Emergency Lecture Series Approach to Common

advertisement

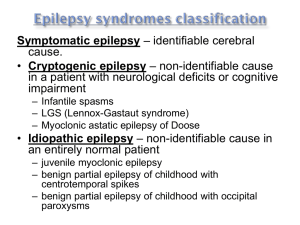

Emergency Lecture Series Approach to Common Pediatric Neurology Consults A Case-Based Approach Ruba Benini Pediatric Neurology (PGY2) McGill University 4/August/2010 Outline Febrile seizures Afebrile Seizures (Childhood epilepsy syndromes) Headaches Ataxia Hypotonia Case 1 : 14mo bb girl, history of irritability and lethargy for 3days. Brought to ER by parents because of sudden episode of body stiffening followed by limpness and fine shaking of all extremities for 1min. In ER, BP=75/50; HR= 150/min; RR=40/min; T=38.6C rectal; O2 sat=98% RA. Case 2: 14mo bb girl, history of irritability and lethargy for 3days. Brought to ER by parents because of sudden episode of body stiffening followed by limpness and fine shaking of right arm and leg lasting 20min. In ER, BP=75/50; HR= 150/min; RR=40/min; T=38.6C rectal; O2 sat=98% RA. Case 3: 14mo bb girl, ex-34weeker, known seizure disorder, on Frisium, history of irritability and lethargy for 3days. Brought to ER by parents because of sudden episode of body stiffening followed by limpness and fine shaking of all extremities for 1min. In ER, BP=75/50; HR= 150/min; RR=40/min; T=38.6C rectal; O2 sat=98% RA. Approach to Febrile Seizures Febrile seizures are defined as seizures that occur in association with fever, in the absence of CNS infection (meningitis, encephalitis) and in patients with no history of previous afebrile seizures Occur in 3-4% of children between 3months – 6 years (peak age 18-24months) High recurrence (30-40%) 10% of children experience 3 febrile seizures Factors that increase risk of occurrence include: Young age at time of first febrile seizure (<18months) Family history of in first degree relative Low degree of fever while in the emergency department Brief duration between onset of fever and the first seizure Etiology – genetic predisposition 40% concordance rate for monozygotic twins versus 7% for dizygotic twins 8% if sibling with febrile seizures, 22% if sibling + parent Mode of inheritance: polygenic vs autosomal dominant with variable penetrance Approach to Febrile Seizures Classification Simple (typical) Complex (atypical) •Generalized •Focal •<15min in duration •>15min in duration (status epilepticus) •No recurrence in a 24hr period •Normal neurological status before seizure •Multiple episodes in a 24hr period •Abnormal preexisting neurological status before seizure Risk of developing epilepsy in general population: ~1% Not increased with simple febrile seizures except might be mildly increased if multiple episodes, FHx of epilepsy, and age <12months at first seizure Increased to 2.4% with atypical febrile seizures Risk of epilepsy increased with the presence of each atypical feature: • • • • One atypical feature – 3% Two atypical features – 6% Three atypical features – 9% Four atypical features – 12-15% Approach to Febrile Seizures Treatment of febrile seizures and prevention of recurrences does not alter risk of later possible epilepsy - routine use of AEDs not recommended. Parents can be advised to use anti-pyretics for comfort care, but there is no evidence that it prevents recurrence of febrile seizures Intermittent benzodiazepine can be used when recurrence is expected; excessive parental anxiety Nitrazepam (Mogadon) < 2years 1.25mg TID >2years 2.5mg TID What investigations are necessary: Simple febrile seizures: nothing Complex febrile seizures: EEG ± neuroimaging What do parents want to know: Is this harmful Will it happen again Can I prevent it? Will my child develop epilepsy Will it go away? (Minimum 3days or until fever subsides) Case 4 : 8 year old boy, developmentally normal, with previous history of febrile seizures (5 febrile seizures since age of 1), presenting with generalized tonic-clonic seizure lasting 1 minute in the context of a febrile illness. Case 5: 3year old boy, with history of 5 febrile seizures in the past. First febrile seizure was atypical, at age of 7months. Subsequent seizures have different semiology (atonic,myoclonic). Was meeting developmental milestones until ~1.5years ago when he began to deteriorate with regression in development. Myoclonic jerks at age 18months. Approach to Febrile Seizures Consider other entities when febrile seizures : Occur very frequently; or Past the conventional age of 6 years (sometimes 7 or 8 years is used as upper limit); or In the context of deteriorating development Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy of Infancy (Dravet Syndrome) •Intractable epilepsy •Begins in first year of life usually with prolonged hemiclonic febrile seizures •Over time seizures evolve into febrile/afebrile generalized seizure types (myoclonic, atypical absence and partial complex) which rapidly become refractory to AEDs Generalized Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus (GEFS+) •Febrile seizures begin in usual age range but persist beyond 6 years of age •Different seizure phenotypes may develop: myoclonic, atonic, astatic, or partial complex seizure •Mutations in SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN1B, GABRG2 •Myoclonic jerks between 12-36months •Prior to onset of seizures child is developmentally normal ataxia, psychomotor regression, mental retardation •EEG initially normal generalized spike wave abnormalities •70% have mutation in SCN1A Avoid AEDs that block Na channels: lamotrigine, CBZ, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin Rx: clobazam, VPA Stafstrom 2009 Approach to Febrile Seizures Outline Febrile seizures Afebrile Seizures (Childhood epilepsy syndromes) Headaches Ataxia Hypotonia Approach to Afebrile Seizures Seizure Provoked Unprovoked •Electrolyte abnormalities •Infection (meningitis) •Trauma •Toxic ingestion Does it fit any of the Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes? •Vasculitis •Semiology of seizures •Inborn error of metabolism •Age of onset •CNS tumour •EEG features •Clinical features/progression •History •Exam •Investigations: lytes (Glc, Ca, P, Mg); CBC; LP; tox screen, etc) •Neuroimaging •Response to Rx •Prognosis Approach to Afebrile Seizures Approach to Afebrile Seizures History Serologies/TORCH Preeclampsia/GDM/Infections Substance abuse/meds •Antenatal History •Birth history Antenatal U/S Fetal distress Apgars, Cord pH Need for postnatal resuscitation •Developmental history Normal vs delayed vs regressed •Family history •PMHx (?CNS infections) •Head trauma •Seizure description (aura, trigger, eyewitness description) Consanguinity, hx of febrile seizures, epilepsy, developmental delay, recurrent miscarriages, IEM Approach to Afebrile Seizures Physical Exam •Dysmorphism •Stigmata of Neurocutaneous disorders •Neurological exam including •HC • developmental •?Liver, heart involvement (IEM) Approach to Afebrile Seizures Physical Exam •Dysmorphism •Stigmata of Neurocutaneous disorders •Neurological exam including •HC • developmental •?Liver, heart involvement (IEM) Approach to Afebrile Seizures Physical Exam •Dysmorphism •Stigmata of Neurocutaneous disorders Shagreen patch (Tuber Sclerosis) Hypopigmented macule (Tuberous sclerosis) •Neurological exam including •HC • developmental •?Liver, heart involvement (IEM) Café -au -lait macule (Neurofibromatosis) Port Wine Stain (Sturge=Weber) Developmental Approach to Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes http://www.ilae-epilepsy.org/Visitors/Centre/ctf/CTFsyndromes.cfm Neonate (<28days) Case 6 : Called from NICU to rule out seizures in a 5day old baby boy, ex-34 weeker. Unremarkable antenatal history except baby was born at 34weeks because of PROM. GBS status unknown. No maternal fever. Mom received antibiotics 5hrs prior to delivery which was by SVD. BB born with Apgars 7,9. Cord pH 7.24. On DOL 1 baby started having apneic episodes lasting 10secs, associated with bradycardia and desaturation. Might have had one episode of generalized tonic-clonic movements of extremities lasting 3secs. Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Neonatal Period (<28 days) Seizures in newborns are often difficult to distinguish from normal activity Most commonly occur within the first week of life 2/3 of neonatal seizures are due to Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) Other causes: infection, electrolyte abnormalities, inborn errors of metabolism, structural The clinical and electroencephalographic features of neonatal seizures differ considerably from those in older children and adults. Some seizures can be quite subtle making diagnosis difficult Important to note that in neonates 50%-80% of prolonged epileptiform discharges on EEG are not associated with visible clinical changes This electroclinical dissociation is due to the