Phytoremediation of Pharmaceuticals, Hormones, and other Organic

advertisement

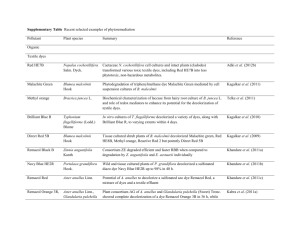

Phytoremediation of “Contaminants of Emerging Concern” Corbett Landes, Kim Fewless, and Meg Hollowed November 11, 2010 BZ 572 Prevalence in the Environment Found in 80% of U.S. streams Largely either very hydrophilic or hydrophobic compounds Most frequently detected: steroids non-prescription drugs insect repellent detergent metabolites disinfectants Highest concentrations: steroids non-prescription drugs detergent metabolites plasticizers disinfectants antibiotics Why do we care about pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants? Low concentrations, but: many compounds aren’t regulated fate and transport of metabolites aren’t well understood potential for interactive effects Where do they come from? wastewater treatment plant effluent agricultural operations/runoff Organizations currently engaged in research: EPA, WHO, USGS, etc. Potential applications for phytoremediation Municipal wastewater treatment Feedlot or dairy farm waste stream treatment Agricultural runoff abatement Antibiotics Agricultural Sources: Growth promotion and disease prevention Released to the environment through: feedlot runoff streams leaks runoff from manure-applied agriculture Consequences antibiotic resistant microorganisms Antibiotics Cont: CSU study Aquatic plants Parrot feather (M.aquaticum) and water lettuce (P. stratiotes) Hairy root cultures of sunflower (H.annuus) Antibiotics: tetracycline and oxytetracycline Mechanism: degradation by root-secreted enzymes Antibiotics, Cont: Conversion of former shrimp aquaculture facilities contaminated with antibiotics and with elevated salinity Antibiotics: oxytetracycline, norfloxacin Tested soybean for uptake/degradation, affect of salinity and antibiotics on soybean plants Translocation did not occur Antibiotic accumulation only in root tissue Kow=-0.9 and -1.8 Pharmaceuticals Acetaminophen Can be moved into plants Causes irrevocable damage in most plants tested Most success found in Lupinus albus Ibuprofen Phragmites australis Hormones/Endocrine Disruptors Removal of phenolic endocrine disruptors by Portulaca oleracea Specifically bisphenol A Could potentially be used as a cash crop Steroids in Swine Wastewater Anaerobic lagoon and constructed wetlands Shown to decrease estrogen activity by 83-93% Estrone was the most persistent compound Also decreases nutrient content Constructed Wetlands Literature Treatment Compounds Results Dordio (2010) Microcosm CW Ibuprofen, carbamazepine, clofibric acid Seasonal variability, adsorption to clay, plants Song (2009) Variation of wetland depth Estrone, 17-estradiol, 17α-ethinylestradiol Shallow depth, aerobic, high root density Conkle (2010) Constructed Wetland Ciprofloxacin, ofloxin, norfloxin (fluoroquin) Sorption, drugs of same family compete for sorption sites Matmoros (2007) VFCW/HFCW/sand filter/WWTP Ibuprofen, carbamazepine, caffeine (13) Biodegradation and sorption – effectiveness: VF>SF/WWTP>HF Hijosa-Valsero (2010a) Pond, SF & SSF CW vs. WWTP Ibuprofen, carbamazepine, caffeine (10) aerobic, microbiological Hijosa-Valsero (2010b) Mesocosm CW (3) Ibuprofen, carbamazepine, caffeine (10) Correlated with temp and redox potential microbiological Typha angustifolia Phragmites australis Aquatic Plants Literature Treatment Compounds Results Reinhold (2010) Duckweed Atrazine, ibuprofen, 2,4D, triclosan (7) Enhanced microbial degradation, sorption, uptake Shi (2010) Duckweed v. Algae Estrone, 17-estradiol, 17α-ethinylestradiol Both algae and duckweed accelerated degradation through sorption and microbial degradation Summary: constructed wetlands Wetlands and other aquatic phytoremediation of PPCPs works as well as traditional treatment Application in developing countries May be more cost effective Variation in degradation requirements Anaerobic/aerobic Temperature Photolysis Sorption/degradation Use patterns (Macleod, 2010) CONCLUSIONS Some success has been achieved with specific plants/compounds Must consider risks: Invasive species Metabolites Ability to remediate a mixture of compounds Research is still being conducted to understand the fate and transport of CECs/PPCPs At this time, no single plant or constructed wetland set-up can remove all PPCPs in wastewater treatment plant effluent References (1) Bartha et al. (2010). Effects of acetominophen in Brassica juncea L. Czern: investigation of uptake, translocation, detoxification, and the induced defense pathways. