Faculty

Jorge A. Marrero, MD, MS

Professor of Medicine

Chief, Clinical Hepatology

Medical Director, Liver Transplantation

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, TX

Activity Planners

Shari J. Dermer, PhD

Manager, Educational Strategy and Content

Med-IQ

Baltimore, MD

Lisa R. Rinehart, MS, ELS

Director, Editorial Services

Med-IQ

Baltimore, MD

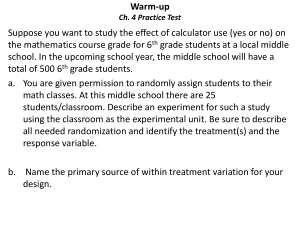

Trends in Incidence and Mortality for HCC

2001 to 2010

Trends in SEER Incidence Rates

Thyroid

Liver & Intrahepatic Bile Duct

Kidney & Renal Pelvis

Melanoma of the Skin

Pancreas

Corpus & Uterus, NOS

Testis

Myeloma

Oral Cavity & Pharynx

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Brain & Other Nervous System

All Sites Except Lung

Leukemia

All Cancer Sites

Urinary Bladder

Breast (Female)

Lung & Bronchus (Female)

Esophagus

Stomach

Cervix Uteri

Ovarya

Larynx

Lung & Bronchus (Male)

Prostate

Colon & Rectum

Trends in US Cancer Death Rates

-

6.3*

3.6*

2.4*

1.5*

0.9*

0.9*

0.6*

0.4

0.2

0.1

0

-0.3

-0.5*

-0.5*

-0.6*

-0.6*

-0.6

-0.7*

-0.9*

-1.1*

-1.7*

-1.7*

-2.1*

-2.2*

-2.3*

-2.6*

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0

2

4

6

8 10

Annual Percent Change, 2001 to 2010

*The APC is significantly different from zero (P < 0.05).

aOvary excludes borderline cases or histologies 8442,

8451, 8462, 8472, and 8473.

Liver & Intrahepatic Bile Duct

Thyroid

Pancreas

Melanoma of the Skin

Corpus & Uterus, NOS

Urinary Bladder

Testis

Brain & Other Nervous System

Esophagus

Lung & Bronchus (Female)

Kidney & Renal Pelvis

Leukemia

Oral Cavity & Pharynx

All Sites Except Lung

All Cancer Sites

Cervix Uteri

Myeloma

Ovary

Breast (Female)

Larynx

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Lung & Bronchus (Male)

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Stomach

Colon & Rectum

Prostate

2.4*

1.2*

0.5*

0.5*

0.5

0.1

-0.3

-0.5*

-0.6*

-0.9*

-1.0*

-1.0*

-1.3*

-1.4*

-1.5*

-1.5

-1.8*

-1.8*

-2.0*

-2.4*

-2.5*

-2.5*

-2.8*

-2.9*

-2.9*

-3.4*

-10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0

2

4

6

8 10

Annual Percent Change, 2001 to 2010

Howlader N, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. www.seer.gov.

Risk Factors for HCC

• Cirrhosis

– 87%-93% of patients with

HCC have cirrhosis at

autopsy and controlled

studies1,2

• Chronic liver disease

leading to cirrhosis3

– Hepatitis B

– Hepatitis C

• Male gender

• Increased age

• Diabetes

1. Tiribelli C, et al. Hepatology. 1989;10:998-1002;

2. Stroffiolini T, et al. J Hepatol.1998;29:944-52;

3. Fattovich G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-50.

Staging Classifications in HCC

Variables Measured

Staging

Classification Tumor Staging

CLIP

Tumor morphology (uninodular and extension ≤

50%, multinodular and extension ≤ 50%, massive

or extension > 50%), PVT

BCLC

Tumor size, number of nodules, PVT

GRETCH

PVT

US nomogram Resection margin status, tumor size > 5 cm,

satellite lesions, vascular invasion

Liver Function

Performance

Status

Year

Serum Tumor

Published

Markers

Child-Pugh

No

AFP

1998

CLIP investigators

Child-Pugh, bilirubin,

portal hypertension

PST

No

1999

Llovet et al.

Bilirubin, alkaline

phosphatase

Karnofsky

AFP

1999

Chevret et al.

