soy report CArD 2014

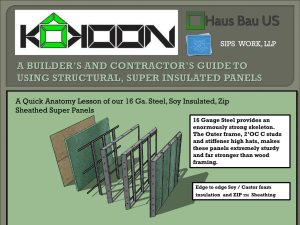

advertisement