Hydraulic Fracturing in the Marcellus Shale Formation

advertisement

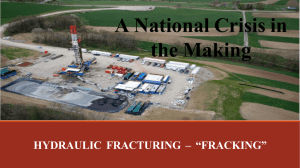

Hydraulic Fracturing in the Marcellus Shale Formation Why regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act is needed Marcellus Shale Formation • Massive rock formation of gas bearing shale located in Pennsylvania, southern New York, eastern Ohio, and northern West Virginia • Estimated to provide enough shale gas to power the United States for more than two decades • Largely untapped until technology called hydraulic fracturing developed Hydraulic Fracturing • Also known as “fracking” • Machines inject highly pressurized water and mostly toxic chemicals into shale gas formations about a mile underground • Cracks are created in shale that open small pores where the gas is trapped • The freed gas rises to surface and is piped away • Extraction process not without danger and environmental consequences. • Currently is exempted from regulation under Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) • Enacted by Congress in 1974 • Authorized states to create specific regulations to protect their underground drinking water sources • Any state wanting their own regulatory regime must incorporate a plan to regulate industrial underground injection control (UIC) programs • Most industrial extraction processes involve injection of “propping” agents use to pry open gaps in underground reservoirs • Propping agents under UIC programs include sand, water, nitrogen, and diesel fuel • EPA granted statutory exemption for hydraulic fracturing Horizontal Drilling and Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals Used in Fracking • Proprietary mix of up to 14 undisclosed chemicals • Friction reducers to help mixture flow • Rust prevention compounds • Microorganism killing bactericides • Methane and petroleum distillate blend Points of Potential Contamination • Flow back fluid can leak at well head • Enormous pressures used in extraction can cause malfunctions at the surface • Pipe bursting underground • Well crossing pockets of methane allowing gas to rise up in borehole to groundwater • Fluids are subject to spillage during transport • Leaks from poorly built or unlined holding ponds Negative Impacts • Fracking discharge is accused of negatively in water quality in Virginia, Alabama, Wyoming, Montana, Colorado and Pennsylvania • Complaints from residents living near fracturing fields include greasy films in water, pungent odors, increased salinity, and even a rise in certain types of cancer • Water flushing black or orange • Water turning bubbly • Elevated levels of metal and toluene (benzene derivative) Regulation History • Legal battle to regulate hydraulic fracturing began in 1997 over unregulated wells in Alabama and groundwater contamination • 11th Circuit Court held that hydraulic fracturing fit within definition of “underground injection which was already regulated through UIC programs • EPA responded by conducting study from 2000-2004 that found injection of certain chemicals posed little or no threat to underground sources of drinking water • In 2005, Congress exempted oil and gas industry from hydraulic fracking regulations • Exemption know as Halliburton Loophole Steps Toward Regulation • New hydraulic fracturing study now underway by EPA • EPA has sent voluntary information requests to nine leading national fracturing service providers requesting list of chemicals used • Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals (FRAC) Act introduced in 2009 aimed at closing Halliburton Loophole and restoring EPA’s power to regulate • Kerry-Lieberman American Power Act introduced in May 2010 calls for disclosure of chemicals used in fracking mix • Local governments have written resolutions and letters supporting regulations under SDWA Policy Formation • Options include regulating under section 1425 of SDWA or require oil industry to use biodegradable fracturing fluids instead of toxic chemicals • Section 1425 allows states to demonstrate their existing UIC programs are effective in preventing contamination of USDWs • Regulate under Section I425 by declaring hydraulic fracturing wells to be Class II wells