From research to clinical work

in pregnancy

Massimo Ammaniti

(Sapienza University of Rome)

massimo.ammaniti@uniroma1.it

For a woman and for the couple pregnancy is an extremely

important transition phase, during which one prepares to

become a parent and to take care of a child who will be

immature and dependant for all his first year of life. Research

and clinical contributions have lent specific attention to the

construction of the maternal identity, defined by Stern (1995)

maternal constellation, and to the development of maternal

capabilities during pregnancy, which are indicative and

foretelling of the mother-child relationship after birth, even in

at-risk situations.

The psychology and the psychopathology of pregnancy have

been studied using research tools that have addressed

different areas. In this paper we will take into consideration a

few of the more relevant research areas for this phase:

1) The psychological dynamics connected to the

attainment of the maternal identity, analysed through the

mental representations of pregnant women;

2) The formation process of the mother’s attachment to the

child during pregnancy, which prepares the stabilization of

this attachment after birth;

3) Mental states specific to pregnancy, such as the primary

maternal preoccupation (Winnicott, 1956).

The assessment of prenatal parenting has been done through

research instruments with different purposes: semi-structured

clinical interviews, self-report-questionnaires and scales.

1) Semi-structured clinical interviews that investigate the

pregnant woman’s mental representations, focusing

attention to the woman’s past experiences, to how she

copes with pregnancy and maternity and to how she

progressively creates the image of the foetus and of the

future child. To study the mental representations the woman

has of herself as a mother and of the child in a more

systematic way, attention is put on the structure of the

narration the woman does during the interview. The

interview is very susceptible an instrument for exploring

parenting mental representations when they are still not

defined and stabilized.

Among prenatal interviews, the IRMAG-R (Interview for

Maternal Representations during Pregnancy- Revised

Version, Ammaniti et al., 1992-2008) must be noted; this is

a semi-structured interview made of 41 questions which

bring women to tell their experience of pregnancy and of

becoming mothers: their stories are not evaluated by their

content, but on the basis of their narrative structure. The

Interview is performed between the 6th and the 8th month

of pregnancy and is audiotaped and transcribed. The

average length of the Interview is approximately 45 minutes.

The Interview explores the following areas:

I How the mother organizes and communicates her

experience through a narrative structure

II The desire of maternity within the personal and

marital history

III Partner’s and family’s reactions to the news of the

pregnancy

IV Emotions and changes in personal life, in

relationship with the husband/partner and between

the two families occurred during pregnancy

V Impressions, negative and positive emotions,

maternal and paternal representations: space for

internal baby

VI Temporal perspective: expectations for the future

VII Historical perspective with respect to the mother’s

past

The narrative structure of the interview is coded considering

the mother's representation of herself as a mother and her

representation of the child on the basis of seven parameters :

Richness of perception

It refers to the woman’s acknowledgement of herself as a

mother and of the child: this parameter evaluates the way the

episodes, the feelings and the emotions of the woman herself,

of her partner and of the future baby are told.

Openness to change

This parameter evaluates the mother’s flexibility towards

those physical and psychological transformations which are

specific to the experience she is living, referred to herself and

to the future baby. It evaluates the capability of recognising

these physical and psychological changes which involve

herself, her emotional, sexual and relational life as being part

of the process. It evaluates the capability to modify the

representation of the baby as the pregnancy goes along.

Intensity of the involvement

This scale is used to measure the breadth of the woman’s

psychological involvement in confronting experiences

connected to the pregnancy, to the child and to her relation

with the child; this can be found in the description of the

emotional echoes caused by the event as well as in the

woman’s participation to the interview.

Coherence

It measures the story’s coherence, by which the woman,

through a well organised and logical narrative flux gives a

comprehensible picture of herself as a mother, of the child

and of her relation with the child. Coherence is found in the

plausibility of the story told and in the capability to provide

evidence and episodes which sustain her considerations

and her evaluations.

Differentiation

It evaluates the level of the mother’s acknowledgement of

her personal boundaries, of her stable mental and physical

characteristics, of her specific needs and wishes,

differentiated from those of her partner and of her parent

figures. It evaluates the degree to which the mother is

conscious that the child has his own mental and physical

characteristics, with specific boundaries and specific needs.

Social dependence

It evaluates the degree of influence and dependence, to the

limit of subordination, of the woman’s representation of

herself as a mother and of the child from the opinions,

judgements and messages coming from the partner, the

family, friends, the social context, mass media, social and

medical institutions.

