Nineteenth-Century Women and Authorship

advertisement

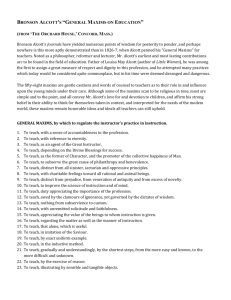

Nineteenth-Century Women and Authorship The Case of Louisa May Alcott Nineteenth-Century Authorship ► Not a true profession for gentlemen—or ladies. ► Ideology of “the Angel in the House” (Coventry Patmore) and “True Womanhood” kept women out of the public sphere and in the private sphere. ► To step outside domesticity for reasons of ambition threatened one’s reputation as a “womanly woman” ► Writing for necessity—to earn a living—was acceptable for women authors. Socially Acceptable Outlets for Women’s Writing ► Writing for church papers ► Writing for reform (abolitionist tracts, prison reform, temperance). Example: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) ► Writing on domestic issues: Catharine Beecher’s The American Woman’s Home (1869) ► Woman’s fiction, also called “domestic fiction” or “sentimental fiction” Domestic Fiction, 1830-1865 Young girl who is orphaned or otherwise forced to go out into the world on her own. ► Heroine embodies one of two types: The angel in the house The practical woman ► These contrast with two types who fail to help or sometimes torment her: The passive woman (incompetent, cowardly, ignorant; often the heroine's mother is this type) The "belle," who suffers from a defective education. ► Heroine denial. must learn self-mastery and self- Domestic Fiction, continued ► Immersion danger. ► Marriage in feeling (rather than reason) a Reforming the bad or "wild" male, as in Augusta Evans's St. Elmo (1867) Marrying the solid male who already meets her qualifications. ► The novels may use a "language of tears" that evokes sympathy from the readers. Examples Cummins, The Lamplighter (1854) ► Susan Warner, The Wide, Wide World (1850) ► Warner’s book sold well over 100,000 (and some sources say 1,000,000) copies in 1850 when The Scarlet Letter sold 10,000. ► Maria Hawthorne’s Reaction ► Hawthorne to his publisher, 1855: “America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash–and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed. What is the mystery of these innumerable editions of the ‘Lamplighter,’ and other books neither better nor worse?–worse they could not be, and better they need not be, when they sell by the 100,000.” Alcott’s Work as “Alcott” ► Flower Fables (written for Ellen ► Little Women (1868) and Good Wives (1869) An Old-Fashioned Girl (1870) Little Men (1871) ► ► Emerson) ► “Transcendental Wild Oats” (1873) ► Work, a Story of Experience ► Eight Cousins (1875) and Rose in Bloom (1876) Jo’s Boys (1886) ► (1873) Alcott’s Work as “A.M. Barnard” ► “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment,” $100 prize from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1862. “V.V.; or, Plots and Counterplots” ► The Mysterious Key, 1867 ► “A Marble Woman: or, The Mysterious Model,” The Flag of Our Union, May-June 1865. ► “Behind a Mask: or, A Woman’s Power,” published in The Flag of Our Union on October 13, 20, 27, and Nov. 3, 1866 ► Alcott on Alcott ► On her children’s fiction: “Moral pap for the young.” ► On her thrillers: “I think my natural ambition is for the lurid style. . . . And my favorite characters! Suppose they went to cavorting at their own sweet will, to the infinite horror of dear Mr. Emerson [?]”