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res., 17, 1553-1562. Boonsaner, M. and Hawker, D.W. (2010). Accumulation of oxytetracycline and norfloxacin from saline soil by soybeans. Sci of the Total Env, 408, 1731-1737. Conkle JL et al. (2010) Competitive sorption and desorption behavior for three fluoroquinolone antibiotics in a wastewater treatment wetland soil. Chemosphere 80, 13531359. Dordio A et al. (2010) Removal of pharmaceuticals in microcosm constructed wetlands using Typha spp. and LECA. BioresourceTechnology 101, 886-892. Hijosa-Valsero M et al. (2010a) Assessment of full-scale natural systems for the removal of PPCPs from wastewater in small communites. Water Research 44, 1429-1439. Hijosa-Valsero M et al. (2010b) Comprehensive assessment of the design configuration of constructed wetlands for the removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products from urban wastewaters. Water Research 44, 3669-3678. Gujarathi et al. (2005). Phytoremediation potential of M.aquaticum and P.stratiotes to modify antibiotic growth promoters, tetracycline and oxytetracycline, in aqueous wastewater systems. Int. Journal of Phytoremediation, 7, 99-112. References (2) Gujarthi et al. (2005). Hairy roots of H.annuus: a model system to study the phytoremediation of tetracycline and oxytetracycline. Biotech. Prog. 21, 775780. Imai et al. (2007). Removal of phenolic endocrine disruptors by Portulaca oleracea. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengr., 103(5), 420-426. Kolpin et al. (2002). Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in U.S. streams, 1999-2000: a national reconaissance. Env. Sci. & Tech., 36, 1202-1211. Kotyza et al. (2010). Phytoremediation of pharmaceuticals- preliminary study. Int. Journal of Phytoremediation, 12, 306-316. MacLeod, SL et al. (2010) Loadings, trends, comparisons, and fate of achiral and chiral pharmaceuticals in wastewaters from urban tertiary and rural aerated lagoon treatments. Water research 44, 533-544. Reinhold D et al. (2010) Assessment of plant-driven removal of emerging organic pollutants by duckweed. Chemosphere 80, 687-692. References (3) Matamoros et al. (2007). Removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from urban wastewater in a pilot vertical flow constructed wetland and a sand filter. Env. Sci. & Tech., 41, 8171-8177. Pedersen et al. (2005). Human pharmaceutical, hormones, and personal care product ingredients in runoff from agricultural fields irrigated with treated wastewater. J. Agr. Food. Chem., 53, 1625-1632. Schroder et al. (2007). Using phytoremediation technologies to upgrade wastewater treatment in Europe. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res., 14 (7), 490-497. Shappell et. al. (2007). Estrogenic activity and steroid hormones in swine wastewater through a lagoon constructed-wetland system. Env. Sci. and Tech., 41, 444-450. Shi W. et al. (2010) Removal of estrone, 17α-ethinylestradiol, and 17 –estradiol in algae and duckweed-based wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 17, 824-833. Song HL et al. (2009) Estrogen removal from treated municipal effluent in smallscale constructed wetland with different depth. Bioresource Technology 100, 29452951. Topp et al. (2008). Runoff of pharmaceuticals and personal care products following application of biosolids to an agricultural field. Sci. of the Total Env., 396, 52-59.