Abdominal Compartment Syndrome & Renal Failure

advertisement

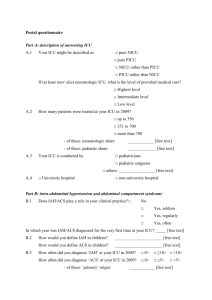

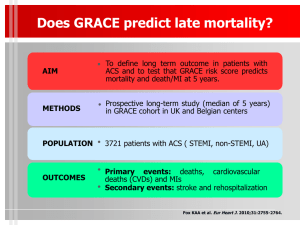

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome & Renal Failure PEGGY BEELEY, MD O C T O B E R 1 2 TH, 2 0 1 1 Case 49 yo female admitted with cirrhosis and worsening ascites, Cr 2.8 on admission Had diagnostic paracentesis on admission negative for infection Nephrology consulted. Urine sediment c/w ATN with prerenal component suspected Large volume paracentesis of 3.5 L, next diagnostic tap 4 days later was bloody Cr began to climb, bladder pressure was 32-34 mmHg Large volume paracentesis removed 5 L of bloody fluid, bladder pressure 24 mmHg Cr continued to climb, comfort care measures instituted Patient died Objectives Understand pathophysiology of increased intraabdominal pressure (IAP) and organ failure Learn current methods used in determining IAP Learn limitations of such measurements Evaluate literature for use in cirrhotic patients with ascites ACS: Importance in Hospitalist Medicine Occurs in Patients with rapid volume resuscitation (especially in early goal directed therapy for sepsis) Acute formation of ascites In visceral edema May see this more commonly as we see more acutely ill patients High mortality rate associated with ACS Early recognition leads to improved outcomes History of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) Wendt in 1876 the association of intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and renal dysfunction Recognized as a complication in trauma surgery in 1970s Most early descriptions in trauma literature Now recognized as occurring in critically ill patients and in medical conditions Not universally appreciated across different specialties Not much in nephrology literature by my search Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) Rotondo, et al 1983 recognized that IAH as cause of multi-organ failure ↓preload, ↑afterload and extrinsic compression leads to decreased oxygen delivery in abdominal organs Resultant pressure-volume dysregulation syndrome is known as ACS World Society of the ACS The mission of the WSACS is to promote research, foster education, and improve the survival of patients with intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and/or abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) All who have an interest in the diagnosis, management, and/or treatment of IAH / ACS are invited to join the Society. Definitions Normal intraabdominal pressure (IAP) is <5-7 mmHg Upper limit of normal IAP is 12 mmHg > 12 mmHg is Intraabdominal Hypertension (IAH), must be sustained to meet criteria Grade I is 12-15 mm Hg Grade II is 16-20 mm Hg Grade III 21-24 mm Hg Grade IV > 25 mm Hg ACS : sustained IAP >20 mmHg that is associated with new organ dysfunction Morbidly obese and pregnant women may have pressure as high as 10-15 mmHg without adverse sequela Primary vs. Secondary ACS Primary ACS injury or dz within abd or pelvis Surgical interventions often needed Secondary ACS Often from conditions outside the abd or pelvis., e.g. burns, sepsis Recurrent ACS Condition in which ACS redevelops following previous surgical or medical treatment of primary or secondary ACS Mechanism of Organ injury in ACS Ischemia, either venous or arterial Release of vasodilatory substances As ischemia progresses capillary integrity fails and leads to extravasation of fluid, lytes, proteins Increased distance between tissue and capillaries Viscous cycle compromises organ viability Renal Injury due to ACS First oliguria Then rise in serum creatinine Rise of < 0.3 mg in creatinine = AKI Rise of more that 0.3 mg = ARF As oliguria worsens no amount of fluid resuscitation will help ATN occurs upon reperfusion, usually by abdominal decompression Cirrhosis and Ascites in ACS Mentioned in several articles as potential cause of ACS Removal of ascites in IAPs > 18.4 mmHg does improve renal function Intravasc volume may improve renal function in chronic ascites where ACS it does not Most cirrhotics tolerate > 15 liters of ascites w/o renal failure or organ ischemia Abdominal wall compliance remains if fluid accumulation is slow Renal Failure in Cirrhotics with Ascites IAH/ACP Hepato-renal Oliguria Oliguria Often looks like ATN Bland urine sediment Acute ischemia to kidney Vasodilators: Lactate and adenosine Elevated ADH, usually increased more than twice baseline Slowly progressive ischemia Vasodilator: Nitric Oxide, ?prostaglandins Salt conserving state, elevated ADH Incidence of IAH and ACS in Critically ill Multicenter prospective study of 265 patients admitted to ICU 32% IAH 4% ACS 53% normal IAP IAH was strongly associated with multi-organ dysfunction and nearly all had ARF Another prospective study of 706 pts at U of Miami showed an incidence of 2% IAH and 1% ACS in trauma population Malbrain et al, Crit Care Med 2005 ; 33 Hong et al Br J Surg 2002: 89 Associated signs and organ failure in ACS Hypovolemic shock ↓ SBP,↓ pulse pressure, lactic acidosis, tachy Increased core to peripheral temp grad, weak pulses, abnormal mentation Acute kidney injury/acute renal failure Acute respiratory failure Hypoxia & hypercarbia Increased peak airway pressures ↓tidal volume Acute hepatic failure ↑LFTs, coagulopathy Estimating & Measuring IAP Bladder pressure NGT pressure Condom Cath measurement Gastric tonometry Direct measurements by laparoscopy Direct measurement in femoral vein or inferior vena cava Validity of Bladder Pressure as an estimation of IAP 37 patients undergoing laparoscopy Measured direct IAP with laparoscopic insufflation Simultaneously measured bladder pressure At O ml bladder volume 50 ml, 100 ml, 150 ml, & 200 ml 1110 data points of bladder pressure at various IAPs were collected Findings showed high correlation of bladder pressure to IAP (R2 = 0.68) Least bias with the 50 ml instillation Fusco et al, J of Trauma,: 2001: 50 Measuring Bladder Pressure Cheatham et al J Am Coll Surg 1998 Other Causes of Elevated IAP Estimates in Bladder Pressure Central Obesity Pregnancy Not reliable in the following Low intrinsic bladder compliance bladder trauma Pelvic hemorrhage Overestimated in these conditions Therapeutic Interventions Laparotomy with temporary closure to enlarge peritoneal space Non-surgical Catheter drainage Therapeutic paracentesis Dialysis Neuromuscular blockage Prokinetic agents if intestinal distension is present. Control underlying etiology (hemorrhage, ascites) No prospective RCT have been done to compare efficacy of Non-surgical decompression vs. surgical Nonoperative Management of IAH & ACS Evacuate intraluminal contents Evacuate intraabdominal space-occupying lesions Improve abdominal wall compliance Optimize fluid administration Optimize systemic and regional tissue perfusion Cheatham, World J Surg 2009 33 Case 49 yo female admitted with cirrhosis and worsening ascites, Cr 2.8 on admission Although patient did have a slowly worsening ascites, she develop hemorrhage after paracentesis High risk patient Acute on chronic elevation in IAP could have led to ACP Therapeutic tap seemed reasonable, did we not take off enough? May have been Hepatorenal but bladder pressure of 32 made ACP a compelling diagnosis Recommendations Consider ACS in your differential diagnosis, especially after rapid fluid resuscitation Acute ACS is generally a surgical disease with abdominal decompression If recommended by consultant, ask to review rational Remember to do albumin replacement in large volume paracentesis Group did not come to clear consensus about how to use bladder pressures in cirrhotic patients with ascites.