No

Age, operative

blood loss

AFP

2008

Cho et al.

Ascites, albumin,

bilirubin

No

No

1985

Okuda et al.

Ascites, bilirubin,

alkaline phosphatase

Presence of

symptoms

AFP

2002

Leung et al.

Study

Okuda

Tumor size (</> 50% of liver)

CUPI

TNM fifth edition

JIS

Japanese TNM fourth edition

Child-Pugh

No

No

2003

Kudo et al.

bm-JIS

Japanese TNM fourth edition

Child-Pugh

No

AFP, AFP-L3,

DCP

2008

Kitai et al.

SLiDe

Stage and liver damage categories from the

Japanese TNM fourth edition

No

No

DCP

2004

Omagari et al.

Tokyo

Size and number of tumors

Albumin, bilirubin

No

No

2005

Tateishi et al.

BALAD

No

Albumin, bilirubin

No

AFP, AFP-L3,

DCP

2006

Toyoda et al.

ALCPS

Tumor size, PVT, lung measures

Ascites, Child-Pugh,

alkaline phosphatase,

bilirubin, urea

Abdominal pain,

weight loss

AFP

2008

Yau et al.

Reprinted with permission from Meier V, Ramadori G. Clinical staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2009;27:131-141.

BCLC Staging Classification

Stage 0

Stage A-C

PST 0, Child-Pugh A

Very early stage (0)

Single < 2 cm

Carcinoma in situ

Early stage (A)

Intermediate stage (B)

Single or 3 nodules Multinodular, PST 0

< 3 cm PST 0

Advanced stage (C)

Portal invasion,

N1, M1, PST 1-2

Terminal

stage (D)

3 nodules < 3 cm

Portal pressure/bilirubin

Increased

Resection

Okuda 3, PST > 2,

Child-Pugh C

Okuda 1-2, PST 0-2, Child-Pugh A-B

Single

Normal

Stage D

Associated

diseases

No

Liver transplantation

(CLT/LDLT)

Curative treatments

50%-70% at 5 years

Portal invasion,

N1, M1

Yes

PEI/RFA

Chemoembolism

Sorafenib

Randomized controlled trials

40%-50% at 3 years vs. 10% at 3

years

Symptomatic

treatment

Reprinted with permission from Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1907-1917.

RECIST Version 1.1

RECIST

CR

Disappearance of all target lesions

PR

30% decrease in the sum of the longest diameter of

target lesions

PD

20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of

target lesions

SD

Small changes that do not meet above criteria

Eisenhauer EA, et al. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-47.

SHARP: RECIST Response

Patients (%)

Sorafenib

Placebo

(n = 299)

(n = 303)

ORR*

CR

PR

SD

PD

Median duration of treatment, weeks

TTSP (as assessed by FHSI-8)

*Independent review by RECIST.

0

7 (2.3)

211 (71)

54 (18)

23

0

2 (0.7)

204 (67)

73 (24)

19

No significant differences

between treatment groups

(P = 0.77)

Llovet JM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-90.

Modified RECIST

RECIST

mRECIST

CR

Disappearance of all target lesions

Disappearance of any intratumoral arterial

enhancement in all target lesions

PR

At least a 30% decrease in the

sum of diameters of target lesions,

taking as reference the baseline

sum of the diameters of target

lesions

At least a 30% decrease in the sum of

diameters of viable (enhancement in the

arterial phase) target lesions, taking as

reference the baseline sum of the diameters

of target lesions

SD

Any cases that do not qualify for

either PR or PD

Any cases that do not qualify for either PR or

PD

PD

An increase of at least 20% in the

sum of the diameters of target

lesions, taking as reference the

smallest sum of diameters of

target lesions recorded since

treatment started

An increase of at least 20% in the sum of the

diameters of viable (enhancing) target lesions,

taking as reference the smallest sum of

diameters of viable (enhancing) target lesions

recorded since treatment started

Lencioni R, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-6.

Validation of mRECIST

1.0

Log rank P

CR vs. PR

< 0.001

PR vs. SD

0.002

SD vs. PD

0.023

0.8

OS

0.6

CR

0.4

PR

0.2

PD

SD

0.0

0

20

40

60

Time, months

80

100

Compared RECIST, WHO, EASL, and mRECIST

Reprinted with permission from Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim SO, et al. Which response criteria best

help predict survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolization?

