Burden of Malaria and other Infectious Diseases in the

advertisement

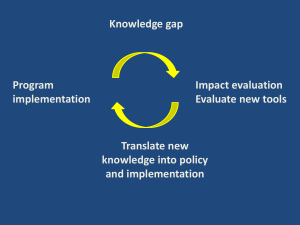

Burden of malaria and other infectious diseases in the Asia-Pacific Ravi P. Rannan-Eliya Institute for Health Policy Sri Lanka Disease Burden 1 Disease burden in DALYs – Developed vs. developing regions (2010) 2 Composition of disease burden – Developed vs. developing regions (2010) 3 Distribution of disease burden in South-East Asia (2010) 4 Distribution of disease burden in South-East Asia (2010) 5 Malaria burden in Asia-Pacific 6 Status of malaria control and elimination, Asia-Pacific 2013 7 Malaria cases and deaths, Asia-Pacific 2012 • 2.2 billion at risk, 32 million cases, 48,000 deaths (2012) – 8% of global deaths, but 67% of global population at risk – Including most of the largest country burdens – India, China, Bangladesh, Viet Nam 8 Artemisinin resistance, Greater Mekong Global hotspot for artemisinin in SE Asia • Linked to weak health systems, high degree of reliance on private/informal provision, high levels of prevalence • Continued production of artemisinin monotherapies, esp. in India • Major risk to global malaria eradication 9 Economic impact of malaria and other diseases 10 Impact of malaria on households and nations Prior to HIV/AIDS, malaria had the largest economic and social impact of any infectious disease in Asia-Pacific. Effects include: • Families – Direct impact on ability to work and function – Direct costs of medical treatment frequently impoverished – Indirect costs of looking after sick patients • Nations – Prevented settlement and use of affected agricultural land, e.g, Cambodia, Sri Lanka – Barrier to foreign investment and tourism • Best estimates of net impact: – Reduces GDP growth by 1-2% in affected countries 11 Health financing and expenditures on malaria and infectious diseases 12 Sources of financing in health systems, Asia-Pacific countries 2010 13 Financing levels by source of funding, by income level within Asia-Pacific 2012 Grouping Per capita health expenditure (USD) Public health expenditure (% of GDP) Private health expenditure (% of GDP) Total health expenditure (% of GDP) External financing (% of total health expenditure) 71 1.6 3.6 5.0 14.1 Lower middleincome countries 166 2.3 2.2 4.5 11.5 Upper middleincome countries 514 2.7 1.7 4.4 0.6 3,228 5.8 2.9 8.3 0.0 Asia-Pacific Low-income countries High income countries • • • Poorest countries with highest malaria burden have least capacity to finance healthcare, in particular to raise public funds Private financing (% GDP) does not grow with GDP per capita External financing significant in poor countries, but fungibility is substantial 14 Distribution of out-of-pocket/private spending by income levels in high burden countries 15 How much is spent on specific diseases? • Short answer = We usually don’t know • WHO, GFATM and others collect data on specific diseases, but data only reliable for external financing – Efforts uncoordinated, duplicative, inconsistent – Typically fails to cover spending by government and private sources for treatment within general health services – Significant burden created for countries from multiple, uncoordinated expenditure reporting requirements, with little benefit – Domestic financing may be 100-300% more than reported for many countries, e.g., malaria in Bangladesh, Solomon Islands • For malaria and many other diseases, unreported domestic spending is likely to be significant – Potential to use increased awareness of current spending levels to increase domestic financing 16 Progress towards disease expenditure tracking 2011-14 • Agreement by international agencies to use health accounts as basis for tracking disease expenditures • Decision by GFATM to support countries to use health accounts (disease accounts) to track and report spending Asia-Pacific • Significant national capacities to produce health accounts, but only few have disease accounts currently – Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand • Efforts by OECD and regional networks to share expertise, but underfunded • Potential new initiative by GFATM to give partial support to some countries 17 Bangladesh Disease Accounts MOHFW Facility Expenditure Per Capita by Age and Condition (Tk) 25 20 15 10 5 0 0 1-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95+ Acute respiratory infections Benign neoplasms Cardiovascular disease Chronic respiratory diseases Diseases of the digestive system Congenital anomalies Endocrine & metabolic disorders Diabetes mellitus Genitourinary diseases III-defined conditions & other contacts Infectious & parasitic diseases Injuries Malignant neoplasms Maternal conditions Mental disorders Musculoskeletal disorders Neonatal causes Nervous system and sense organ disorders Nutritional deficiencies Oral health Other anaemias and blood/immune disorders Skin diseases Unspecified abnormal clinical & laboratory 18 Conclusions 19 Prospects for increasing financing for target diseases in high burden countries • High burden countries = Poorest countries – Least able to mobilize new funding – Case for regional and global solidarity • Private financing dominant, but difficult to capture and mostly serves non-poor – High burden countries have weak capacity to organize financing or to regulate private providers – General global consensus that out-of-pocket spending must be reduced because of link to impoverishment and barriers to access • External financing important for many countries, but additionality is not 100% – Some crowding out today of domestic funding – But governments generally underestimate their actual financial costs 20 Conclusions • Disease and economic burden justify attention to malaria in Asia-Pacific after HIV/AIDS, TB. • Cost-effectiveness of available interventions, economic impacts and potential losses from malaria resurgence justify prioritization of spending today at regional level • Highest burden countries least able to finance efforts, but growing incomes in Asia-Pacific and large size of countries points to increasing domestic mobilization in those that can afford, and increased reliance on domestic public financing • Issue of fungibility of aid and challenge of maintaining domestic financing commitments in elimination countries suggests potential for using external and new funding to incentivize greater domestic government spending efforts 21