Shale Gas and Oil in the Spotlight: 2011 Litigation, Legislation, and

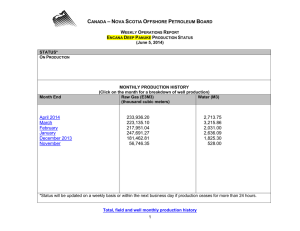

advertisement

Shale Gas and Oil in the Spotlight: 2011 Litigation, Legislation, and Regulation Professor Hannah Wiseman Key points • Development of oil and gas from shales and tights sands is rapidly expanding, largely as a result of “slickwater” hydraulic fracturing (2-5 million gallons of water per well + 0.5% chemicals by weight). • Unconventional development in shales and tight sands involves many stages, not just fracing. • Potential environmental effects: largely arise because fracing enables the drilling of thousands of new wells, but also from new activities introduced by fracing: chemical transportation and disposal of new wastes, for example. • The states have primary responsibility for controlling the environmental effects of oil and gas development, and state regulations vary substantially. • Law suits, state legislation, modified state regulations, and federal regulation of fracing are slowly emerging. The rapid expansion of shale and tight sands development enabled by fracing http://www.eia.gov/energy_in_brief/images/charts/large-ppt24.jpg The numbers • The Energy Information Administration believes that the United States has 2,543 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas, 862 Tcf of which are trapped within shales. • This quantity of gas at 2010 U.S. consumption rates could supply more than 100 years of gas. • Don’t forget oil: fracturing is also ramping up production of oils from shales, particularly in the Bakken Shale (North Dakota, Montana). • About 90% of new gas wells are hydraulically fractured. The many stages of shale or tight sands development • • • • • • • • • • Conduct seismic testing Construct an access road and well pad Drill, case, and cement a well Store drilling wastes on site (fluids, drill cuttings in open surface pits or tanks) Dispose of drilling wastes Transport water and chemicals to the site Perforate and fracture the well Capture produced water and flowback water Dispose of flowback Enter the production phase and restore the site Conducting seismic testing • Identify best areas for production through seismic testing (use “thumper” truck or blast a shot hole to create underground vibrations, record and chart data). http://www.netl.doe.gov/technologies/oilgas/petroleum/projects/ep/images/ThumperTruck2.jpg Potential effects • Potential damage to homes, structures if not conducted properly • Erosion and sedimentation, soil compaction from trucks • Unplugged shot holes as safety hazard • Water contamination from stream crossings , blasting in or near wetlands http://www.fe.doe.gov/images/programs/sequestra tion/thumper_trucks.jpg Seismic testing regulation Arkansas Required 200 ft. distance between shot hole and building or water well Oklahoma Texas New York Pennsylvania 200 ft. (500 ft. for Superfund site) -- 250 ft. (roads No minimum and trails in distance; state parks) provides maximum peak particle velocity at closest building Arkansas, Colorado, Louisiana, Montana, North Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming require that shot holes be plugged. Maryland allows its DEP to deny a seismic permit if testing “posses a substantial risk of causing environmental damage that cannot be mitigated by the applicant.” Constructing a well pad and access road • Access road 0.1-2.75 acres • Well pad 2.2-5.7 acres (average 3.5) http://208.88.130.69/uploadedimages/Issues/Articles/Apr-2011/0411-Shale-MarcellusPennsylvania.jpg Potential effects • Erosion and sedimentation, pollution of nearby waters – Michigan May 2011: access road “badly eroded,” violation noted, no enforcement – Pennsylvania “failure to minimize erosion” noted at more than 30 Marcellus sites in 2011 • Onsite spills from equipment (diesel, etc.) • Habitat fragmentation, other wildlife impacts http://aarconinc.com/images/thumbs/marcellusshale.jpg Federal law • Construction general permit required for oneacre sites and greater (stormwater) – typically state-administered • Consultation with Fish and Wildlife Service and potential incidental take permit necessary if endangered or threatened species are on or near the site. Minimum distance between well pad, well, or pits and domestic and natural resources Arkansas Oklahoma Texas New York Pennsylvania Dwellings and other structures 200 ft. -habitable, 300 ft. other structures 200 ft. 100 ft. 200 ft. Private water wells -- 300 ft. (land application of wastes) -- 500 ft. 200 ft. Streams Closed-loop system if w/in 100 ft. of stream and use oilbased drilling fluids 100 ft. (between land application and perennial stream); 50 ft. (intermittent stream) -- 150 ft. (well); 150 ft. 500 ft. (fueling tanks) DRBC: 500 ft. New York: proposed additional protections during construction phase • Special general construction permit for oil and gas drilling site construction • State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit for stormwater discharges within 500 feet of principal aquifers (Preliminary Revised Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement September 2011) Drilling, casing, and cementing a well: procedure and potential effects • Shale and tight sands wells often are very deep (thousands of feet) and are often, but not always, drilled horizontally. • Operators must case (“line”) a drilled well with steel tubing to keep the wellbore from caving in, to allow oil or gas to flow up through the well, and to prevent substances in the well, such as oil and gas, from “communicating” with (mixing