Based Practice: It`s more than just research

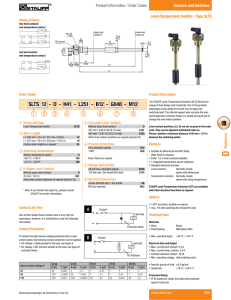

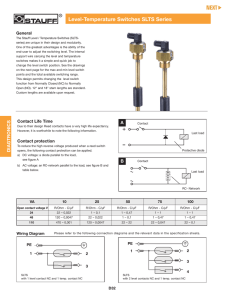

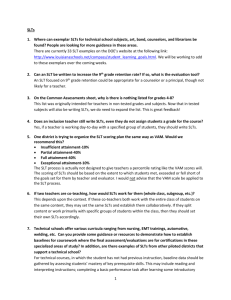

advertisement

Juliet Goldbart Research Institute for Health & Social Change, Manchester Metropolitan University, U.K. Derived from medical research and thinking, (e.g. Sackett et al, 2000). Now applied to education, health and social care, criminal justice policy and practice etc. The integration of best available research evidence with professional expertise and service user values. BUT the focus always seems to be on the research! Two inter-related projects: Communication and people with the most complex needs: what works and why this is essential? Funded by Mencap and Dept. of Health Valuing People team. Survey of U.K. speech & language therapists working with children and adults with PMLD. Children and adults with Profound disabilities Severe autism Severe learning disability and challenging behaviour • Survey of intervention literature • Interviews and focus groups with parents and family carers • Email “interviews” via the PMLD Network • Email “interviews” with international group of experts • Data from UK SLT survey • What are the most useful strategies • What are the most useful strategies in communicating with your son or daughter? • What should other people know about your son or daughter’s communication? • What communication strategies help your son or daughter have some participation in the community? We used family members views as a proxy for the views of people with PMLD/CCN. What are the problems with this? What else could we have done? How do you determine what the people you work with think of their education and therapy? • What are the most important strategies that communication partners can use to facilitate successful communication with people with CCN? • What communication skills can people with CCN learn or use to support their community engagement? • What are the most important issues and components in training staff to work with CCN? Interviews, focus groups and email “interviews” with 30 parents and family carers of children and adults mainly with PMLD or SLD and severe challenging behaviour. Email “interviews” with 11 professional experts from Australia, UK and Netherlands, including teachers, psychologists and speech & language therapists. 55 respondents. Selected Aims To determine what communication intervention / therapy approaches are used by UK SLTs working with children and adults with PMLD. To explore SLTs’ rationales for their choice of interventions. Qualitative data, Content Analysed. Literature search found SOME evidence for: Switch-based interventions Intensive interaction Staff (and parent) training Symbolic approaches (for more able people) Creative and narrative approaches Environmental modification Objects of reference Level and Type of Evidence 1a 1b 2a 2b 3a 3b 4 5 Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis of RCTs A single Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) Systematic Review of Cohort Studies A single Cohort Study Systematic Review of Case Control studies or Quasi Experimental studies A Single Case Control Study or Multiple Baseline SSED design Non experimental descriptive studies e.g. correlation studies and other Single Case Experimental Designs Expert opinion, textbooks, “first principles” research Operating switch results in a reliable consequence, teaching intentionality. Intentionality as a step towards intentional communication, e.g. gaining attention (Lancioni et al., 2009) and understanding, making and conveying choices (Lancioni et al., 2006a & b). Evidence: mainly 3b Used by 10.9% of UK SLTs. Based on the responsive, individualised interactions between babies and caregivers. Aims to develop enjoyable interactions, increasing sociability. Devised by Hewett and Nind (e.g. 1998) Evidence, mainly level 3b (e.g. Leaning & Watson, 2006; Samuel et al., 2008; Zeedyk et al., 2009). Used by 85.5% of SLTs. Long history of research supporting the use of symbols for communication for adults with learning disability (e.g. Beck et al., 2009) and children with autism (e.g. Nunes, 2008) Approaches include Makaton, Signalong, PECS, Boardmaker and photographs. Used by 29.1% of SLTs. Relevance for these learners / clients? Many staff “failed to adjust their language to meet service users' needs,” (Healy & Noonan Walsh, 2007). Bloomberg et al (2003) 6 month staff training: limited changes in knowledge and attitude, but improved interactions with clients. Staff can learn a core sign vocabulary, but tend not to use it (Chadwick & Jolliffe, 2009) . Evidence: typically 3b/4 but variable outcomes. Little evidence of sustainability. Used by 27.3% of SLTs. Long tradition of music therapists working with people with LD in a therapeutic