A validation study of old and new models. Radiology. 2012;262(2):708-718.

Palliation of HCC: Sorafenib

Probability of Radiologic

Progression

Time to Radiologic Progression

1.00

Sorafenib

Placebo

0.75

0.50

0.25

P < 0.001

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Mos Since Randomization

Pts at Risk, n

Sorafenib

Placebo

Probability of Survival

• Before 2007, no therapy was of

benefit in advanced HCC

• SHARP trial: CTP A patients with

advanced HCC randomized to

sorafenib 400 BID vs. placebo

• Sorafenib delayed progression and

prolonged survival from 7.9 to 10.7

months

• Led to approval by the FDA in 2007

for palliation of advanced-stage HCC

• It remains the only approved

systemic therapy for HCC

299 267 155 101 91 65 37 23 18 10

303 275 142 78 62 41 21 11 10 3

4

1

2

1

0

0

OS

1.00

Sorafenib

Placebo

0.75

0.50

0.25

P < 0.001

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1314 1516 17

Pts at Risk, n

Sorafenib

Placebo

Mos Since Randomization

299 290 270 249 234 213 200 172 140 111 89 68 48 37 24

7

1

0

303 295 272 243 217 189 174 143 108 83 69 47 31 23 14

6

3

0

Reprinted with permission from Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378-390.

www.FDA.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm109030.htm.

Novel Therapeutics in Development

Target/Mechanism

Select Example(s)

Trial Design

Status

Anti-angiogenic mAb

Ramucirumab* vs. placebo (REACH)

AMG 386 + sorafenib

RP3

Phase 2

In follow up

In follow up

c-MET inhibition

Cabozantinib* vs. placebo

Tivantinib* vs. placebo (Metiv-HCC)

RP3

RP3, MET-high

In development

Enrolling, TPS 4159

Chemotherapy

combinations with

sorafenib

SECOX

Sorafenib ±GEMOX

Sorafenib ±DOX (CALGB 80802)

Phase 2

RP2

RP3

Abstract 4117

Abstract 4128

Enrolling

Immune modulation

Nivolumab* (anti-PD1)

Pexa-Vec* (poxvirus) vs. BSC

Tremelimumab* (anti-CTLA4)

Phase 1

RP2b, phase 2

Phase 2

Enrolling, TPS 3111

TPS 4161, Abstr. 4122

Sangro J Hepat. 2013

Metabolism/other

ADI-PEG20* vs. placebo

GC33* (anti-glypican 3) vs. placebo

RP3

RP2 (GPC-3

stratified)

Enrolling

Enrolling

mTOR pathway

Everolimus* (EVOLVE) vs. placebo

CC-223

RP3

Phase 1/2

In follow up

Enrolling

Multikinase/VEGFR

inhibition

Brivanib* vs. sorafenib

Brivanib vs. placebo

Linifanib* vs. sorafenib

Regorafenib* vs. placebo

Sunitinib* vs. sorafenib

Sorafenib ±erlotinib*

RP3

RP3

RP3

RP3

RP3

RP3

Johnson AASLD 2012

Llovet EASL 2012

Cainap GI ASCO 2013

Enrolling, TPS 4163

Cheng ASCO 2011

Zhu ESMO 2012

*Investigational

Reprinted with permission from Robin K. Kelley.

http://slides.asco.org/main/viewslide.asp?tpc=453&slide=97749&from=mtg&view=mtg.

Ramucirumab*

• VEGFR-2 and its ligands (including VEGF-A, -C, and -D) are

important mediators of angiogenesis, and angiogenesis is

integral to HCC carcinogenesis and pathogenesis

• Angiogenesis inhibition has been efficacious in both in vitro and

in vivo HCC models, and results of clinical studies also suggest

potential to inhibit disease growth

• Ramucirumab is a recombinant human IgG1 mAb that binds to

the extracellular domain of VEGFR-2 with high specificity and

affinity

• Ramucirumab was well tolerated in two phase 1 studies

involving patients with advanced refractory solid tumors; two

HCC patients (receiving doses of 10 mg/kg q2w) achieved

disease stabilization on-study for 9 and 14 months, respectively

*Investigational

Zhu AX, et al. ILCA 2010. Abstract O-033;

Zhu AX, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6614-23.