It measures the degree of conformism towards others, which can

in extreme cases cause a flatness of representation and a lack of

personal elaboration.

Predominance of fantasies

It is used to measure the emerging of fantasies regarding the

pregnancy, her future motherhood and the representation of the

child, intended as all those images, metaphors, analogies, openeye and night dreams, expectations, fears and wishes which

characterise the way a woman imagines the pregnancy

experience and the representation of herself as a mother and of

the child. The fantasies can refer to the pregnancy itself, to the

woman’s body, to delivery, to rearing, to the integrity and physical

health of the baby, its physical and character qualities, to the

mother’s role; these can all have a more or less realistic quality.

It is not only the number of fantasies which must be considered

in assigning the score but their importance and their impact on

the representation of the mother and the child.

These seven parameters all refer to the woman’s representation

of herself as a mother and to her representation of the child and

are codified in scales with a five-point range (from 1 to 5). The

assignment of the final score individuates three different styles

of maternal representation:

Integrated/Balanced

The integrated/balanced maternal representations are coherent

narrations, in which the description of the experience the woman

is living is rich in episodes, moods, and has an intense

emotional involvement in an atmosphere of flexibility and

openness towards the physical, psychological and emotional

transformations the mother is confronting. The relationship with

the child is already present during the pregnancy, and the child

is considered as a person with his own motives and moods.

Integrated/Balanced Mothers

Martina’s story is a perfect example of an Integrated Mother

model . In her answers, we feel the importance she gives to

her pregnancy on which she has concentrated all her forces.

A great capability of recognising her mental states as well as

her husband’s emerges from her words, as if she is used to

examining herself and the people who surround her.

Q – Would you tell me about your pregnancy?

A – This was a desired pregnancy, completely, even

because I’m more than 30 years old. I was once married,

then separated and now I live with this new man who gives

me great tranquillity. I have always wanted a child, so I

thought I had to have it now or decide I’d have a life without

children. So I did all the tests, a year before, I got prepared;

it definitely was a planned pregnancy. When I became

pregnant, I had just switched to a new job, since I was

planning to have a child I had switched from a full-time to a

part-time job. I have many interests, I do artistic gymnastics

and many other things; I don’t believe you have to quit

everything when you have a baby. Of course you will be

dedicating most of your time to the baby, but you have to

keep doing your own things.

Q – How did you face this pregnancy?

A – I had some problems, from a physical point of view.

Psychologically I faced it very well. Of course you are a bit

shocked, I think that happens to everyone because there’s

something new, something you don’t quite understand,

especially when you have your first ultrasonography, when

it’s still tiny, you see this little spider. And then this child is

growing inside of you. It kicks you, and you feel something

weird and think “Oh God, there’s a baby growing inside of

me”. I know it’s not really strange but it just surprises you.

I actually accepted it from the start; I wanted a child so

much; of course it’s also important that the man I live with

now gives me such tranquillity.

Q – Would you tell me how you felt when you first found out

you were pregnant?

A – When I first found out, because of the practical problems

with my job I wasn’t actually sure if I should be happy or not.

Then I thought that everything could be arranged, because

even when confronting problems of schedules, of work, when

you know you’re going to have a baby it all becomes relative

before the baby.

At first you’re a bit surprised, even because they tell you you’re

pregnant but you can’t feel it yet. You feel as usual, normal, at

least until you start growing a belly.

Q – Who else did you tell?

A – My mother, my father, my cousin

Q – All the same day?

A – Yes, the same day. I called my mother that evening. I

wasn’t sure if I should tell her immediately, or how to tell her, if

in person. Then I just called.

Q – When did you notice the first changes in your body?

A – Everybody asks that. In the first few months, only around

the fourth month when the belly starts becoming noticeable. At

that stage, when it’s still small. You actually feel as if you are

only overweight and you feel ugly. Now that I have a big belly,

I have no problems: if I pass before a mirror I see it.

Q – Have there been specific moments of great emotion

during the pregnancy, until now?

A – Some times I feel very sad; I don’t know if this is normal,

or connected to the pregnancy. For example I am more easily

upset and seem to feel things more intensely.

Q – Do you have specific fears?

A – I’m afraid the baby might have some problems, defects,

but it’s not a great fear; I’m actually convinced I will deliver a

beautiful girl. I don’t know why, but I’m convinced.

Q – Have you had dreams related to the pregnancy?

A – One dream I remember, because it was only a couple of

nights ago, I was losing blood from my mouth, I don’t know

why. In general when I dream I see myself pregnant, yes, I’m

always pregnant in my dreams now, even if I don’t

remember them clearly.