manner (e.g. Warner, 2007). Other approaches draw on the parallels between music and language &/or communication (Graham, 2004; Perry, 2003). Evidence: Modest mainly level 4. Multisensory approaches or music are used by 43.7% of SLTs. Language and multisensory props are used to construct a narrative. Social (Ali & Frederickson, 2006) or sensitive stories aim to aid understanding of a social or personal situation. Sensory or multi-sensory stories (Young, 2011) provide the learning opportunities and pleasure of engaging with a story, without the need to understand language. Evidence: modest and some contradictory (e.g. Penne et al., 2012) – level 3b/4 Multisensory approaches or music are used by 43.7% of SLTs. Use of familiar object cues to signal what is about to happen and to offer choices (e.g. Park, 2002). A concrete link into language, through increasingly abstract representations: Index Icon Symbol. Evidence: 4 BUT only one study with equivocal results (Jones et al., 2002). Used by 72.7% of SLTs. Changes made to the environment, providing opportunities for communication or engagement with people, objects and events. “inconsistent effects of Snoezelen® environments on observable behavior, generalization of behaviors, and relaxation” (Botts et al., 2008) Evidence: more research needed (Botts et al., 2008; Stephenson & Carter, 2011). Used by 27.3% of SLTs Way of capturing and sharing information to facilitate interactions by helping less familiar people recognise potentially communicative behaviour (Millar & Aitken,2003) Not an intervention per se, but making the passport involves detailed discussion among significant others and information sharing Evidence: no formal evaluations Used by 30.1% of participants Parents and professional experts agreed: Communication with people with the most complex needs is most successful with familiar, responsive partners who care about the person with whom they are communicating. Parents and experts agreed: • Capturing and sharing information is crucial. • Communication passports and hospital passports quite widely used, more with adults than children and highly valued. • It enabled hospital staff to “see my son as a person” (parent). An absence of findings. • Not widely used in UK. • BUT the approach with the most evidence. • A route into communication including AAC. • Reported by small numbers of parents and experts. • Resources for practitioners are available. Good research and practice needs to be shared. People who know the individual well should be closely involved in training staff. Attitudes & characteristics: Consistent, patient, empathetic, caring, committed, prioritise service users, trustworthy, understand health and behavioural issues, able to form relationships. Knowledge & Skills: Specific approaches; that challenging behaviour may communicate pain. Signing (15 BUT some have reservations and 5 report idiosyncratic use); Photos or symbol books (8); PECS (8 BUT 4 have reservations); High-tech AAC (5); Intensive Interaction (2); Single switches, e.g. BigMack (2); Music Therapy (2); Objects of Reference (1). Are parents aware of all approaches used?? Parents reported informal strategies more often than specific intervention approaches: Taking time to become familiar with the individual, their personality and communication style, Consistency and use of familiar routines, Clear, simple input, Value of music, Opportunities to make choices, A smile and a communication passport are key to community inclusion. Specific interventions recommended: Intensive Interaction (7/11) Objects of Reference/Object or sensory cues (6/11) Creative or narrative approaches (5/11) AAC (to support comprehension and expression, low, light and high tech) (5/11) Hanging Out Programme (3/11) InterAACtion (3/11) Above all: Individualise approaches and keep the individual client at the centre of decision-making. Intervention Research evidence Parent values “Expert” opinion SLT Use Switchbased Mainly 3b Limited support 5/11 support AAC….. Limited 10.9% Intensive Interaction 3b and 4 Limited support 7/11 support Extensive 85.5% Objects One level of 4 only Reference Limited support 6/11 support Extensive 72.7% Attitudes of communication partners are central. Parents may not be aware of interventions used. Parent involvement in staff training and an emphasis on informal strategies would be valued. A range of interventions are valued by professionals, but not all are supported by evidence. Further research is needed in particular on commonly used approaches, including Communication Passports, for which we have little evidence of success. Mencap project report is free at www.mencap.org.uk/all-about-learningdisability/information-professionals/communication Or http://www.netbuddy.org.uk/static/cms_page_media/52/C ommunication.pdf j.goldbart@mmu.ac.uk