with) underground resources, such as fresh water. • If pressure builds up in the well during drilling, the well can “blow out,” thus compromising the casing and possibly causing pollution. Potential effects during drilling, casing, and cementing, continued • Fuel pumps may malfunction, causing spills. • Drilling mud and fluids may spill. • Improper casing may cause natural gas to contaminate drinking water. – New Mexico August 2010: fuel pump split, spilling 1,000 gallons of diesel; 100 gallons recovered. Violation noted, no enforcement. – Louisiana June 2009: casing valve at well head was open, causing drilling mud to drip out. Administrative order and settlement. November 2009, spill of oil-based drilling mud migrated to natural drainage. Admin. order. – Pennsylvania July 2009 : due to improper casing, methane contaminated stream tributaries and water wells . $44,125 settlement. May 2011: Chesapeake fined $900,000 for methane contamination of water wells. Note that some methane migrates naturally to water wells (and not as a result of gas well drilling) No federal regulation of drilling, casing, cementing except for federal leases • States are responsible for writing and enforcing the drilling, casing, and cementing of oil and gas wells. • The federal government may add drilling, casing, and cementing protections for leases on federal lands, however. The BLM plans to finalize best management practices, for example, which will address well integrity. (Initial DOI forum in DC in November 2010, regional BLM forums held in 2011.) State casing and cementing requirements Arkansas Oklahoma Texas New York Pennsylvania Depth of 100 ft. surface casing below lowest fresh groundwat er 50 ft. or 90 ft. below surface, whichever deeper Below all known or reasonably estimated groundwater 75 ft. or into bedrock, whichever deeper; 100 ft. in primary and principal aquifers 50 ft. or into consolidated bedrock, whichever deeper Cementing Correction of surface of cement casing deficiencies required before fracturing Cement must set at least 8 hrs. before drilling. Allow surface casing to set until compressive strength 500 psi in critical cement zone No casing disturbance until achieves compressive strength of 500 psi Relies on American Petroleum Institute cementing specifications Ohio has one of the deepest surface casing requirements (500 feet below lowest freshwater). Storing drilling wastes on site: potential effects • Stored in pits or steel tanks. Open pits can attract birds. • Improperly constructed pits can leak, either by overflowing or allowing leakage through a torn liner. • Fluids can spill during transfer from well to storage pit. http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/pressrel/oilBirds.JPG Examples of surface spills during drilling fluid transfer or waste storage or transfer • Pennsylvania February 2011: $188,000 penalty for failure to contain materials in tanks. • Louisiana March 2009: produced water overflowed from tanks and entered swampy area. Administrative order. http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/oilandgas/images/rig_reserve_p it.jpg Federal regulation • Most oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) wastes, including some wastes containing hazardous substances, are exempted from hazardous waste regulation under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act; states regulate handling, storage, and disposal. • Non-exempt hazardous wastes must be handled and disposed of under RCRA. http://www.shippinglabels.com/img/lg/D/Vinyl-Hazardous-Waste-Label-D1745.gif State regulation of drilling waste storage Arkansas Oklahoma Spill/leak prevention Tanks with produced fluids must be surrounded by containment structures -- Reserve pit or drilling pit liner and freeboard 20-mil synthetic, 2 ft. Geomembrane liner if near water, 2 ft. Texas -- 2 ft. only for brine evaporation pits New York Pennsylvania Troughs, drip pads, pans beneath tank fill ports; secondary containment for large tanks and small tanks w/in 500 ft. of water resources Preparedness, Prevention, Contingency Plan for spill prevention 30-mil synthetic, 2 ft. Synthetic, permeability of no greater than 1 x 10-7 cm/sec, 2 ft. Disposing of drilling wastes: potential effects • Improperly-cased underground injection control wells may leak and contaminate underground drinking water sources. – Texas Heritage Consolidated bankruptcy case November 2010: UIC well (with wastes from Crittendon field) leaked into Midland’s Cenozoic Pecos Alluvium Aquifer, contaminating the city’s drinking water supply. Operator filed for bankruptcy. Disposing of drilling wastes: potential effects, continued • Salty produced water improperly applied to roads and other surfaces could pollute surface waters and soils – New Mexico June 2002: $7,500 penalty for application of produced water to a road; July 2004 violation noted when 480 barrels of produced water were applied to a road without a permit. • Improperly buried drill cuttings—particularly if they were drilled using salty or oil-based drilling fluids—could pollute surface waters or soils. Disposing of drilling waste: potential effects, continued UIC wells drilled in or near fault zones can cause localized, mostly small earthquakes. Oklahoma Geological Survey (Aug. 2011) points to several cases, concluding: "Cases of clear anthropogenically-triggered seismicity from fluid injection are well documented with correlations between the number of earthquakes in an area and injection, specifically injection pressures, with earthquakes occurring very close to the