations, rubella immunostain is not available in the immunohistochemistry lab.) Question 5 While you’re waiting for the immunostains on the retinal lesions, the brain slides arrive. Sections of the frontal lobe and thalamus are shown for your review. What do you see? What’s the best term to use for this in the final diagnosis? Click here to view slides. Answer Sections of the cerebral hemisphere show no recognizable cortical or subcortical structures, only a mass of blood vessels, macrophages, and calcifications. The thalamus has extensive neuronal loss along with scattered macrophages and calcifications. This is best diagnosed as severe cystic encephalomalacia with extensive calcifications. Question 6 The immunostains on the retinal lesions have arrived. Assuming the other immunostains are negative (they were), what do you think of these stains? What do they mean? Click the following links to view slides: HSV1/2, HSV2, HSV1 Answer The immunostains show positive cells for HSV1/2 and HSV2. HSV1 is negative. This is proof of an HSV2 infection. In the eye, take care to 1) order the stains with red chromogen so they’ll stand out from the disrupted brown retinal pigment epithelium; 2) only consider nuclear staining as positive for herpesvirus, as some of the macrophages have granular cytoplasmic positivity that may be due to incompletely quenched endogenous peroxidase activity. Question 7 Additional immunostains on the brain were attempted, but all were negative. Moreover, repeat HSV PCR on 2 separate samples of the patient’s CSF at 2 separate laboratories was negative. Does this change your overall diagnosis in this case? Answer No. The combination of severe encephalomalacia and bilateral retinitis is a classic presentation of an intrauterine TORCH infection. It is not uncommon for the virus to be difficult to detect immunohistochemically in the brain, as the process may have “burned out” by the time you see the specimen. The negative PCR findings may also reflect this “burned out” status, or may be due to a technical problem with the assays. Question 8 What are the TORCH infections? Why are they lumped together in an acronym? Is there anything weird about the cause in this case being a herpesvirus? Answer TORCH infections are the collection of nonbacterial agents known to cause perinatal central nervous system disease. These include Toxoplasmosis, Other (e.g. syphilis, varicella-zoster, parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. These agents are grouped together because most produce similar clinical and pathologic findings, including chorioretinitis, cerebral atrophy with periventricular calcifications, and severe neurologic sequelae. These are usually acquired via the transplacental route in either the first or second trimester. One notable exception is herpesviruses, which are mainly acquired via passage through the birth canal. Identifying the causative agent requires additional immunohistochemical and molecular diagnostic studies aimed at all the potential agents, not just a few. This case of TORCH is unusual because the causative agent was herpesvirus type 2. As stated above, the majority of herpes simplex virus TORCH infections are acquired during passage through an infected birth canal. This baby was born via caesarean section, so the infection must have been transmitted via the less common transplacental route. Also, the absence of an HSV history or positive prenatal lab result clearly does not exclude these agents when evaluating a case pathologically.