Q – When you realised there was a baby girl inside of you

what did you feel?

A – As I said before, a lot of amazement. And in this period, I

feel very creative. Alessandro said: “Of course, this is the most

creative of periods!” And I answered “Actually, if you think

about it, you and I have created a girl, created her from

scratch, because before there was nothing.”

(Zero)

Q – And the awareness of this new being came with her first

movements?

A – With the first movements, yes, but even more in this last

month. I really feel her, I feel she’s in here.

Q – What do you imagine her like?

A – Beautiful. I imagine her beautiful. And then obviously she

sleeps. She has to sleep for months. And then I imagine her

calm, friendly and always smiling.

Q – And physically?

A – I imagine her tall, skinny. And blond with blue eyes.

Simply beautiful.

Q – Would you say that there already is a relationship

between you and the baby?

A – I don’t know. I sing lullabies to her, inventing them. I talk

to her, simple things like “How are you?”. I talk to her in my

head more than with my voice. In the morning I tell her “Now I

will sing a lullaby for you, calm down”.

Q – Have you chosen a name?

A – Yes, we will call her Chiara. It’s not a family name, we

just chose it from the start. It’s nice, it’s a name we like.

Q – What do you think she will need in the first months?

A – Most of all love, lots of love, attention, in the first

months especially. She needs to feel in a warm

atmosphere, full of care, where she is taken care of,

welcomed.

Q – What kind of mother do you think you will be in the first

months?

A – In the first months I would like to be tolerant, open. I

hope to be very stimulating for the baby, and very caring.

Q – What kind of mother you don’t want to be?

A – I don’t want to be obsessive, anxious, authoritarian in

a bad sense.

Restricted/Disinvested

The restricted/disinvested representations emerge from

narratives in which a strong emotional control prevails, with

mechanisms of rationalisation towards the fact of becoming a

mother and towards the child: these women talk of their

pregnancy, of motherhood and of the child in poor terms,

without many references to emotional events and changes.

The storytelling has an impersonal quality, is frequently

abstract and does not communicate emotions or specific

images .

Restricted/Disinvested Mothers

Flaminia is a young woman who shows a restricted

representation of herself as a mother and of her

child. Even though she gives value to her

motherhood experience, Flaminia wants to maintain

her independence and self control and does not want

to be too conditioned by the child that is about to be

born.

Q – Would you tell me about your pregnancy?

A – I must say I was very lucky, I never had any problems.

Even in the first three months, I had no nausea, vomiting etc. I

did some things which you’re supposed to avoid, like skiing,

going on a motorcycle… but I felt ok, felt I could do it. But my

first three months were characterised by a certain

nervousness, a state of tension. After the first three months I

started getting used to the idea and calmed down. I still had

no physical problems. Then slowly, with great difficulty, I

started getting used to the idea of my body transforming.

Q – Why a baby in this moment of your life?

A – I thought about it a lot because I didn’t feel ready, even if

I’m not a kid anymore. I always had this idea I wouldn’t have

kids. I’m not crazy about kids, I’ve never been drawn to them

much. Then, maybe because you feel the need after a

number of years in a marriage, or maybe because my

husband who wasn’t convinced either, changed his mind… it

was a series of things which pushed me towards this

decision.

Q – What did you feel when you found out you were

pregnant?

A – I am quite cold, as a person. I don’t get carried away

easily, so even in this case I wouldn’t have told anyone, I’d

have kept it for myself. I first needed to get used to the idea.

Q – Have there been specific moments of great emotion

during the pregnancy, until now?

A – Maybe when I did the ultrasonography towards the fourth

month. That’s the first time you actually see this little growing

being and you see it whole. But mostly my feeling was a

reflection of the great emotion I could see on my husband’s

face. Seeing his reaction, I let myself be influenced by his

state of mind mood and felt it as if it were a feeling of mine.

Q – During the pregnancy, were there times when you felt

worried or mad about something? Have you ever felt any

particular needs?

A – I can’t think of anything now. The preoccupation

everyone has, on the baby’s health.

Q – Have you had dreams during the pregnancy?

A – Yes, but I never remember my dreams. I remember I was

eating yoghurt in the last one, but I have no idea what it might

mean.

Q – How do you imagine the baby?

A – I actually don’t imagine it.

Q – Do you imagine its physical features, its character?

A – No.

Q – And its sex?

A – Not even its sex, I didn’t want to know and I don’t want to

think about it. It will be a surprise.

