Justice at sea - Development Studies Association

advertisement

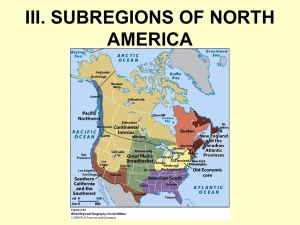

Vasudha Chhotray, UEA DSA Conference, London, 2012 Fishing jetty Kharnasi village Mahakalpada block Kendrapara district Odisha INDIA 2 Methodology Qualitative. Inductive. 10 exploratory interviews around justice in Kharnasi. Four framing questions: - What aspects of resource use do you find just or unjust? - Who/what is responsible for it? - Which institution/set of actors can do something to redress this situation (if unjust)? - What can you do about it? 5 Focus Group Discussions in Kharnasi: male and female fishers; boat owners; crew members; boatmakers; shopkeepers 35 Key Informant Interviews: Odiya and Bengali fishers in Kharnasi and neighbouring villages, fisher leaders, trade union members, cooperative presidents, environmentalists, fisheries and forest department officials (past and present) active in Kendrapara district and coastal Odisha 3 4 A ‘prelude’ to environmental justice What comes before equality and fairness? Legitimacy of presence and acknowledged rights of fishing in this particular sea Filters for environmental justice : caste, ethnicity, identity, class, territory and citizenship Odiya environmentalism and eco-nationalism (Sharma, 2012) Meaning of ‘justice at sea’ for fishers inseparable from such filters Political struggles for justice removed from everyday material struggles 5 Relevant conservation debates Nation state arch provider of a ‘community for justice’ (Dobson, 1999) Conservation and rights of citizenship (right to be informed, rights of settlement) (Jayal, 2010) Local residence and legitimate claims to territory (Baviskar, 2003) ‘Longstanding’ customary association with place/resource use; passage of uncertain length of time as ‘traditional’ (Skaria, 1999; Das, 2011) Conservation is about how ‘nature ought to look’ (Neumann, 1998) 6 Turtle conservation in Odisha Olive Ridleys, Odisha and the global conservation spotlight Arribadas (arrival) in December-January each year Alarming turtle mortalities off Odisha coast in the 1970s Passionate nationwide environmental campaigns, state scientific research and keen personal interest by PM Indira Gandhi 7 Principal measures for turtle conservation in Odisha State Olive Ridleys declared an ‘endangered species’ in Schedule I of Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 Fishery regulation through OMFRA (Odisha Marine Fisheries Regulation Act), 1982 Emphasis on ‘sustainable’ fishing; different zones for different crafts Only ‘non-mechanised “traditional” boats’ allowed within 5km of shore Notification of Gahirmatha as a marine sanctuary in 1997, blanket fishing ban Protection of turtles at two other major nesting sites (Devi and Rushikulya river mouths) through seasonal fishing bans (November-May) Use of TEDs (turtle excluder devices) mandatory for trawlers NGO Operation Kachhapa (OpK), a turtle conservation initiative launched in 1989-90 under the aegis of the Wildlife Society of India 8 Conflict over marine fishing Conservationists accuse state for sponsoring ‘overfishing’ Concern over ‘unsustainable rise’ in mechanised fishing: 250% in 25 years (Greenpeace, 2008) State has not been productivist enough, argue fishers and officials Negative comparisons with Kerala (Sinha, 2012) No investment in deep sea fishing, EEZ Excessive exploitation of near shore waters and poor patrols produce turf wars 9 The fishing castes and communities of Odisha Nolias in Gopalpur, Ganjam Odiya fisherman near Paradip, Jagatsinghpur 10 Ethnicity and fishing techniques Odiya woman with mugura (bamboo and stick basket) in Kendrapara district FRP gill net boats owned by Bengali fishers in Kharnasi jetty 11 ‘Then gradually these Bangladeshis spread to the entire Odisha coast. The Odiya fishermen would never go to the sea for fishing. They would fish at the river mouth. But after the influx of the Bengali fishermen, they started the motorised boats and after overfishing in the river, they started going to the sea’ (Sankhanad Behera, kaibarta leader, founder of Kalinga Karnadhar Fishing Society and environmentalist). ‘Later on due to the rising population of Bangladeshi immigrants and declining catch in estuaries in the late 1970s, they (Odiyas) could not fish inside the estuarine and riverine areas, so they were kind of forced to go to the sea’ (Biswajit Mohanty, Operation Kachappa). 