Phase 2 Ramucirumab* First-Line Study

in Unresectable HCC: OS

Survival Outcome

Median OS, mos

95% CI

1-year OS, %

95% CI

All Pts

(N = 42)

BCLC C

Child-Pugh A

(n = 31)

BCLC C

Child-Pugh B

(n = 11)

12.0

18.0

4.4

6.1-19.7

6.1-23.5

0.5-9.0

51.4

62.9

0

34.0-66.4

38.6-79.8

--

Treatment-related toxicities (≥ grade 3): hypertension (14%),

GI hemorrhage (7%), infusion reactions (7%), and fatigue

(5%); there was 1 death due to GI hemorrhage

*Investigational

Zhu AX, et al. ILCA 2010. Abstract O-033;

Zhu AX, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6614-23.

c-MET Inhibition in HCC

• Over-expression in

approximately 50% by IHC

(ARQ data)

• Retrospective series

Foundation Medicine: MET

amplification by NGS

28/2,223 (1.2%) samples

– 2/78 (2.5%) HCC

Santoro A, et al. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:55-63.

Hand-Foot Skin Reaction

• Hand-foot skin reaction is a group of symptoms affecting the hands

and/or feet1,2

– Varying degrees of severity that tend to decrease during the course of

therapy

• Side effects of antiangiogenic therapies usually occur during the first

few weeks of treatment3

• Patients may require2,3,4:

– Topical treatments

– Temporary suspension of treatment or dose reduction until the episode

resolves

– Permanent dose reduction (in severe or persistent cases)

Grade 1

Incidence: 8%*

*Incidence reported

from the SHARP

trial.[4]

Grade 2

Incidence: 6%*

Grade 3

Incidence: 8%*

1. Moldawer N, Figlin R. Oncol Nurs Forum.2008;4:699-708;

2. Wood LS. Commun Oncol. 2006;3:558-62;

3. Alexandrescu DT, et al. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:71-4;

4. Nexavar (sorafenib) PI. June 2013.

Photos courtesy of Elizabeth Manchen, RN, MS, OCN.

Management of Hand-Foot Skin Reaction

• Early intervention may prevent progression of

symptoms and avoid treatment interruption or

dose reduction1

• Patients are advised to1,2,3:

– Wear comfortable soft-soled footwear (eg, gel insoles)

– Apply hydrating cream, preferably containing urea

– Bathe regularly in lukewarm water containing Epsom

salts (magnesium sulphate)

• If possible, patients should consult a podiatrist

before starting treatment

1. Wood LS. Commun Oncol. 2006;3:558-62;

2. Anderson R, et al. Oncologist. 2009; 291-302;

3. Robert C, et al. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:491-500.

Diarrhea

• Loperamide is usually effective1,2,3

– If ineffective, consider using adjunctive codeine

– Ensure that patients are not dehydrated by monitoring urea

and electrolytes

– If severely dehydrated, patients may need to be admitted for

administration of IV fluids

• Patients experiencing treatment-induced diarrhea

should1,3:

– Monitor bowel habits and report any increase in activity above

normal

– Avoid spicy or fatty foods (plain, simple food is best)

– Avoid fruit and caffeine

– Maintain a good fluid intake to avoid dehydration

1. Wood LS. Commun Oncol. 2006;3:558-62.

2. Moldawer N, et al. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;4:699-708.

3. Benson AB, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2918-26.

Fatigue

• Not always attributable to drug therapy

• Usually managed by educating the patient

• Advise patients to:

– Stay as active as possible because that will

help them sleep better

– Maintain normal work and social schedules

– Take breaks as needed

– Tell their doctor or nurse if they cannot tolerate

activity or if their fatigue worsens

Wood LS. Commun Oncol. 2006;3:558-62.

Acknowledgement of Commercial Support

This activity is supported by educational grants from

Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Onyx

Pharmaceuticals, Celgene Corporation, Daiichi

Sankyo, Inc., and Lilly. For further information

concerning Lilly grant funding visit

www.lillygrantoffice.com

Copyright

© 2014 Med-IQ®. All rights reserved.