Q – Do you and your husband talk to the baby or use nick

names?

A – Yes, but it’s mostly my husband who talks to it, not me.

Even if I feel there is a bond between the baby and me, I

still can’t bring myself to talk to it.

Not integrated/Ambivalent

The not integrated/ambivalent maternal representations

are those found in confused narrations, characterised by

digressions and by the woman’s difficulty in answering

questions in a clear and articulate way. The coherence of the

story is poor, and an ambivalent involvement of the mother

towards the experience she is living, towards her partner and

towards her family is present. These women often express

contrasting attitudes towards their motherhood, or towards the

child. The son or daughter is frequently awaited to satisfy the

caregiver’s needs.

Not Integrated/Ambivalent Mothers

Roberta is an example of Not Integrated Mother. A young

woman of twenty-nine years old, the idea of having a child has

made its way in her amidst many ambivalences and

uncertainties, showing all the difficulties that a not integrated

mother manifests in fully accepting a maternal identity.

Q – Would you tell me about your pregnancy?

A – In the beginning we had many things, those egoistic

projects of settling everything first, because we started out

with nothing, and we thought ‘we’ll think about a baby later

on. So let’s say it wasn’t a thought, like we both had of

the baby in the beginning. Then when things started

working out, everything, we looked each other in the eye

and said ‘what do you think about it? I am thirty already’.

And he didn’t want to, he had decided that he was already

old when we married; he had already settled, so he had

some difficulties, he said he didn’t want to be a

grandfather. (…) He had these problems, fears, which I

didn’t have, mine were completely different, like how will I

help my child in 20 years time, finding a job, or school for

example.

Now I’m completely terrified on how to do things, and the

kinder garden, the people he will hang out with cause we

know what it’s like, and my mentality is not ‘live by the day’,

maybe I worry too much about everything around me.

That’s why I used to say ‘let’s wait’ then one fine day this

decision just arrived. ‘What do you think about it?’ ‘And maybe

yes, it’s time’, we made a joke about it, ‘Time to take on

responsibilities...’ That’s when I started thinking, I started

asking around, how many children, how long did it take etc.

Someone told me ‘I thought about having the first one for four

years and then the second in twenty day’; others go:

‘Immediately, one after the other’. These kind of things. I said

‘O God, I waited so long, and now I’m thirty’, in fact this was

my fear, I said ‘You’ll see that now that I want one, it won’t

come’.

(…)

I looked for a laboratory where they could do my, my urine

test and so I did it, and she goes ‘Congratulations’ and I was

practically walking trying to avoid holes, absurd, because I

had taken two buses to get there, and I was walking as if over

boxes of eggs, I was afraid of ruining this thing.

I thought ‘Oh my God maybe I did something in the first days.

(…)

In the beginning, after a month and a half, I started having

nausea problems, upset stomach, lots of saliva, so that after

two months I was thinking ‘Why on earth did I do it?’.

Because I was really sick. (…) I was thinking ‘What a terrible

pregnancy I’m going to have’ because some would say ‘It’s all

going to end soon’ and others ‘I threw up all the way to the

ninth month’.

(…)

And my doctor said ‘it’s mostly psychological’. On one hand

we wanted it, but on the other maybe there was a part of

truth, because I was very embarrassed to tell my boss, I

didn’t know how to tell him.

Q – How did you feel when you found out you were

pregnant?

A – I found out after only a week, and there I was, telling the

nurse ‘Are you really sure?’, because maybe it could be like

with those pharmacy tests, which are uncertain. They told

me in the pharmacy that if it’s sure, when it appears clearly

it’s positive, that is, it’s negative; no, no it’s positive, when it

appears clearly; when it’s uncertain it could be positive or

negative. I was so excited because it’s not… I was saying

‘No, it’s not possible’, in that moment it wasn’t ready. (…)

In the laboratory, he said “Look, the stick doesn’t become

pink if it’s not positive”; so nothing, this thing was pink,

‘if you say so it must be, you guarantee, when I walk

out of here I can tell my husband’.

Q – How did you feel and how did your life change during

pregnancy?

A – How did I feel? Happy, really happy personally, and all

the people around me where happy, so it was really nice;

except for my boss, maybe, because probably for him it

wasn’t. But aside from that, even with the people we know, I

found people very happy to give me some advice, things like

don’t do this, or that. Don’t gain too much wait or eat all you

can cause it’s for the baby, everyone. Younger people will

say ‘Don’t eat too much, you’ll get fat’ and older people will

say ‘Eat a lot so you have a big healthy baby’, clearly not.

