Institutional Design and Decision-Making Processes in

advertisement

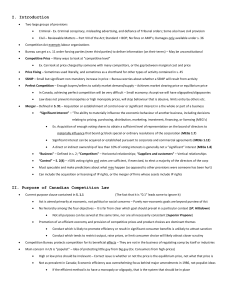

Institutional Design and DecisionMaking Processes in Canadian Competition Policy Edward Iacobucci and Michael Trebilcock University of Toronto Road Map • • • • 1) History and institutional design 2) Overview of the statute 3) Overview of institutional structure 4) Critical evaluation of institutional status quo: Due process norms (Friday) • 5)Critical evaluation of institutional status quo: Systemic performance (Saturday) 1) History and Institutional Design • Canada’s had a competition statute in place since 1889 • But very little activity until 1986 reform • Passivity of competition enforcement directly related to institutional design: because of concern about intruding on provincial constitutional domains, federal law was entirely criminal • High burden of proof; adjudication by (sceptical) nonspecialized criminal courts – E.g., merger that eliminated competition in a market permitted because Crown could not prove detriment to public interest History, cont. • Reform process began in late 1960s in face of considerable business opposition; reform not complete until passage of Competition Act in 1986 • 1986 statutory reform, and recent amendments in 2009, have shifted emphasis dramatically to civil from criminal law, with corresponding shift in institutions 2) Statutory Overview • Conduct either criminal or civilly reviewable • Following 2009 reforms, criminal offences restricted to hard core price-fixing and bidrigging – Per se offences, unlike predecessor provisions which required showing of “undue” lessening of competition – Defence available if price-fixing agreement “ancillary” to broader agreement; if so, then civilly reviewable practice Statutory Overview, cont. • Other anticompetitive conduct is civilly reviewable • Need to show a lessening of competition • RPM, refusal to deal, exclusive territories (“market restriction”), tying, exclusive dealing specifically enumerated in Act • Abuse of dominance provisions serve as catch-all • Merger provisions (including explicit efficiencies defence) Statutory Overview, cont. • Criminal offenders (price-fixers) subject to fines and imprisonment • Civilly reviewable anticompetitive conduct generally subject to injunctive cease-anddesist orders, though there is now scope for “administrative monetary penalties” for abuse of dominance • Narrow scope for private single damages actions if and only if criminal offence 3) Institutional Overview • Competition Bureau, headed by Competition Commissioner, investigates criminal matters, but the Department of Public Prosecutions prosecutes • Criminal matters heard in ordinary courts, with all due process afforded other criminal accused persons Institutional Overview, cont. • Bureau also investigates civil matters • Bureau frequently settles; may choose to register “consent agreement” with Competition Tribunal, which automatically imbues settlement agreement with authority of a court order • If no settlement, Tribunal will adjudicate (bifurcated agency model) • Tribunal comprises judicial and lay members, though in theory only judges make decisions of law • Appeals lie to Federal Court of Appeal, though deference is owed to Tribunal decisions Institutional Overview, cont. • While there is statutory authorization of expedited procedures, Tribunal procedures have historically resembled court hearings; some push to change in recent years • Very few matters are heard by Tribunal • Eg, five contested mergers since 1986; five contested abuse cases over same period; no substantive competition cases at all in 2008 Institutional Overview, cont. • Limited right for private parties to appear before Tribunal: with leave, not mergers or abuse; none successful to date in the result Bulk of decision-making rests with Bureau as a matter of fact: no private rights of action; very few cases before Tribunal 4) Critical Evaluation of Institutional Status Quo: Due Process Norms • Focus on civil matters; criminal engages broad panoply of ordinary protections for accused • Fresh perspective from series of interviews: all former Competition Commissioners (current refused to comment); Chair of Competition Tribunal; former economist at Tribunal and Bureau • Substantial consensus that institutional framework is not working well; much less consensus on reform • Central due process concern: accountability Due Process: Independence • Consensus is that bifurcated agency structure protects independence of decision-making well • Some minor concerns expressed about location of Bureau within Ministry of Industry: budget pressures potentially compromise independence? • No former Commissioner expressed