12 Bengali immigration and Odiya environmentalism No pre-existing ‘commons’ to be defended Bengali fishers’ right to fish in this particular sea in contention Struggle over territory linked to painful episodes in history: partition of 1947, creation of Bangladesh in 1971 (Chatterji, 1997) Territory no mean motivator of national allegiance; ‘eco-nationalism’ and ‘econaturalism’ (Sharma, 2012) Rise of right-wing Odiya environmentalism: territory, nation, legality 13 Chief allegations Ruining marine ecosystem, depleting fish stocks, killing turtles ‘Entire fisheries in the state has collapsed because of these Bangladeshis only’ Promoting infringement of Indian sovereignty, territorial waters Harbour illegal immigrants Invite relatives from Bangladesh during fishing season 14 Dominant narratives within Odiya environmentalism Crude typology of ‘legitimate’ (from West Bengal in the 1940s) and illegitimate settlers (from former East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, especially after 1971) No proper settlement for ‘hordes of refugees’ that came to Odisha Impression of Bengali prosperity at the expense of Odiyas Partial histories Refugee journeys into India from Bangladesh a continuous process since 1947 Low caste/class immigrants, history of oppression Adversely affected by refugee politics, disastrous state policies of rehabilitation Patchy experiences with settlement; compelling factors Strong feelings of association with Kharnasi village; distinctive territoriality 15 Controversy over infiltration 1998 public law suit, 2005 court directive to ‘identify infiltrators’ 2005 episode of identification of 1551 ‘infiltrators’; deportation attempts halfhearted and unsuccessful Disbelief, anger amongst Bengali settlers (who are Indian citizens) Mixed reactions amongst Odiya fishers and elites Crude pro-caste, nation and anti-refugee rhetoric, but no sustained attempt at deportation 16 Justice at sea Sea view from Kharnasi jetty Marine police station, Kharnasi 17 Technique, tradition, turf Who is killing the turtles? Decimation of 'traditional’ fishing techniques: to be traditional is to be the least culpable Convoluted hierarchy of blame Ethnic/caste/class branding of nets and technologies Gill netting versus trawling Class differentiation 18 Following fishers Flagrant, unambiguous acknowledgement of transgression Bengalis-Odiyas commonly aggrieved Passage to sea State vested interest in status quo Marine policing difficult Power struggles at sea Corporeal injustice 19 Everyday struggles for justice Sea fishing: risky, lucrative Weakest links in the chain Capitalisation and vulnerability Chains of exploitation, despair Despair at lack of ‘alternatives’ 20 Political struggle for justice Odisha Traditional Fishworkers Union (OTFWU); collective resistance Negative attention to ethnic origins of leaders ‘This is the irony….it is a traditional association of Odisha but the office bearers are Bengali and Telugu.’ (Biswajit Mohanty, OpK) Tradition, time and technology Personal politics Credibility crisis with poorest fishers of all backgrounds 21 Conclusion Prelude to specific questions of equality and fairness for immigrant Bengali fishers Rise of right wing Odiya environmentalism: caste, ethnicity, territory, even citizenship Filters for just conservation (evidence of belonging, residence, tradition) Markers of social identity, fishing technologies, environmental culpability Absence of private property at sea; collective claims undermined within negative environmentalism Disjuncture between fishers’ (leaders) politics and concrete everyday struggle for justice 22 References Baviskar, A. 2003 ‘States, communities and conservation: The practice of Ecodevelopment in the Great Himalayan National Park’, in V.K. Saberwal and M. Rangarajan (eds.) Battles over nature: Science and the politics of conservation, Permanent Black, Delhi. Chatterji, J. 2007 The spoils of partition: Bengal and India, 1947-67, Cambridge University Press, New Delhi. Das, P.D. 2011 ‘Politics of participatory conservation: A case of Kailadevi sanctuary, Rajasthan, India’, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, London. Dobson, A. 1999 Justice and the environment: Conceptions of environment sustainability and theories of distributive justice, Oxford University Press, USA. Greenpeace 2008 ‘Odisha: Turning seas of trouble into seas of plenty’ Jayal, N.G. 2010 ‘Balancing political and ecological values’, Environmental Politics, 10:1, 65-88 Neumann, R. P. 1998. Imposing wilderness: struggles over livelihood and nature preservation in Africa, University of California Press, Berkeley. Saberwal, V. and Rangarajan, M. 2003 ‘Introduction’ in V.K. Saberwal and M. Rangarajan (eds.) Battles over nature: Science and the politics of conservation, Permanent Black, Delhi Salagramma, V. 2006 ‘Trends in poverty and livelihoods in coastal fishing communities of Odisha state, India’, FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 490 Sharma, M. 2012 Green and saffron: Hindu nationalism and Indian environmental politics, Permanent Black, Ranikhet. Sinha, S. 2012 ‘Transnationality and the Indian Fishworkers’ Movement, 1960s-2000’, Journal of Agrarian Change, 12: 2,3, 364-389. Skaria, A. 1999 Hybrid histories: Forests, frontier and wilderness in western India, Oxford University Press, New Delhi. 23