Q – Have there been specific moments of great emotion

during the pregnancy?

A – Yes, when I did my ultrasonography in the fourth month,

when they said ‘this is the heart beating’ and on the screen

monitor there was this confused image, but when we saw the

head, I absolutely didn’t imagine that I could see a profile. It

really gave me a strange impression, seeing it.

(…)

Then there’s this thing which doesn’t excite me but amuses

me. I have found out that, in the morning, drinking very hot

milk, the baby does some strange movements. And I feel them

even when I drink cold water, directly out of the fridge; so

sometimes I switch from a hot thing to a cold thing to see what

reactions it has.

Q – Are there dreams you remember of this pregnancy

period?

A – Yes, I realise I have been dreaming more, but mostly it’s

bad dreams. Sometimes sad dreams, sometimes bad ones,

really bad.

Q – What did you feel when you first realised there was a

baby inside you, ?

A – Happy, because I thought ‘it’s there, so I have to be

careful of what I do, to do things to not… The first period for

example I was very anxious and I had terrible pains in the

stomach and I was afraid the baby felt pain too.

Q – How do you imagine this baby?

A – Wishing is different from imagining. How I imagine it, I

don’t know, I imagine the baby ugly and dark, with dark hair;

how I wish it to be instead is different, obviously beautiful and

with clear eyes, beautiful; well, I’d like one thing, one wish,

that it doesn’t look like me.

Q – Do you imagine the baby as a boy or a girl?

A – I imagine it as a boy but I hope it’s a girl.

Two independent, trained, certified, and reliable judges code

IRMAG interviews according to the above described seven

rating scales. Inter-rater reliability for IRMAG scales ranged

from .89 (coherence) to .96 (predominance of fantasies ),

with a mean reliability of .92. Inter-rater reliability with

respect to the main category was 94% (k=.83, p<.001).

Disagreement was solved by a third rater.

Statistical validity is supported by an exploratory factor

analysis using oblimin rotation, performed both for

maternal representation of herself as a mother and of

her child.

Considering the statistical characteristics of the Interview the

screen plot suggested that two factors should be extracted,

in both cases. The two dimensions formulated to define the

construct of mother's mental representations of herself as a

mother were confirmed by factor analysis and accounted for

70.50% of the post-rotational variance. Measures of internal

consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) were conducted to examine

the reliability of the two dimensions (F1, M=2.99, SD .40, α

.85; F2, M=2.61, SD .58, α .52 ).

In the same manner, the two dimensions formulated to define

the construct of the mother's mental representations of her

unborn infant were confirmed by factor analysis and

accounted for 78.95% of the post-rotational variance.

Measures of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) were

conducted to examine the reliability of the two dimensions

((F1, M=2.89, SD .40, α .93; F2, M=2.63, SD .73, α .45 ).

At the end of the interview the are 5 scales modelled on

semantic differentials, each containing 17 pairs of opposite

adjectives. The first three scales designate the individual

characteristics of the unborn infant, of the woman’s self and

of the infant’s father. Comparing the three lists, it is possible

to evaluate if the representation of the baby is more

influenced by the woman’s self-representation or that of her

partner.

The other two scales, deal with the maternal characteristics

of the pregnant woman and those of her mother. In this

case adjectives will refer to affective orientations, personal

lay-out, maternal role, maternal sensitivity and competence.

The interview is used to assess how information and

emotions concerning the woman herself and her child are

organized, whereas the five scales give us a picture of the

contents of the representations. The two instruments can be

used together (Ammaniti et al. 1992; Ilicali, Fisek, 2004)

and independently (Ammaniti, Tambelli, Perucchini, 1998;

Pajulo et al. 2001; 2006).

To explore the configuration of paternal representations and

their differences from the mother’s the I.R.PA.G. (Interview

for Paternal Representations during Pregnancy-Ammaniti,

Tambelli, Odorisio 2006) is used.

As indicated in table 1, fathers’ representations have a

different distribution confronted with mothers’ ones.

Tab. 1 Distribution of Maternal and Paternal Representations

during Pregnancy (IRMAG/IRPAG)

Group

Integrated

Ambivalent

Restricted

Mothers

(N=162)

89 (54,9%) 35 (21,6%)

38 (23,5%)

Fathers

(N=162)

93 (57,4%) 15 (9,2%)

54 (33,4%)

• hi2(2, N=324)= 10,87 g.di l.=2 p= 0.004.

