Week1

advertisement

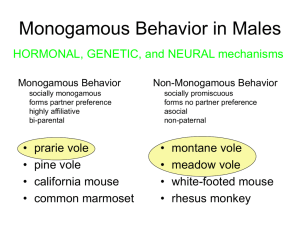

Tinbergen 1963 Alcock’s paraphrase of Tinbergen • How does the behavior promote an animal’s ability to survive and reproduce? • How does an animal use its sensory and motor abilities to activate and modify its behavior patterns? • How does an animal’s behavior change during its growth, especially in response to the experiences that it has while maturing? • How does an animal’s behavior compare with those of other closely related species, and what does this tell us about the origins of its behavior and the changes that have occurred during the history of the species? Figure 1.1 The monogamous prairie vole Figure 1.2 The brain of the prairie vole is a complex, highly organized machine Figure 1.3 A gene that affects male pairing behavior in the prairie vole Figure 1.7 Testing the hypothesis that male monogamy is influenced by a single gene Figure 1.4 The evolutionary relationships of the prairie vole and six of its relatives Box 1.1 How are phylogenetic trees constructed and what do they mean? Conroy and Cook 2000 Figure 1.5 The possible history behind monogamy in the prairie vole Figure 1.11 Artificial selection causes evolutionary change as predicted by the theory of natural selection Figure 1.12 A test of whether dogs are more sensitive to signals from human beings than are hand-reared wolves Figure 1.13 Hanuman langur females and offspring Figure 1.14 Male langurs commit infanticide Figure 1.15 Variation in suicidal tendencies in a make-believe lemming-like species Adaptation An adaptation is, thus, a feature of the organism, which interacts operationally with some factor of its environment so that the individual survives and reproduces. (Bock, 1979, p. 39) Adaptation "The ground rule -- or perhaps doctrine would be a better term -- is that adaptation is a special and onerous concept that should be used only where it is really necessary . . . A frequent practice is to recognize adaptation in any recognizable benefit arising from the activities of an organism. I believe that this is an insufficient basis for postulating adaptation and that is has led to some serious errors. A benefit can be the result of chance instead of design. The decision as to the purpose of a mechanism must be based on an examination of the machinery and an argument as to the appropriateness of the means to the end. It cannot be based on value judgments of actual or probable consequences." (Williams, 1966) Adaptation "The sutures in the skulls of young mammals have been advanced as a beautiful adaptation for aiding parturition, and no doubt they facilitate, or may be indispensable for this act; but as sutures occur in the skulls of young birds and reptiles, which have only to escape from a broken egg, we may infer that this structure has arisen from the laws of growth, and has been taken advantage of in the parturition of the higher animals." (Darwin, 1859, p. 197) Adaptation "If whole populations are adaptive, it seems possible that adaptations producing beneficial death of an individual -- death for the benefit of the population might evolve . . . It may be concluded from these data that . . . natural selection operates upon the whole interspecies system, resulting in the slow evolution of adaptive integration and balance. Division of labor, integration, and homeostasis characterize the organism and the supraorganismic interspecies population. The interspecies system has also evolved these characteristics of the organism and may thus be called an ecological supraorganism." (Allee et al., 1949) Adaptation Benefits to groups can arise as statistical summations of the effects of individual adaptations. When a deer successfully escapes from a bear by running away, we can attribute is success to a long ancestral period of selection for fleetness. Its fleetness is responsible for its having a low probability of death from bear attack. The same factor repeated again and again in the herd means not only that it is a herd of fleet deer, but also that it is a fleet herd. (Williams, 1966) Adaptation Let us now consider the individualistic claim that “virtually all adaptations evolve by individual selection.” If by individual selection we mean withingroup selection, we are saying that A-types virtually never evolve in nature, that we should observe only S-types. This is a meaningful statement, because it identifies a set of traits that conceivably could evolve, but does not, because between-group selection is invariably weak compared to within-group selection. Let us call this valid individualism. . . . If by individual selection we mean the fitness of individuals averaged across all groups, we have said nothing at all. Since this definition includes both within- and between-group selection, it makes ‘individual selection’ synonymous with ‘whatever evolves’ including either S- or Atypes. It does not identify any set of traits that conceivably could evolve but does not. Let us therefore call it cheap individualism. (D.S. Wilson, 1989)