Roger Laidlaw presentation

advertisement

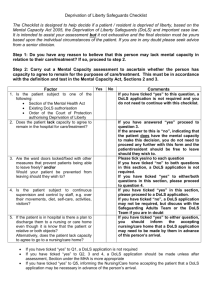

Why the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards should matter Roger Laidlaw DoLS Co-ordinator for RCT, Merthyr Tydfil and Cwm Taf Health Board Speaking very much, in a personal capacity! Why the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards should matter • • • • DoLS – What is it? Where did it come from? Where is it going? What does it mean for me as an advocate? The Mental Capacity Act 2005 Key concepts: • Mental capacity – an ability to take decisions effectively, using information and foreseeing consequences If an individual demonstrably lacks mental capacity, others may decide on the basis of: • best interest – a focus on the circumstances and wishes of the individual • by considering the least restrictive alternative Seeking and considering the person’s views is a fundamental principle of the Mental Capacity Act: ‘No decision about me, without me’ ‘DoLS’ • Part of the Mental Capacity Act • Safeguards cover people in hospitals and care homes registered under the Care Standards Act 2000 • Became statutory obligation from 1st April 2009 No statutory definition of a DoL! However, indications may be: • • • • Requirement to reside in an institution Interference with autonomy Restricting access by family / to outside world Opposed by the person themselves or supporters • Conceived as being more intrusive than a ‘restriction’ of liberty • Definitions being ‘refined’ by case law DoLS Procedure in a Nutshell: • A system of referral and assessment intended to inquire if a DoL is taking place, if these arrangements are beneficial for the resident or patient, and if restrictions can be reduced in intensity • Makes Local Authorities and Health Boards the competent ‘Supervisory Bodies’ to Authorise any legitimately required DoL thus providing legal safeguards for the staff giving care or treatment • Arrangements for scrutiny and review of Authorised DoLS DoLS Procedures are not … • a new set of powers intended to facilitate oppressive practice and make short-cuts in the management of clients with challenging needs easier for hospital and care home ‘Managing Authorities’ • intended to exclude supporters from decision making about vulnerable people • Court of Protection case law makes it clear that attempting to manipulate procedures to these ends is simply standing the intention of the Safeguards on its head. The intention of DoLS procedures … • Is to co-ordinate 6 assessments applying the tests of the MCA with transparency and rigour to the specific circumstance of a possible Deprivation of Liberty and then: - Note the presence / absence of a DoL - Authorise or seek end it The six assessments • Is the person over 18? • Do they have a mental disorder? (the diagnostic test) • Do they lack mental capacity to make a decision about care? (the functional test) • Is the received / proposed support in their ‘best interest’? • Should the Mental Health Act be used instead? (primacy of the MHA) • Is there a conflict with another decision making authority given under the MCA? • If all tests are ‘positive’, care amounting to a deprivation of liberty can (and must) be ‘Authorised’ by the relevant Supervisory Body: - Authorisation can be given for up to a year (but mostly for shorter periods) - Binding conditions can be set on the care home or hospital ‘Managing Authority’ • The scheme is supposed to focus awareness on alternative arrangements and the possibility of reducing restrictions, mitigating or working to end the Deprivation of Liberty, for example: - changes to care plan - an ultimate return home? • Regarding DoLS simply as a way of locking someone up or as empowering institutions against the individual or their supporters is standing Safeguards on their head Steven Neary – Does DoLS work? Victory for father after autistic son's 12-month ordeal in the clutches of social workers By Daily Mail Reporter 10th June 2011 Where did DoLS come from? • Long term trends for inclusion and the promotion of rights for members of marginalized groups, • Shift from paternalism to law • Important legal cases establishing key concepts / highlighting gaps in law in the European Court and UK Courts - ‘judicial activism’? Background • An international trend to move away from the ‘licensed paternalism’ of reliance on judgments about welfare being part of a purely professional discourse towards decision making having to be transparently justified against externally established and formalised legal criteria • (For nerds, consider the ‘Bolam test’) Background - national legislation and international agreements about standards for judgment • UK Human Rights Act 1998 • Adults with Mental Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 • Hague International Convention on the protection of adults 2000 • Mental Capacity Act 2005 • United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities 2006 • A statutory Code of Practice for social care in England or Wales? Two key pieces of case law that highlighted gaps in the law for determining the welfare of incapacitated people and led to the development of the DoLS regime • The “Bournewood” case, HL vs UK – a ECtHR case - UK Govt found to be in breach of Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights. • DE and JE v Surrey County Council Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) • 5.1. Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be deprived of his liberty save … in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law • 5.4. Everyone who is deprived of his liberty … shall be entitled to take proceedings by which the lawfulness of his detention shall be decided speedily by a court and his release ordered if the detention is not lawful. The Bournewood Gap • The absence of an article 5 ECHR compliant legal framework The Gap also existed because: • MHA did not apply to care homes • Excludes most people with a learning disability • Not used for people who do not or cannot object to admission Problems with DoLS Bad drafting and poor planning of scheme: • Includes an obvious and immediate conflict of interest as LAs and LHBs are both poachers and gamekeepers, as purchasers / commissioners or providers of care that may amount to DoL and the legal authorities appointed to Supervise and Authorise DoL Problems with DoLS • Limited commitment of resources by some authorities • No coverage of supported living arrangements based on tenancies (the jurisdiction of the Court of Protection applies) Problems with DoLS • A ragged interface with the Mental Health Act: Justice Peter Jackson, said it’s ‘regrettable’ this is difficult to understand even by lawyers and professionals • Poor and patchy implementation: widely varying rates of applications and authorisations Problems with DoLS • Recent case law has arguably narrowed the scope of the scheme by narrowing the scope of what might be a DoL by focussing on ‘context’ and comparison with care arrangements in similar cases and considering ‘relative normality’ when considering limits to autonomy • This may not in itself be a problem but many respected commentators think this might be a retreat of HRA criteria from health and social care • Since MCA / DoLS was implemented in its present form because of judicial concern and some of the same individuals who ‘made’ the case law seem now in more senior legal roles to be restricting the scope of judicial oversight this can be a little puzzling! Low rate of reviews, a key factor • Certain high profile cases notwithstanding, and though intended to give a route for valid challenges, in general, review activity under the Safeguards has been extremely low • Historically, the under the MHA, a high rate of challenge to detention based on effective scrutiny under an authoritative legal regime is probably the key factor is making professionals and organisations respect the rights of people with mental health problems Second class liberty? High thresholds for inclusion in the scheme, confusion about key issues, limited and patchy implementation, ineffective review regime: • Does DoLS represent ‘Second class liberty’? • A lack of legitimacy and effectiveness has led some more hostile commentators to conclude ‘DoLS is Dead’ What next? • Further developments in case law • The ‘West Cheshire case’ is in the Supreme Court October 2012 and may establish clarity about what constitutes DoL / establish legitimacy of process / may end or cool an overheated discussion Compliance with international law requirements • MCA / DoLS out of step with approach in other legal jurisdictions in some respects: • An approach of ‘supported decision making’ instead of an allegedly ‘paternalist’ best interest approach • In European law detection of ‘DoL’ focussed on objective measurement of autonomy and restriction, not ‘comparitors’ Undeniable that ‘Human Rights’ have become a political football. Will this have an impact on social care and medicine which are increasingly reliant on ECHR standards, e.g. art. 14 outlawing discrimination? • Removal of HRA from E and W law? • Replacement with a ‘Bill of Rights’? • A big change or in fact little impact? However, • DoLS is still law • There are no plans to remove the scheme from the law books • Legal reform for MCA and MHA has previously been measured in decades! • If DoLS ‘falls’ or even if HRA should be removed from British law, the case law precedents will remain in England and Wales law • DoLS would undoubtedly have to be replaced by an alternative legal regime (and probably something odder and uglier!) • The long term trend towards the formal recognition and support of the rights of service users, patients and vulnerable people as citizens through a legal framework is based on fairly fundamental changes in society and social attitudes and will probably continue … and meanwhile: DoLS isn’t dead – it just smells funny What does it mean for me? Advocate roles in DoLS • DoLS may be a mess but the only occupational group coming out of the case law reports with uniformly positive comments seem to be advocates! • Being consulted in assessments about users’ views • Ensuring that processes are followed • Acting as paid representative, depending on local commissioning arrangements • s. 39 IMCA giving support to representatives and making the protections work • Third Party referrals in DoLS: initiating assessments Third party DoLS applications • Anyone at all can notify the Supervisory Body of a potential DoL: sometimes just asking about DoL is sufficient for an authority reconsider a care plan • Few explicit 3rd party referrals are made, and most are made by professionals or advocacy staff • There is a suggested form but completing this is not a requirement • Hospital and care home staff, care managers, duty officers and complaints staff need to be alert to this issue and assist people contacting DoLS Coordinator DoLS and Safeguarding • DoLS giving legal ‘teeth’ in Safeguarding cases, can authorise: • A placement or further hospital stay as part of a protection plan • Setting limits on contact and association with potential abusers • A proposed social care Code of Practice may enhance statutory powers for organisations involved in safeguarding and existing DoLS powers may complement this Summary – why should DoLS matter? • MCA and DoLS give a common terminology and set of tests for discussion about service user welfare and self determination Summary – why should DoLS matter? • A potentially powerful set of safeguards for challenging the arbitrary or careless use of legal and professional power which are being under-used. Summary – why should DoLS matter? • If you don’t understand the processes clearly, and can be bamboozled by professionals, your assistance to service users will be less effective. • If you don’t understand DoLS seek training!