The results reported in tab 1 show that in our sample the

integrated/balanced parental representation is equally

distributed among women and men, as opposed to the

restricted/disinvested one more common among men and

the non integrated/ambivalent one more common among

women. These data confirm the differences of

psychological orientation of mothers and fathers during

pregnancy, even though the mothers’ and fathers’ attitudes

draw closer after birth.

The use of IRMAG-R in at-risk pregnancies allows to study

the contents and structure of maternal representations

which give significant indication to evaluate parenting

capabilities during pregnancy and the postnatal period.

Tab. 2 Distribution of Maternal Representations during

pregnancy in risk and non-risk mothers

Group

Integrated

Ambivalent

Restricted

Normal

mothers

(N=239)

60,7%

(145)

20,1% (48)

19,2% (46)

Risk

mothers

(N=132)

43,2% (57) 34,1% (45) 22,7% (30)

• hi2(2, N=371)= 11,93 g.di l.=2

p< 0.003.

In at-risk situations, persistent preoccupations and phobic

fears have been found; a specific scale is being created for

these. This scale allows us to detect the levels of

pervasiveness and intrusiveness of fears in relation to the

pregnancy, to delivery and to the rearing of the child. The

scale for the evaluation of the risk factors is, like the others,

an ordinal scale with a five point range.

The IRMAG-R can be used for research in the clinical field

to study the psychological state of women during pregnancy

or for at-risk situations, in medically assisted pregnancies or

in projects to support motherhood.

2) Self-Report Questionnaires and Scales have been used

to assess attachment processes during pregnancy, when

emotional ties start rising between mother and child. The

construct of prenatal attachment (Cranley, 1981; Condon,

1993; Muller, 1993) takes account of the mother’s affective

investment for the foetus, which is “the most precocious and

basic form of human intimacy” (Condon & Corkindale, 1997,

1998). Condon (1993) has suggested a hierarchical model

of attachment based on five subjective experiences which

derive from maternal love experience and mediate this core

experience and overt behaviours. These subjective

experiences are expressed in maternal disposition "to know"

the loved foetus, "to be with" him or her, "to avoid separation

or loss" of the loved object, disposition "to protect" the

foetus and finally "to gratify" the foetus's needs.

The quality and evolution of the prenatal attachment is

influenced by many factors, first of all by the advancing of the

pregnancy which entails growing ties between the mother

and child, hastened by the appearance of foetal movements.

Aside these factors, the personal history of the woman and of

the couple have a significant influence on prenatal

attachment.

Obviously this attachment is not only present in mothers but

in fathers as well, although in 15-20% of the fathers this

affective attachment to the foetus seems not to rise

(Condon,1993).

The instruments more frequently used to study prenatal

attachment are Self-Report Questionaires.

Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale (MFAS) (Cranley, 1981),

based on 24 items upon which an agreement score from a

range of 5 points is expressed. Higher the score in the items

and more definite and consistent is the mother’s attachment

to the foetus. The items refer to 5 basic components:

differentiation of self from foetus, interaction with foetus,

attributing characteristics to the foetus, giving of self, role

taking. Measurements of internal consistency (Cronbach’s

alpha .85) are good on the total of the items, while the

subscales have lower scores (between 52 and 73). Typical

of the MFAS is that the items evaluate the mother’s

behaviour more than her feelings or thoughts. In the

validation sample used by Cranley, this instrument was used

between the 35th and 40th week. The scale of maternal

attachment was later adapted to a specular version which

measures the father’s attachment to the foetus.

Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) (Condon,

1993), based on 19 items, the response is rated on a 5

response options, enquiring as to the frequency and /or

intensity of these experiences over the preceding 2 weeks.

The scale was used during the third trimester of pregnancy

and has good levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s

alpha >.80).

It measures, beside a global attachment value, two

underlying dimensions: quality of involvement and intensity

of preoccupation. From the characteristics of these two

factors, four styles of attachment can be identified: positivepreoccupied, positive-disinterested, negative-preoccupied,

negative-disinterested. The fathers’ version is based on 16

items, 14 of which are in common with the mother’s, as

Condon sustains that prenatal attachment, even though it has

a common basis for mothers and fathers, has specific

aspects as well.

