Evolution

advertisement

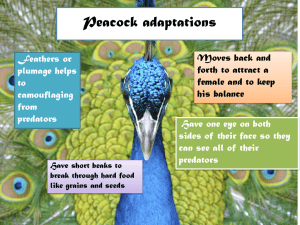

Behavioural Adaptations for Survival BIOL 3100 Mobbing behaviour • When a predator is spotted, birds, like chickadees, will give a specific alarm call or mobbing call. • When heard, all individuals present come in to investigate and attack the intruder (hawk, owl) When played back chickadee mobbing calls and other chickadee vocalizations, significantly more birds approach the speaker and display mobbing behaviour during mobbing call playback Thus, chickadee mobbing calls carry meaning for at least 10 other avian species Variation in the mobbing call signifies different predators The different warnings help flock mates grasp the relative threat of the intruder Flying owls, hawks and flacons provoke a highpitched “seet” call Small raptors, like saw whet owls and American kestrels (which are the biggest threat) provoke more “dees” at the end of the call and elicit a larger Perched predators evoke a loud “chickadee” call Crazier still: Same behaviour is exhibited by gulls when a predator, such as a raptor (or researcher) is present A student of Niko Tinbergen’s, Hans Kruuk, was interested in examining the ultimate causes of mobbing behaviour in black-headed Gulls Question: Is mobbing an adaptive behaviour and a product of natural selection? Hypothesis: Mobbing distracts certain predators, reducing the chance that they would find the mobbers’ offspring, boosting the fitness of mobbing parent gulls So, if mobbing behaviour is adaptive, why don’t 100% of the parents mob predators 100% of the time? In other words, why doesn’t the mobbing phenotype “win out” 3 constraints on adaptive perfection 1) Failure of appropriate mutations to occur. Evolutionary constraints on adaptive perfection can arise from failure of appropriate mutations to occur, which will prevent selection from keeping up with environmental change. Thus, maladaptive or nonadaptive traits may persist. (e.g. ground squirrels in the arctic, moths) 2) Pleiotropy. Most genes have multiple developmental effects, not all of which are positive. If overall negative, selection will act against that gene; if overall positive, selection will maintain the trait, though there may still be negative consequences. 3) Coevolution. Interaction of different species that influence each others fitness. Each species changes in response to selection pressure imposed by the other, resulting in an evolutionary arms race. So back to the gulls… • There will be constraints on adaptive perfection, meaning that we should observe variation in mobbing behaviour • In addition, if the trait is adaptive, then the trait either (a) spread through the population in the past and has been maintained by natural selection or (b) is currently spreading relative to alternative traits • Thus, mobbing should confer a fitness advantage (i.e., individuals that mob should have higher reproductive success) One approach to test whether a trait is adaptive is to take a cost-benefit approach in which different phenotypes are analyzed in terms of fitness costs and benefits Benefit: Mobbing prevents offspring from getting eaten, predators forced to spend more time searching for prey Costs: Time and energy expended, getting eaten yourself by the predator California ground squirrels react to hunting rattlesnakes by gathering around it and shaking their tails vigorously to encourage it to depart before being physically attacked by the squirrels. Also have a pretty cool adaptation we’ll talk about on Friday… Species from different evolutionary lineages that live in similar environments and are subject to similar selective pressures may evolve similar traits through convergent evolution In other words, different taxa may find the same solution to the same problem. Though the squirrels do have some antivenom, there are costs to being bitten by a snake Hypothesis: Squirrels should adjust behaviour based on the degree of threat. Test: When rattles of different sized snakes were played back, the squirrels approached the big snake rattle sound more cautiously than the small snakes. Examining the costs and benefits of antipredator behaviour Dilution Effect Observation: Butterflies aggregate in large, densely packed groups around mud puddles on tropic riverbanks, where they suck up minerals from the soil. Hypothesis: Bigger groups are more likely to attract avian predators, but cost offset decreased chance that any one individual will be eaten Test: Examine probability of capture in relation to group size … in this case, the benefits of joining a larger groups substantially outweigh the costs Dilution Effect Is this the reason that mayflies all emerge at the same time so as to effectively lodge in your teeth while biking (or eaten by trout when they emerge from water)? Test: Use nets to capture cast-off skins of mayflies, as well as dead female mayflies, which die naturally after laying their eggs, unless they’re eaten first… Sweeny & Vannote Anti-predator behaviour can also be exhibited through direct attacks on potential pred Have you ever stepped on a wasp nest? Sawfly larvae cluster in balls of ~10 individuals where they feed on eucalyputus leaves, which contain resinous, toxic oils, which they store in special sacs and regurgitate onto attacking ants or birds. If you can’t fight – hide! Canyon treefrogs rely on camouflage for defense from predators, which means they need to pick the right rocks on which to cling tightly and be completely stationary. Cryptic colouration depends on background selection. This Australian thorny devil is very well camouflaged when stationary against bark and debris, but highly conspicuous on a road. The classic example of the peppered moth, Biston betula The classic example of the peppered moth, Biston betula In Great Britian and the US, the melanic form of the peppered moth was once extremely rare, but almost completely replaced the salt-and-pepper form from 1850-1950. As industrial soot darkened the colour of forest tree trunks in urban areas the whitish moths became more conspicuous and were subsequently eaten, removing those genes And yes, this experiment is still valid. Observational study: examining the natural frequency of black and white morphs in response to changing conditions Experimental study 1: Place moths on different trees (and on different locations on trees) and examine predation rates. Moths of both types were less likely to be found and removed by birds on limb joints, but overall, Orientation is also important. Catocala relicta moths usually perch head-up with with whitish forewings over its body on white birch and other light-barked trees. Is this behaviour adaptive? If so, predators should overlook moths more often when they perch on their favorite substrate, in their preferred orientation. Experimental study 2: Images of moths on different backgrounds and in different resting positions are shown to a captive blue jay, which is rewarded for detecting a moth. Jays saw moths 10-20% less often when the moths were on light-coloured bark. Birds were especially likely to overlook moths when they were oriented head-up on birch bark. Some species, like these grasshoppers (B) use large black and white patches to disrupt predators’ edge detectors, creating false edges. On the other hand, the black horse lubber grasshopper (C) emphasizes their outline to make them more conspicuous (aposomatic colouration) California ground squirrels chew on cast rattlesnake skins then lick their fur. Wh When given captive rattlesnakes a chance to investigate filter paper, some of which had been rubbed on a squirrel then subsequently rubbed on snake skin, and other paper that just had been rubbed on a squirrel – the rattlesnake spent twice as much time inspecting pure squirrel-scented targets. But sometimes it pays to be conspicuous...