concern about political influence over any given case, though some sympathetic to reform for systemic reasons Due Process: Accountability • Serious concerns expressed about accountability of Commissioner for case-by-case decision-making • Investigative powers are seen by some as having too few checks on Bureau’s power: eg s. 11 orders to produce documents are issued following ex parte hearing • More importantly, Tribunal is effectively a bit player • Vast majority of cases are resolved by settlement with no second look by the Tribunal: consent agreements, if entered into, are simply registered; very limited private rights of action Due Process, cont. • Some irony: one of the causes for concern about Bureau’s power is due process values at the Tribunal • Tribunal has historically granted court-like due process protections • Eg even interveners were given right to cross-examine witnesses; parties in Superior Propane merger case called almost 100 witnesses • In face of cost and delay of full court-like hearing before the Tribunal, parties generally prefer to resolve any questions with the Bureau in a settlement Due Process, cont. • Consensus on concern about accountability of de facto decision-making authority of Commissioner, but no such consensus on reform • Some fairly broad support for making Competition Commissioner a multi-member commission • But much less agreement on its authority: status quo? Fact-finder? Adjudicative authority, with right of appeal? Due Process, cont. • We are drawn to bringing greater adjudicative responsibility to Commissioners • This invites objections about degrading the impartiality of adjudication in any given case • But: – Structure adjudication procedures to protect against bias – De facto Bureau decides matters now; greater de jure integration of adjudication may engender greater independence if more cases are contested and there are rights of appeal – Independence of adjudication not a trump card (e.g., importance of expertise) 5) Critical Evaluation of Institutional Status Quo: Institutional Performance • Key due process concern, accountability in decision-making, also a problem of institutional performance • Focus now on other performance norms: expertise; predictability/transparency Expertise • Serious misgivings about expertise in Canadian competition institutions exist • Some misgivings about lack of economic sophistication at Bureau, but there is consensus that expertise at the Tribunal is inadequate • Two problems: members are not expert at time of their appointment; and do not develop expertise on the job Expertise, cont. • Judicial members of Tribunal are inexpert judges who may not ever have heard an antitrust case, yet they have sole decisionmaking authority over questions of law • Lay members have also not been expert in practice; instead it is seen by many as a political appointment (why this is such a plum escapes us...) Expertise, cont. • There is an important problem of selfreinforcement: because Tribunal is inexpert, parties are hesitant to appear before it, which hinders the development of expertise on the job • Lack of expertise may also contribute to the “fullcourt press” procedure, which in turn reduces case load: don’t have sufficient confidence in the issues to be more proactive in managing a case Predictability/Transparency • On its general approach to legal questions, Bureau is seen as relatively transparent – Eg Public draft and comment approach to enforcement guidelines • But on cases, much less transparency: matters get settled; if get anything, may be short press release, or cryptic consent agreement, but not much detail Predictability/Transparency, cont. • Lack of transparency on cases obviously impacts predictability: hard to gauge precise approach of Bureau in the past • Guidelines help, but these do not have force of law, nor do they even bind the Bureau one case to the next (notorious flip-flopping in Superior Propane case) Predictability/Transparency, cont. • Tribunal situation also contributes to unpredictability: there is very little case law • And self-reinforcing: with little case law (and inexpert adjudicators), parties do not want to take a chance before the Tribunal Reform • Substantial agreement on inadequate institutional performance; much less consensus on reform • We find greater integration of adjudicative functions within the Bureau attractive – Key: Greater expertise: adjudicators are immersed in competition policy – With more expert adjudicators, and streamlined procedures, hopefully there would be more adjudicated cases and greater transparency and predictability – Of course, concerns about adjudicative bias, but these (a) exist now; and (b) are not pivotal concerns on their own