Prenatal Attachment Inventory (PAI) (Muller, 1993). The

inventory is based on 21 items. The response to each item is

rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The higher score indicates

greater attachment. In structure it is similar to Cranley’s scale

but the aspects explored are different. It refers to attachment

theory, describing women’s thoughts, feelings and relationship

towards the foetus. Two constructs, in particular, are

extremely relevant in the theoretic model at the basis of the

PAI: attachment relation to the partner and adaptation to

pregnancy, because according to Muller (1993) these are both

positively related to prenatal attachment. The statistical

analyses have shown good validity and internal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha varies from 81 to 91 in all researches that

used it). Muller’s instrument does not allow an evaluation of

father’s prenatal attachment.

The measurements from the self-evaluation scales

described above concern the quality and quantity of the

emotional investment of the parents towards the foetus

without, however, going into more complex elements

(mental representations of the parents, parents’

attachment models). Therefore these scales can be used

together with other research instruments.

3) Inventories have been used to study the psychic state

during pregnancy, such as the primary maternal

preoccupation, a mental state Winnicott (1956) described as

“almost an illness” that a mother must experience and

recover in order to create and sustain an environment that

can meet the physical and psychobiological needs of her

infant. He hypothesised that this special state begins towards

the end of the pregnancy and continues through the first

months of the infant’s life.

If Winnicott’s concept had a clinical sense, it was later

explored by means of a semi-structured interview, Yale

Inventory of Parental Thoughts and Action,YIPTA

(Leckman et al., 1999) within which an Inventory

systematically explores the mother’s and father’s

preoccupations and thoughts.

The specific content of the YIPTA covered the thoughts and

actions associated with three domains of caregiving (Care),

relationship building (Relationship) and anxious intrusive

thoughts and harm avoidant behaviours

experienced/performed by parents (AITHAB).

The YIPTA is designed for the use of experienced clinicians

and has been used at the eighth months of gestation, at two

weeks after delivery and three months after birth.

The measurements of the Early Parental Preoccupations and

Behaviours, besides outlining the psychic states typical of

mothers, highlight depression and anxiety symptoms that can

appear during pregnancy, while the AITHAB measurements

highlight intrusive thoughts and harm avoidant behaviours

which are conceptually related to obsessive-compulsive

disorders (OCD). It can be hypothesised that some forms of

OCD that appear in this period are the dysregulative result of

this specific psychic state that appears during pregnancy.

Both parents present the highest levels of “preoccupation”

towards their child around birth time (between the eighth

month of pregnancy and the second week after delivery).

Thoughts about the baby during the period of Winnicott’s

primary maternal preoccupation occupy the minds of the

mothers and fathers for respectively 14 and 7 hours a day.

At the eighth month of pregnancy (Leckman et al., 1999) the

following has been found: preoccupations on the baby’s

health in 95% of the mothers and 80% of the fathers (health,

growth, aspect), thoughts of damaging the baby in 37% of

the parents (making it cry, shaking or hitting it, dropping it).

These thoughts are a reason of personal distress in 20% of

the cases.

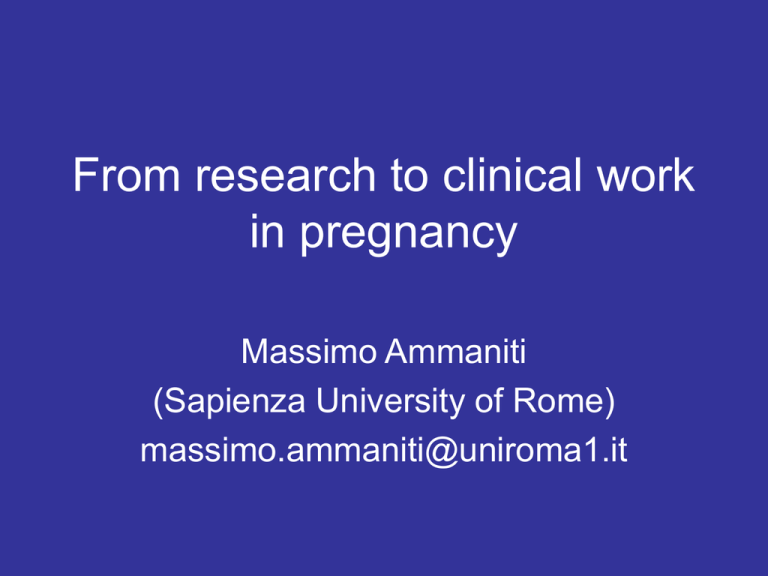

The progress of thoughts and preoccupations shows that

these tend to appear around the eighth month of pregnancy

and reach their climax around the second month after birth

to then slowly disappear. (fig.1).

