Planning Response to the Industrial City

advertisement

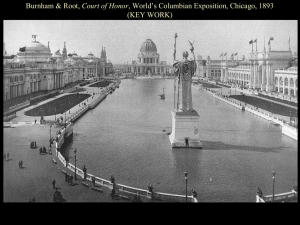

Geography of the Twin Cities Development Part 6: Planning Response to the Industrial City David A. Lanegran Geography Department Macalester College The World Fair grounds in Chicago in 1892 resulted in the development of a new attitude toward industrial cities. This fair was visited by more people that any event in the history of the world. The Chicago-based railroads brought people from all across the country to visit the grounds with its pavilion and the exciting Midway entertainment district. It was an opportunity to show off all sorts of new designs and styles. The Fair Committee gave the task of designing the fair to Daniel Burnham, a Chicago architect who was devoted to the City Beautiful Movement and the Beaux Arts Style. He was essentially a backward looking designer who used classical motives and French Second Empire styles. It is interesting to note that the Fair Committee did not select Louis Sullivan or one of the other modern architects working in the city at the time. The City Beautiful movement argued that cities did not have to be ugly to make money. The fairgrounds were filled with huge, white fanciful buildings, statues and public spaces that were fundamentally different from the gritty industrial cities of the time. The visitors were mesmerized. However, most builders of cities largely ignored the proponents of City Beautiful planning and instead built structures like the Federal Court Building in St. Paul (now Landmark Center) which was built out to the lot line in the Richardsonian Romanesque style. The leaders of Minneapolis were proponents of the City Beautiful movement and hired Burnham's firm to create a plan for the city which was released in 1917. This is the frontice piece. Burnham viewed Minneapolis as if it were a great metropolis, although he did not make detailed plans for the entire area until he clearly understood the connections among the various parts. He designed a metro area with Minneapolis as the core. He believed a city needed a grand entrance. For him that was the railroad depot. Therefore, he proposed that two new depots be built in the gateway district of the city which would provide a grand backdrop to a busy and attractive public space. He also wished to redesign the north façade of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and Fair Oaks Park. The chief design element is a grand boulevard coming from the center via the Art Institute onto Lake Harriet's northeast shore. This grand boulevard was justified as a solution to traffic problems encountered by suburban commuters and a way to provide housing for higher income people in the city. The boulevard would be a way to clear low quality housing in an early urban renewal program. In addition, it would provide a fire break in the event of a conflagration such as the ones that devastated Chicago and San Francisco. This is the Watergate where the boulevard terminated on the shore of Lake Harriet. It is the approximate location of the Rose Garden. Great effort was devoted to a plan for the redevelopment of the Mississippi. The Mansard roofs tell us that Burnham was using Paris as his model. He also wanted all the bridges over the river rebuilt to be more attractive. His idea of a riverfront park has been implemented in recent years. The plan also called for new crosscutting high traffic roads and a new community in Northeast Minneapolis. The wall to wall development of mansard roofed apartments he foresaw in the city contrasted sharply with the single family homes in the existing neighborhoods. He dismissed these structures as a great solution for small towns but not a good solution to the needs of the regional capital. Burnham's plan was never implemented, and the real estate companies built a city that would yield high profits, adopting the skyscraper design and technology developed in Chicago by Sullivan and others. Burnham hated skyscrapers; for him they were bad because they concentrated large numbers of people at one base location, which created traffic problems. Also, they cast shadows on neighboring blocks and the upper floors could not be reached by existing firefighting equipment. Furthermore, Burnham believed they were just monuments to man's vanity. When the Foshay Tower opened, John Philip Sousa lead a band around the block playing the Foshay Tower March. He was not paid for the music and so it was not published until the 1990s. Foshay did not live to enjoy his office tower, but it provides us with an excellent example of the changing nature of business in cities. The service sector expanded greatly in the 1920s and cities shifted away from a manufacturing base. The City of St. Paul hired the Burnham firm to do a plan in 1926. Burnham also tried to get the contract for the city hall and county court house. He designed this tremendous structure that was intended for the area where the Science Museum of Minnesota and the River Centre now stands. He was still interested in the railroad depot as the front door of cities, so he redesigned a few blocks near the St. Paul Union Depot, finished in 1917. The City rejected Burnham's design for the courthouse and instead built an outstanding example of a Streamline Modern skyscraper. However, the government's and court's function soon outgrew this building and have filled numerous other structures in the city center. Burnham may have known more about the future of the city and its employment structure that he is given credit for.