well.” More research needed. http://www.ogs.ou.edu/pubsscanned/openfile/OF1_2011.pdf Federal regulation • States regulate most disposal, which occurs on road surfaces, drill sites, in centralized E&P facilities, through wastewater treatment plants, or in underground injection control wells. • The EPA regulates underground injection control wells under the Safe Drinking Water Act; most states have primacy and are responsible for issuing and enforcing UIC permits under the SDWA. State regulation of drilling waste disposal Arkansas Oklahoma Texas New York Pennsylvania Pit on site or land application Drill cuttings from oilbased drilling Class I Commercial landfill or pit or land other ADEQ- application approved methods Burial on site Solid waste disposal facility Waterbased drilling fluids Landapplied, sent down well bore, dried and buried on site, UIC well, etc. Landfarmin g if low chloride, burial of dewatered high chloride (Likely Discharge to landfill land only with disposal permit required; not wholly clear from SGEIS.) Produced water Same as Discharge to UIC wells water-based land with drilling restrictions fluids Commercial pit, commercial soil farming, land application Road spreading after NORM analysis, POTW POTW after treatment Fracturing a well: potential effects • Chemicals may spill during transport. – 2005-2009, more than 780 gallons of more than 2,500 different types of hydraulic fracturing products were used in wells around the country. Most widely-used chemical was methanol. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce, Minority Staff Report April 2011. • The well may blow out during fracturing. – In April 2011, a well in Pennsylvania blew out during the fracturing process, causing several thousand gallons of fracturing fluids to enter a nearby creek. In May 2011, Maryland’s attorney general threatened to sue. Fracturing a well: potential effects, continued • Fracturing fluids may spill on site when being transferred or stored – New Mexico March 2009: 800 barrels of fracturing fluid spilled out of tanks when valve was opened – New Mexico May 2009: 15 barrels of fracturing fluid spilled when operator mistakenly placed fluid in tank that had a leak State regulation of fracturing Chemical disclosure Arkansas Oklahoma Texas New York Pennsylvania All chemical additives, including rate and concentration (agency) Volumes of frac fluid and proppant used (agency) All chemical ingredients (public) Every additive product (will be public) Chemicals or additives utilized (agency) Arkansas, Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota have recently updated their oil and gas regulations to specifically govern the practice of fracturing—requiring improved casing and blowout prevention, for example. Oklahoma regulations point oil and gas operators to the portions of the regulations that apply to fracturing. Several states, such as Texas and West Virginia, require reporting of water quantities used for fracturing. Disposing of fracturing wastes: potential effects • Both produced water (which comes up naturally from the formation during the drilling stage) and flowback water can contain low levels of naturally-occurring radioactive materials (NORM). • Flowback water contains low concentrations of fracturing chemicals. • Wastewater treatment plants may be inadequately equipped to treat large quantities of flowback water. Federal regulation • The EPA sent a letter to the Pennsylvania DEP in March 2011 expressing concerns that wastewaters from Marcellus drilling and fracturing weren’t being adequately treated by wastewater treatment plants and could be discharging low levels of radioactive wastes into rivers. • The Pennsylvania DEP responded in April 2011, indicating that it had tested the water quality in the rivers below the discharge points and have found no violations. Federal regulation of fracturing waste disposal, continued • Request of Pa. DEP and Governor Corbett: After May 19, 2011, stop sending fracturing wastewater to “grandfathered” POTWs in Pennsylvania. • In May 2011, the EPA sent a Section 308 Clean Water Act request to the six largest energy companies operating in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus, asking for detailed information on how they have been disposing of their wastewater. The EPA also sent a follow-up letter to the DEP, continuing to express concerns about Marcellus wastewater treatment. • In October 2011, the EPA promised to regulate wastewater from fracturing in shales under the Clean Water Act by 2014. Lawsuits RE: fracturing waste disposal • July 2011, Pennsylvania environmental groups (represented by Pittsburgh Law environmental clinic) sued a municipal wastewater treatment plant, alleging Clean Water Act violations for accepting Marcellus drilling and fracturing waste and inadequately treating the 80,000100,000 gallons/day of wastewater that it discharges in the Monongahela River. State regulation of fracturing waste disposal Flowback Arkansas Oklahoma Texas New York Only specifies that no permanent disposal in pits is permitted. Recycling, burial, noncommer cial pits, injection (but see statement by Commission er Jeff Cloud: only recycling or injection) Likely only POTWs UIC wells or recycling Pennsylvania Previously POTWs, now recycling, outof-state POTWS Overall trends • Many states moving toward disclosure (see also FracFocus). • Several states initiating lawsuits (New York, potentially Maryland). • EPA regulating wastewater and VOC air emissions. • Several states are updating regulations to recognize fracturing.