Incomplete myelination of white matter tracts and immaturity of regional brain interconnectivity Leads to only modest behavioural manifestations of seizures and explains why unlikely to get tonic-clonic seizures in newborns Feinichel Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes •Sudden jerking movements during sleep only •Can be stopped with gentle restraint •Normal EEG •No Rx •Excessive response to stimulation •Low frequency, high amplitude shaking of limbs and jaw in response to touch, noise or motion •Low threshold for Moro reflex Feinichel Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes •Almost never a seizure manifestation unless associated with eye deviation, tonic stiffening •Prolonged apnea without bradycardia & with tachycardia is a seizure until proven otherwise •Often associated with HIE ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Approach to Neonatal Seizures Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy Epilepsy syndromes Infection Electrolyte abnormalities Structural Inborn errors of metabolism Benign Epileptic encephalopathies Stroke Feinichel Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Neonatal Period (<28 days) Benign Familial Neonatal Seizures Benign Familial Neonatal-Infantile Seizures •FHx of seizures in first weeks of life with no epilepsy or neurologic abnormalities •Onset between 6days of life to 3months •Autosomal dominant, mutations in voltage-gated K channels •Seizures are partial in onset then become generalized •Brief multifocal clonic seizures during the first week ±apnea •Seizures stop spontaneously by age 12months •Seizures stop spontaneously within 6weeks •Healthy newborn, normal interictal EEG, clinical events are associated with flattening of the EEG •Rx: Phenobarbital, then taper off when seizure free for 4weeks Feinichel Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Neonatal Period (<28 days) Epileptic encephalopathies : seizures lead to severe cognitive and behavioral impairment Early Myoclonic Encephalopathy •Erratic/fragmentary myoclonus that typically is not associated with an EEG correlate •EEG shows burst suppression pattern •Usually normal MRI findings Ohtahara Syndrome (Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy) •Frequent extensor tonic spasms •EEG shows burst suppression pattern •Usually abnormal MRI findings (lissencephaly, focal cortical dysplasia,etc) •Medically intractable seizures •Sometimes associated with certain inborn errors of metabolism ex. Nonketotic hyperglcemia, Menkes disease, proprionic acidemia, etc Chapman and Rho Infant (<2yrs) Case 7 : 8mo bb girl, developmentally normal, presents to ER with 3 weeks history intermittent sudden jerky movements of the head and upper extremities, lasting 1-2secs, worsening over the course of the past 3 weeks. Multiple episodes a day, sometimes in clusters. Resumes activity right after jerk with no apparent alteration. No other unusual movements. Unremarkable perinatal history. No FHx of epilepsy or other seizure disorders. Exam normal except for myoclonic jerks noted. Video-EEG normal, with no associated changes during myoclonic episodes. Case 8 : 8mo bb girl, developmentally delayed, presents to ER with episodes of stiffening of upper extremities and abduction of arms. Multiple episodes a day, sometimes in clusters lasting 5-10min since 6months of age. Exam abnormal – unable to sit without support, truncal and lower extremity weakness. Flexor spasms of upper extremities noted. One hypopigmented macule on back. EEG shows hypsarrhythmia with electrodecrimental changes associated with spasms. MRI shows subcortical tubers. Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Infancy (<2yrs) Benign myoclonus of infancy Benign myoclonic epilepsy West Syndrome (infantile spasms) Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy of Infancy (Dravet syndrome) ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Infancy (<2yrs) Benign myoclonus of infancy Benign myoclonic epilepsy Age of onset Seizures EEG pattern Clinical features Rx 4 to 7months Similar to infantile spasms Occur in clusters usually around mealtime Worsen over course of next weeks/months then stop spontaneously Normal Normal exam None required Myoclonic jerks Spike & wave (3cps) 4months2yrs (head noddingsevere enough to throw child onto floor) Normal development Resolves by age 2yrs Polyspike & wave (3cps) Normal exam VPA Levetiracetam Normal development Resolves by age 2yrs Infantile spasms 4 to 7months Brief symmetric contractions of neck, trunk, extremities (flexor, extensor, mixed) Hysarrhythmia Slow spike & wave Burstsuppression Abnormal exam ACTH Vigabatrin Abnormal development *Tuberous sclerosis ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Infancy (<2yrs) West Syndrome (infantile spasms) •Triad of infantile spasms, hypsarrythmia on EEG, and developmental arrest/regression •Peak age of onset 3-7months •Most common epileptic encephalopathy •Etiologies: •Cerebral dysgenesis •Tuberous sclerosis •Preexisting injury 2o ischemia, infection or trauma •Down syndrome •IEM http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fEgAjCv7VQo&NR=1 ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Child (2yrs - adolescence) Case 9 : Healthy 7 year old boy, brought to ER because parents noticed unusual event after patient went to bed. Heard gurgling noises from his room, found him sitting in bed with right lower face jerking, excessive drooling and unable to speak. Lasted 2min and was completely back to baseline. Developmentally normal. Exam normal. EEG shows … Case 10 : Healthy 6year old girl, brought to ER because parents noticed unusual event. Patient hurt herself whilst playing outside. Came indoors to mom, crying +++ then suddenly she stopped crying, eyes staring ahead, some blinking movements. Lasted 5secs then she snapped out of it and continued crying. Developmentally normal except parents report she is often “dans la lune”. Also, teachers complain that her grades have dropped during this academic year and that she continuously “stares off into space”. Exam completely normal. Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood BECTS Childhood Absence Epilepsy Lennox-Gastaut Landau-Kleffner ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal spikes (BECTS/Rolandic epilepsy) •Most common form of idiopathic epilepsy in childhood •Peak age of onset: 5-10years (range 3yrs-13yrs) •Developmentally & intellectually normal •Strong genetic predisposition •Seizures: •brief (1-2min) •infrequent •10% of children will only have one seizure Majority (70%) will seize 2-6x •Majority have nocturnal seizures only •Hemifacial clonic movements, speech arrest, dysarthria and excessive drooling •Preceding paresthesias in mouth, gum, cheeks or lips may occur •May have involvement of ipsilateral limbs or even generalization ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal spikes (BECTS/Rolandic epilepsy) •EEG •Normal background in awake and sleep •Epileptiform discharges: focal, diphasic spike-and-slow-wave discharges over rolandic/centrotemporal regions; unilaterally or independentally bilaterally •Horizontal dipole with maximum spike negativity over central/temporal regions and maximum positivity over frontal region. •Rx: •Often not necessary unless frequent and disruptive to child’s life •Carbamazepine, Clobazam •Spontaneous resolution by adulthood (18yrs) •*Neuroimaging if EEG findings are focal ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Childhood Absence Epilepsy •Idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome •Age of onset: 4yr to 10 yrs (peak 5-7yrs) •Onset before age 3yrs associated with an increased likelihood of neurodevelopmental abnormalities & probably represents another epilepsy syndrome •More frequent in girls •Developmentally and intellectually normal children •Seizures are brief (4-20secs) abrupt onset of impaired consciousness and unresponsiveness •Typically sudden onset and interruption of activity with blank stare •Abrupt end and child continues ongoing activity unaware that a seizure occurred •If other seizure types present (myoclonic, atonic, tonic-clonic) then not CAE! •Frequent (up to 100s/day) •Provoked by hyperventilation in 90% of children ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Childhood Absence Epilepsy •EEG: ictal events show generalized symmetric 3HZ spike-wave discharges •Prognosis – excellent •Complete remission 2-6yrs after onset •Rx: Ethosuximide, VPA •However, •Up to 30% can continue into adulthood, and these have a greater chance (40%) to get generalized tonic-clonic seizures •CAE can precede juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in 11-18% of cases •Must be differentiated from Juvenile Absence Epilepsy (JAE) •Older age of onset : 10yrs to 16yrs •Infrequent absences with longer duration (>20secs) •More likely to experience generalized tonic-clonic seizures •EEG: 3.5Hz to 4Hz generalized spike-wave discharges •Good response to Rx, but usually lifelong http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3iLQi6wt94&feature=related ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Lennox-Gastaut syndrome •Intractable pediatric epilepsy •Onset: 2 to 8yrs (peak 3 to 5years) •Male predominance •2/3 of cases are symptomatic i.e. have pre-existing brain abnormalities •1/3 of cases have history of infantile spasms •1/3 are cryptogenic affecting children who are initially developmentally & neurologically normal •Classic triad: •Multiple generalized seizure types (tonic, atonic, myoclonic, atypical absence) •Interictal EEG: diffuse slow spike-wave discharges •Cognitive dysfunction (which may not be present at onset) •Poor response to AEDs (VPA, lamotrigine, topiramate) •Ketogenic diet: significant reduction in seizures in 50% of patients •Prognosis: poor with mental handicap in 80% of cases ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Electrical Status Epilepticus in slow sleep (ESES): •Comprises of 2 clinically related syndromes: Continous spike-wave in sleep (CSWS) and Landau Kleffner syndrome •Age of onset: 3 to 8 years •Usually history of normal development with regression in preschool years •CSWS: global regression, decreased intellectual level, poor memory, hyperkinesis, motor impairment, psychosis •LKS: acquired auditory agnosia •EEG: •CSWS: frontal and multifocal sharp waves that become continuous during sleep •LKS: centrotemporal sharp waves that increase during sleep (85% or more of sleep) •These entities are believed to represent the severe spectrum of BECTs •If clinical suspicion, need to admit for 24hr telemetry •Rx: oral steroids and high dose diazepam ILAE 2009 Adolescence Case 11 : 15year old girl, previously healthy and developmentally normal, experienced a 2minute generalized tonic-clonic seizure in the morning while on vacation with parents. Admitted to staying up later than usual. Denied alcohol/substance abuse. Mom reports that for the past couple of years, has had episodes when she would drop her dishes. Also reported early morning limb jerks. Otherwise, developmentally normal. Exam normal. Teaching Point 2: Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Adolescent Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME) Progressive myoclonic epilepsies (PME) •Encompass various metabolic and neurodegenerative conditions that present with progressive myoclonus, gen. tonic-clonic and other seizures, with mental deterioration and cerebellar dysfunction. •Onset: infancy to adulthood •Etiologies: MERRF, Lafora body disease, Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME) •Most common form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy •Age of onset: 12 to 18years (peak 15yrs) •Neurological and developmentally normal •Typically first seizures noted are early morning generalized tonic-clonic seizures precipitated by slep deprivation •Often there is a preceding history of: Myoclonic jerks and absence seizures •EEG: 4Hz to 6Hz generalized atypical spike and polyspike-and-wave discharges with normal background •Photosensitivity in 30-90% of cases •Triggers •Sleep deprivation •Alcohol consumption •Menstruation •Prognosis: excellent response to AEDs (VPA) but lifelong Rx necessary •Avoid carbamazepine, phenytoin and gabapentin as these exacerbate myoclonus ILAE 2009 Common Childhood Epilepsy Syndromes Childhood (2yrs – adolescence) Show videos Not all that shakes or stiffens is seizures …. Case 11 : You’re asked to see a 6month old baby girl who was admitted for ALTE (Altered life-threatening event) to “rule out seizure”. Parents describe an episode lasting ~2min when the baby became “blue and limp”, lost consciousness and had trembling of her arms and legs. Episode was preceded by intense crying. No FHx of epilepsy. Developmentally normal. Exam Normal. EEG was done: Normal. Case 12 : 5month old bb boy, developmentally normal, presenting with episodes of arching, lasting a few seconds. Occur several times during the day. Mostly related to feeds. ROS: Negative, except baby is known for frequent regurgitation of feeds. Nonepileptic Paroxysmal events Nonepilepic paroxysmal events