The YIPTA permits an evaluation of the level of parental

preoccupation which is an important psychic state during

pregnancy and the postnatal period because it focuses the

parents’ attention on the baby’s health and stimulates

better caregiving capabilities. In the mother’s depression

and in obsessive-compulsive states the level of

preoccupations can occupy the mother’s mind completely

and interfere with her maternal capabilities.

Intensity of

preoccupations for the

child

Figure 1

Trend of parental preoccupation during pregnancy and

post-natal period

(From Leckman et al.,1999 modified)

Mothers

Fathers

8th month

1st month af ter birth

2nd month

3rd month

Clinical implications

• Desire of motherhood and of pregnancy (Pines, 1972).

This element has important implications for adolescent

pregnancies, in which a narcissistic attitude is in the

foreground.

To this purpose it is important to notice how the news of the

pregnancy was received and how it was (or wasn’t)

communicated to the family.

• The pregnancy takes on a different meaning depending on

the personal history of the woman, on her experience of

attachment as a child, on her adolescence dynamics, on her

relationship within the couple and especially of her

relationship with her mother.

Our research (Ammaniti et al., 1995) has outlined three

different

maternal

styles

(integrated/balanced,

restricted/disinvested,

preoccupied/ambivalent)

that

correspond to observations in the clinical field (Raphael-Leff,

1993) which have drawn attention to different configurations:

facilitator, regulator and reciprocator mothers.

Our researches point out that these psychic maternal

configurations do not overlap with attachment models which

on the contrary are relatively stable. These maternal

configurations are influenced by pregnancy psychological

dynamics, that is by the maternal constellation (Stern, 1995)

within which a motivational system based on caregiving and

on the child’s protection is activated. As stated by Stern, the

pregnant woman tends to rely on other women who have had

children and have gone through the motherhood experience.

• From this point of view, the relationship with one’s own

mother represents the most significant relational area

because a woman facing pregnancy is undergoing a great

transformation: from woman she is becoming a mother, and

this is possible only if she is authorised and sustained by her

mother, who is her identification model.

In clinical situations, this relationship can become particularly

conflicting, as a competitive dynamics of depreciation is

established and feelings of jealousy, envy and refusal are

cast upon the mother figure.

Often in pregnancy, the woman has a tendency to idealise

her maternal capabilities and to defensively depreciate her

own mother; regarding this, the birth of a child can help the

elaboration of the ambivalence and stimulate a more

adequate identification with one’s own mother.

• An important area is the woman’s representation of the

child she bears. In most cases, the child is given personal

features, a nickname, he is attributed intentions, motives and

can even be considered a partner for conversations.

In other situations, in the detached mothers for example, the

child is considered a foetus, not a person yet and is not

represented with personal features and characteristics.

In at-risk situations, the child can be perceived as a danger, a

threat for the mother’s autonomy, a dependent presence,

even a parasite (Ferenczi, 1941).

• Regarding the area of preoccupations and fears, these can

appear during the last phases of pregnancy which are

directed to a psychological focusing on the child (primary

maternal preoccupation, Winnicott, 1956).

However, it is in this phase that psychopathological shifting

towards obsessive-compulsive disorders can reactivate or

appears for the first time.

In the primary maternal preoccupation, the persistent ideas

are similar to obsessive ideas, so is the avoidance of certain

ideas such as hurting the baby and the need to verify

everything is ok. The substantial difference is that these

preoccupations are egosyntonic while obsessive ideas are

egodystonic.

• Considering the psychopathological risk in pregnancy,

depression represents a frequent condition (10%

O’Hara,1997) which can have important consequences on

the course of the pregnancy, of the delivery and on the

mother-child interactions after birth.

Therapeutic implications

• Pregnancy is a particularly fertile phase for

psychological work: the woman has a more accentuated

introspective orientation and there is more permeability

between the unconscious and conscious spheres,

which is demonstrated by richness of dreams.

Even open-eye and subconscious fantasies occupy

great space and are centred on the child and on her

own maternal function.

• Therefore it is a privileged time for working with women

on the maternal constellation centred on her role as a

mother, on her child and on her relationship with her own

mother. This work can have a preventive function in view

of the postnatal period and at the same time a therapeutic

function, especially in at-risk situations.

• A few words on the women who were in psychotherapy

before their pregnancy: in this case the other motivational

systems which where in the foreground earlier now tend to

become marginal in the woman’s life and in the therapeutic

space; the maternal constellation area becomes more and

more central, and within it conflicts of the past with the parent

figures can reactivate.

In this phase, the future mother’s psychic world is embodied

with the physical experience of transformation caused by the

pregnancy and the growing presence of the child.