in childhood are common and pose a diagnostic challenge Key to diagnosis is a detailed history and careful observation DiMario 2006 Nonepileptic Paroxysmal events DiMario 2006 Nonepileptic Paroxysmal events Nonepileptic Paroxysmal events Breathholding spells •Represent a prolonged expiratory apnea •Inciting event provokes emotional upset/crying in child •Followed by noiseless pause •Change in colour (pale or cyanotic) •Severe spells can have loss of consciousness loss of postural tone opisthotonic posturing with myoclonic jerks •In 15% of children, can have a generalized convulsion anoxic epileptic seizure •BHS can be divided into: •Pallid BHS: pallor with rapid progression to loss of consciousness •Cyanotic BHS: protracted crying prior to LOC •Age of onset 6-12months with worsening in second year of life •Resolution between 3yrs to 8 yrs •BHS can be exacerbated by anemia •Parental counseling to reduce anxiety http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bKVHSe6hVQ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ne9i2a0lqk&feature=related Nonepileptic Paroxysmal events Gastroesophageal reflux disease (Sandifer syndrome) •Can present as ALTE •Neck and head extension with opisthotonic posturing associated with GER (Sandifer syndrome) •Typically associated with feeding and vomitting •Treatment of reflux with anti-reflux medications reduces frequency of episodes Outline Febrile seizures Afebrile Seizures (Childhood epilepsy syndromes) Headaches Ataxia Hypotonia Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Migraine Brain Tumour Infection (meningitis) Primary Secondary Headache Tension headaches SAH Vasculitis Cluster headaches Head injury Headache Sinus disease ↑ICP (pseudotumour cerebri) Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Red Flags: •Worse headache ever/onset with exertion/thunderclap headache •Fever, nuchal rigidity, behavioural changes •Headade worse in morning/straining/change in head position •Associated posterior fossa signs (diplopia, facial weakness, hearing loss, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, dysmmetria •Papilledema •Worsening or changing quality Brain Tumour Infection (meningitis) SAH Secondary Vasculitis Head injury Headache Sinus disease ↑ICP (pseudotumour cerebri) •Protracted vomiting •B symptoms Investigations tailored towards suspected etiology Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population •Migraine with aura •Migraine without aura •Migraine equivalents Migraine •Acute confusional migraine •Basilar migraine Primary Headache •Cyclic vomitting •Hemiplegic migraine Tension headaches Cluster headaches •Opthalmoplegic migraine •Benign paroxysmal vertigo Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Lewis D et al 2004 Approach to Headaches in Pediatric population Abortive Prophylactic/Preventative Agents •NSAIDs (Ibuprofen) •Flunarizine (Ca channel blocker) •Acetominophen •Topiramate •Triptans (nasal sumatriptan) •Amitryptyline Behavioural interventions Avoid triggers VITAMIN B2 •Valproic acid •Beta blockers (pronalolol) •Cyproheptadine Lewis D et al 2004 Outline Febrile seizures Afebrile Seizures (Childhood epilepsy syndromes) Headaches Ataxia Hypotonia Approach to Ataxia Case 13 : 3year old girl, previously healthy, brought to ER by mother because for the past 24 hrs she has been unsteady on her feet and walking like a “drunk”. PMHx is unremarkable except for low grade fever and cold symptoms 2 weeks prior to presentation. O/E: VSS and afebrile. Patient alert and sitting up in bed. Neck supple. Language appropriate. CN exam normal except for nystagmus on lateral gaze. Truncal ataxia. Dysmmetria (upper and lower extremities). Wide-based ataxic gait. Approach to Acute •Toxic ingestion •CNS Infections (rhomboencephalitis) •Post-infectious/immune •Acute cerebellar ataxia •Miller-Fisher •ADEM •Myoclonus-opsoclonus •Migraine (Basilar, BPV) •Trauma •Vascular •cerebellar hemorrhage, PCA stroke) •Genetic •Episodic Ataxia 1/2 •Dominant recurrent ataxia •MSUD •PD deficiency Childhood ataxia Chronic/Progressive Investigations: •Urine toxicology screen, drugs levels, CBC, LFTs, lytes •LP: CSF cell counts, protein, glucose, bacterial culture ± PCR testing for varicella, mycoplasma pneumonia or other viruses •Neuroimaging (CT head; MRI with and without gadolinum to rule out structural, demyelinating and infectious etiologies •Metabolic workup for IEM Approach to Childhood ataxia Acute Chronic/Progressive •Neoplastic •Cerebellar astrocytomas •Cerebellar hemangioblastomas •Medulloblastoma •Ependymoma •Congenital malformation •Cerebellar aplasia •Dandy-Walker malformation •Chiari malformation •Hereditary ataxia •Autosomal dominant •Machado-Joseph •Olivopontocerebellar •Autosomal recessive •Abetalipoproteinemia •Ataxia-telengiectasia •Fredreich ataxia •X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy Outline Febrile seizures Afebrile Seizures (Childhood epilepsy syndromes) Headaches Ataxia Hypotonia Approach to Hypotonia Case 6 : 6month old baby boy who was admitted on the ward for FTT and feeding difficulties. Neurology consulted by pediatric’s team who was concerned about the gross motor development of this baby. At 6months, he still cannot support his head, is not sitting, even with support. On exam, high prominent forehead, narrow bifrontal diameter, downslated fissures, almond-shaped eyes, downturned corners of the mouth, micrognathia, dysplasic ears and diminished spontaneous activity of limbs; profound axial and appendigeal hypotonia. Reflexes bilaterally symmetrical 2+, upgoing plantars. No fasciculations. No muscle atrophy. Approach to Hypotonia Central Nervous System Spinal Cord Anterior Horn cell Peripheral Nerve Neuromuscular junction Muscle Approach to Hypotonia Central Nervous System •Benign congenital hypotonia •Genetic syndromes (Prader-Willi, trisomies) •Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy •Cerebral malformations •Cortical migration abnormalities (lissencephaly, schizencephaly) •Inborn errors of metabolism (leukodystrophies) •History (traumatic birth HIE) •Seizures •Cognitive delay •Dysmorphism •Hemiparesis •Hyperreflexia •Limb spasticity Approach to Hypotonia Spinal cord •Trauma •Spinal cord ischemia Approach to Hypotonia Anterior Horn Cell •Spinal muscle atrophy •Neonatal poliomyelitis •Profound weakness •Areflexia •Feeding difficulties •Respiratory difficulties •Tongue fasciculations •No sensory deficits •Alert, interactive Approach to Hypotonia Peripheral Nerve •Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies •Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy •Familial dysautonomia syndromes •Giant axonal neuropathy •Inborn errors of metabolism •Distal > proximal weakness •Hyporeflexia •Facial weakness unusual •Sensory deficits Approach to Hypotonia Neuromuscular Junction •Infantile botulism •Transient neonatal myasthenia gravis •Congenital myasthenia gravis •Generalized weakness •Fatiguability •Hyporeflexia •Feeding problems •Respiratory compromise •Ptosis Approach to Hypotonia Muscle •Congenital myopathy •Congenital muscular dystrophy •Syndromic and nonsyndromic •Congenital myotonic dystrophy •Metabolic myopathy •History of poor fetal movement/polyhydramnios •Proximal muscle weakness •Hyporeflexia •Feeding problems •Respiratory compromise •Facial diplegia •Arthrogryposis/bilateral club feet •Other organ involvement (ex. Heart in Pompe disease) Approach to •Head/spine imaging Hypotonia •Genetic testing •Karyotype Central Nervous System •Prader-Willi (methylation 15q11-13) •SMA testing Spinal Cord •CSF evaluation •EMG/NCS •Muscle/nerve biopsy •Tensilon testing •Metabolic w/u: •Lactate/pyruvate •Plasma a.acids Anterior Horn cell Peripheral Nerve •Urine organic acids •Acyl carnitine profile Neuromuscular junction Muscle •VLCFA References Febrile seizures: clinical practice guideline for the long-term management of the child with simple febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2008 Jun;121(6):1281-6. Stafstrom CE. (2009) Severe epilepsy syndromes of early childhood: the link between genetics and pathophysiology with a focus on SCN1A mutations. J Child Neurol. 2009 Aug;24(8 Suppl):15S-23S. DiMario FJ Jr.(2006) Paroxysmal nonepileptic events of childhood. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006 Dec;13(4):208-21. Fenichel GM (2005). Clinical Pediatric Neurology – A signs and symptoms approach. Guberman A and Bruni J (1999) Essentials of Clinical Epilepsy. Chapter 3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, Hirtz D, Yonker M, Silberstein S; American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee; Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004 Dec 28;63(12):2215-24. Review References To download protocols from MUHC portal